FUNNYBONE DHARMA

Not only is the visual design of the Winter 1991 issue of Tricycle very pleasing, but the subject matter is diverse and provocative, a veritable feast of paradox.

We are told by Khyentse Rinpoche on page 41 that “To cut through the mind’s clinging, it is important to understand that all appearances are void, like the appearance of water in a mirage.” And then, in Rick Fields’ piece, we are reminded by Bodhidharma that “one who thinks only that everything is void is ignorant of the law of causation.”

Trungpa Rinpoche is quoted, as if from beyond the stupa, saying, “On the whole, discipline and practice are essential whether I am there or not.” But the Krishnamurti “expose” on page 65 states that “Helping others to find their way in a pathless land became Krishnamurti’s avowed mission for the next seven decades.” This sentence refers to Krishnamurti’s famous statement made in 1929 when he dissolved the Order of the Star, saying that “Truth is a pathless land.” A good part of his message is that institutionalized spiritual practice and discipline has little to do with realization.

Raising the ante on this celebration a bit further is the well-known fact that Trungpa Rinpoche’s varied sex life and passion for alcohol were in plain view of his students. On the contrary, the alleged exercise of Krishnamurti’s sexuality is now said to have been hidden from the view of his (non) students.

Which teacher hurt or helped his followers more? Is sexual and alcoholic excess better or worse in demonstrating truth than strict celibacy and sobriety? What are the realities in between? These are interesting and humorous questions to me. They are funny because they point to the inherently mysterious and foible-laden aspects of the human enterprise. No matter how we manifest, radically like Trungpa or conservatively like Krishnamurti, our human vulnerability is still our greatest gift. After a point, you just chuckle a bit and find your own way.

For Buddhist spirituality to find its place on this continent, it needs to laugh at itself a little more, and to moderate its excessively cerebral bent, which tends to deny friendliness and emotional realities. The Third Noble Truth is connected to the funnybone, and to the heart as well.

RICHARD SIMONELLI

Boulder, Colorado

KRISHNAMURTI CONFLICT

Krishnamurti was one of the greatest, perhaps the greatest spiritual master of the 20th century, because of his teachings, not because of his image. For many he has indicated the direction to liberation. He is the finger pointing to the moon, not the guru taking the responsibility of bringing you to that moon if you surrender to him. Your interviewee considers that Krishnamurti’s guidance is like that of a stock advisor. It is also like that of the Buddha.

Those who take Krishnamurti as guide on the spiritual path do so because they recognize in his teachings a part of their own experience. Krishnamurti’s words clarify what we deeply perceive as true. His teachings are valid because they are grounded in our own experience, not because of Krishnamurti’s enlightenment experiences, his celibacy, or his fairness to D. Rajagopal. To question these features of the Krishnamurti image may be good gossip but spiritually irrelevant, just as discussions about the homosexuality of Tchaikovsky or the anti-Semitism of Wagner are musically irrelevant.

When I subscribed to Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, I did not expect gossip. What is the relevance of this piece, apart from pretending to afford us a glimpse into the bedroom of a celebrity?

JACQUES MAQUET

Los Angeles, California

Exceedingly puzzling is the stance you took in your interview with Radha Rajagopal Sloss regarding her book, Lives in the Shadow with J. Krishnamurti. Even the title of your interview, “The Shadow Side of Krishnamurti,” implies that you have accepted the embittered Rajagopal family’s allegations as fact, an impression strengthened by several statements you make within the article itself, such as “Radha Sloss’ mother was Krishnamurti’s clandestine lover for some twenty-five years.”

Sloss’ book is rife with distortions and negations of facts that are simple matters of court record. This leaves readers in the position of assuming that Tricycle approached this great glob of gossip with an even greater dollop of prejudice. Is it because Sloss is interested in Buddhism? Is it because Krishnamurti made short shrift of path-following?

GALADRIEL FROND NAIR

Miami, Florida

I have always considered it a privilege to have met J. Krishnamurti several times at Ojai, and to have met both Mr. and Mrs. Rajagopal at the same time. Your interview with Mrs. Radha Sloss has changed more than just my regard for Krishnamurti; it has changed some of my oldest friendships as well. When I first read the interview I blamed your magazine for sensationalism, and your interviewer for being biased. I found Mrs. Sloss naive and defensive. Then I decided that Mrs. Sloss’ report simply wasn’t true.

In the spirit of common sympathies, I telephoned friends across the country who have for many years been in, or associated with, Krishnamurti’s “inner circle.” I am sorry to say their response was as disheartening as the interview itself. I heard an earful about complicated legal entanglements and how embittered all the Rajagopals had become in the wake of Krishnamurti’s abandonment. In three instances, when I asked about the love affair between Krishnamurti and Rosalind, I was told, “Oh, that’s not news, everybody knew about that.” And: “Well, that’s not important. It has nothing to do with his enlightenment.”

This turning of the tables made me feel caught in a web of insanity. Krishnamurti’s purity had always been beyond question. For years I had been told by people who had lived at Ojai that he was “a virgin.” His celibacy and the implication of detachment from ordinary human needs was communicated at every possible occasion in order to enhance the credibility of his enlightenment. There may not be a relationship between one’s sexuality and enlightenment. There may not be a relationship between absolute understanding and relative integrity. It is not for me to discuss these matters. But if Krishnamurti’s sexuality did not diminish his enlightenment, why was it deliberately kept secret? In the face of public disclosure, what I heard—and was quite ready to participate in—was an attempt to deflect the main concern by discrediting Mrs. Sloss and her parents. Sadly, by blaming the Rajagopal family, these beleaguered defenders of the faith are still trying to manipulate false images, which, it seems to me, is foremost among the many disturbing factors in this situation.

I am asking that my identity be withheld because I do not wish to further rupture private friendships, and certainly not in public. At the end of a life, long friendships mean the world. But to think we spend our lives so caught in our delusions makes me sadder than I can say. Thank you for publishing this interview.

NAME AND ADDRESS

WITHHELD UPON REQUEST

I have read Krishnamurti, Trungpa, Merton, etc., ad nauseam, for decades, and would like to share briefly a few observations pertinent to myself, in light of the interview with Radha Sloss. To be a whole person seems to be the point of being alive after all. Light and dark, wiseman and fool, all cramped up in one body; what an incredible opportunity! This humanness must surely have been a struggle for Krishnamurti as for others. I’m not surprised that he indulged in an affair of the heart. Living lives seems conducive to stone throwing and gossip and error—then forgiveness, atonement, and laughter.

JULE ANNE BOOTH

Portland, Oregon

FROM THE OLD COUNTRY

I enjoyed the second issue of Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. It gave me a broad perspective on Buddhism in America. Many of the items that I read disheartened me but other items gave me more hope. Those of us who are Buddhists from the old country—in my case, Nepal—have yet to understand in a more detailed fashion the types of Buddhism practiced in the United States.

ASHOK BAJRACMARYA

Hastings-on-Hudson, New York

POST CONSCIOUSNESS

First of all, thank you for such a great publication! Couldn’t you please consider going monthly?

I would also like to address Jon Tessler’s letter (from Seal Beach, CA). As a U.S. Postal worker, our carriers do not use magazines as coasters. I feel extremely sorry for our customers when magazines arrive with torn covers and missing labels. I love magazines and books and treat them with respect. Besides, they are someone else’s property.

BEVERLY L. DEMPEWOLF

New Milford, New Jersey

CALIFORNIA SURF

Thank you for the courage to publish Rick Fields’s “The Changing of the Guard” and “The Shadow Side of Krishnamurti.” If a vigorous American Buddhism is to emerge from the Tibetan, Japanese, and Burmese imports, we need to know what spiritual practices work for us. It now appears that after 20 years of mahamudra, shikan-taza, vipassana, and zazen, some wonderful talks have been given and some nice books written, but what of transformation? The sexual energy is still just in the lower body.

Maybe mantra-shakti practices would be more effective for the evolutionary transformation of Americans. There has always been many ways of dealing with finding oneself in an ocean of suffering. You can call on the Lord for help, you can try to calm the waves, you can try to get to the other shore, or you can learn to surf. Every one must make his or her own choice. I’m paddling out—surf’s up!

CASEY COLEMAN

San Diego, California

INCEST & INQUIRY

Thank you for including Dr. Shainberg’s comments on the harmful effects of incestuous relationships after the Brother David and Aitken Roshi exchange. Spiritual growth involves freedom from social conditioning but such freedom can breed abusiveness, even criminality, if not contained by moral standards. Moral standards are to some extent culturally specific, and the traditional Buddhist precepts hold little interest for many Western practitioners. Westerners attracted to Buddhism tend to be products of the sixties’ counterculture, which, by definition, questioned established social structures and traditional values. Consequently, many Western Buddhists lack an established system of ethics (Western or Eastern) that could protect them during their spiritual explorations. The establishment of social ethics appropriate for Western Buddhism is an important project; I am looking forward to Tricycle‘s continued contribution to this difficult dialogue.

R. KARL HANSON M.D

Ottawa, Ontario

Brother David responds:

It doesn’t come as a surprise to me that some of your readers were troubled by my asking, “What is wrong with incest?” And I am grateful to Dr. Hanson for voicing his uneasiness with my question. Many of us have been reprimanded, looked at askance, or even ostracized for asking questions, as if asking a question were an attack on the truth. Is it not rather the only means for getting at the truth? Unless we “raise” a question, it will sink down on us and might well submerge us, in the end.

If we ask “What is wrong with incest?” the question forces us to clarify, first of all, what we mean by incest. Can we be sure that it means the same to everyone who uses this term? If not, how can we be sure that everything labeled with this invective is truly reprehensible? We breathe the charged atmosphere of a child-abuse frenzy unleashed and exploited by the media. In this atmosphere, terms like incest and molestationhave become threatening to relatives, friends, and teachers alike. Many have become afraid of even touching children lovingly for fear that this will be misinterpreted. Confused by the publicity, even children may feel “abused” when touched.

Though sensationalized by the media, child abuse, along with many other forms of abuse, simply reflects the violence in our society. To be concerned with incest—which is only one of the many forms of abuse in this society—is not getting at the root of what’s wrong. And the question

“What’s wrong with incest?” might lead thinking persons to go on to more basic questions, such as “What’s wrong with our society?” and “Why are we so violent?”

But my main concern here is not with that topic but with the necessity of asking questions. Socrates got us off to a good start. Without his questioning we might never have awakened to philosophical inquiry. He paid a high price though for asking questions: the authorities made him drink the cup of hemlock. Jesus gave to the raising of questions religious status: “Why do you not of yourselves judge what is right?” (Luke 12:57), he asks us. Why do you not question authority? He, too, had to pay a high price for encouraging questioning: the authorities had him crucified.

Jesus raised radical questions and encouraged radical questioning among his followers. This fact provides common ground for Buddhist and Christians; for, the Buddha, like Jesus, appealed to the authority of his hearers’ own experience. Christians, like Buddhists, are to be guided by inner authority. Authoritarians within the Christian churches may make it difficult to see this clearly. The issue is further obscured by Christians who actually prefer to let external authorities lay down the law for them; it’s easier than taking responsibility for one’s life.

In society as a whole, most people allow themselves to be unthinkingly guided by the authority of public opinion. Few dare to question that authority. When I insist on my right and duty to raise questions, I do so as a follower of Jesus and a brother of Buddhists. Together we must explore issues of social ethics, precisely by questioning authority—radically and respectfully.

DAVID STEINDL-RAST

IMMACULATE HEART HERMITAGE

Big Sur, California

I read with great respect the insights of Aitken Roshi, Brother David Steindl-Rast, and Dr. Diane Shainberg. The endlessly fascinating aspect of being human is that no one of us may experience everything or have all of the perspectives necessary to have the final word on any issue. Each time I reread the article, the feeling grows stronger that I must respond with my own perspective on the question of sexual relations between a teacher (guru) and student (chela) for the benefit of others who have become involved in such relationships or find themselves with the opportunity to become involved.

When I first met my teacher, I did not know he was a teacher. This awareness grew slowly over many months of conversation and friendship.

Little by little he accepted and guided me; and I came to rely on him more and more. He never preached, or demanded anything of me, or insisted on a point of view. In face-to-face contacts he said little of the esoteric and much of the everyday.

It was months after I had discovered through my readings about the sacred kundalini energy that he admitted he had the knowledge and power to give kundalini initiation. It was months after this that he finally consented to offer me this initiation. When he knew I wanted to participate in and accept this transforming process, was totally sincere, and had undergone months of purification, he began his own preparations to give the initiation.

Perhaps others of your readers are familiar with the life of Yeshe Tsogyal, the great dakini who received her initiation from Padma Sambhava in this way. Many other great female gurus and male gurus have lived in this tradition, yet it is a little-known path. As a whole, I have found that little is discussed or known about the path and practice of women in the Buddhist tradition.

There were times when I experienced many of the emotions described by Dr. Shainberg.

Perhaps the problem for women who get stuck in their pain and negativity about spiritual sexuality lies in their perception of themselves and their partners. Women typically hope to be taken care of, to assume a dependent role, to be rewarded for “granting their favors.” These attitudes have no place in a spiritually transforming sexual relationship. Such a relationship is a growth experience through which a person learns his or her true nature and assumes the authority that comes with knowledge.

The gift of power (energy) exchanged or given during the initiation is a precious gift. What transpires on the spiritual plane cannot be assumed to define a relationship on the physical, human plane. In other words, a sexual relationship with a spiritual teacher does not carry with it the usual human relationship defined by fidelity, companionship, gifts, and so on. The point of such a relationship, in fact, is for the student to eventually come to know reality—that she and the teacher are the same. Dependency is to be discouraged. Interdependency is the usual goal of secular sexual relationships.

This is the first time I’ve needed three Tricycles: one to underline and use for daily practice, one to keep intact for my library, and the last to undo for beautiful portraits and art work for meditation. (Your premier edition cover picture of the Dalai Lama sits on my shrine.)

My experience is this: The clear and compassionate portrayals of the shadow aspect of master-student relationship heal by the very acknowledgement and recognition of the complex nature of the powerful and potentially liberating partnership. It sparks dialogue that awakens and releases.

Bless you for your caring and impeccable communication.

DOMINIE ANNE CAPPADONNA

Kamuela, Hawaii

DO THE RIGHT THING

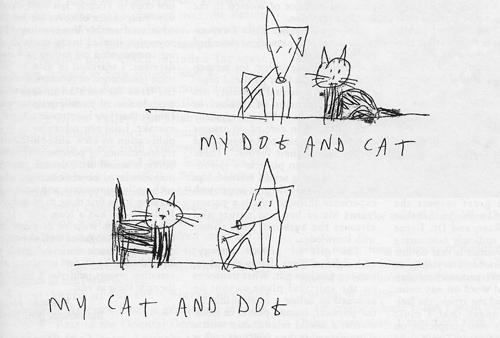

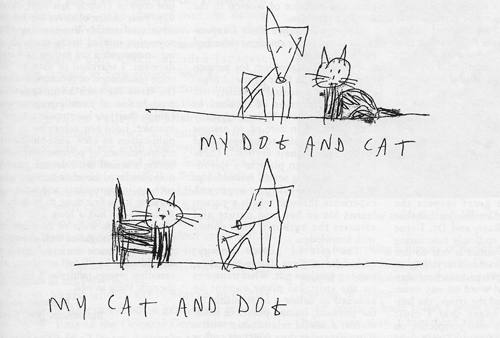

I was appalled when I received my first copy of Tricycle last week (Vol 1, #2). Your choice of cover art for this issue was terribly unappealing. The voyeurism implied in the crude drawing compounded my feeling of bewilderment. I searched in vain to find some justification or connection within the issue for such an unappealing reproduction of juvenile pornography. I think that you have made a terrible mistake. I did not subscribe to your publication to view unsophisticated representations of persons interrupted during a sexual act. I cannot pass the magazine on to friend or stranger when such an inappropriate and unsavory drawing is the first thing to be noticed. Buddhist art has a long and varied history. If you want to decorate the cover of your magazine with something that will “catch the eye,” look to Buddhist art. You’ll find intriguing and arresting images, and you’ll be doing the right thing as well.

BRENDAN HEALY

Bloomfield, New Jersey

HONORARY CITIZEN

I love your magazine! The warmth, the wit, the depth, the design, the searing commitment to viveka! I am a long-term student of yoga and its philosophical systems. Reading Tricycle though, I wonder if I might apply for honorary citizenship in the American Buddhist community!!! I am proud to be a charter subscriber and wish Tricycle and its creative team a long and joyous life.

SUZIN GREEN

Washington Depot, Connecticut

ATTACHED IN THE DHARMA

Buddhism is supposed to diminish our attachments, but your new magazine has (happily) given me one more. The Winter 1991 issue is my first acquaintance with Tricycle; how strange, then, that it already seems an old friend. Everything about it seems so right, so in place! As a Buddhist who has been out of touch with the Buddhist scene (but not with the dharma) for two decades, it was like a homecoming: so many of the names were familiar to me, and some I have known personally. Once more I feel part of the sangha.

DAVID LUKASHOK

Niteroi, RJ, Brazil

DUHKHA DIALOGUE

Robert Aitken’s brief discussion of the term suffering is very helpful. I have long been puzzled by the teaching that suffering is something we can overcome. Suffering seems too intrinsic to humanness to be dispensed with entirely. Aitken proposes the word anguish instead of suffering; in my view, a more appropriate word would be fear. It is fear that comprises the alchemy whereby suffering and anguish both become agents of transformation and growth. “Perfect faith casts out all fear,” said Saint Paul. I think he was talking about enlightenment. Another alternative worth considering is oppression, understood as a state in which the soul, or mind, is gripped by fear. (Sound familiar?)

M. AMOS CLIFFORD

Visalia, California

Regarding Robert Aitken’s discussion of dukkha, “anguish” certainly seems preferable to suffering. Anguish has a hearty, human feel. Personally, I prefer to place impermanence at the center of Buddhism. I believe it is unfortunate that so many texts introduce Buddhism with “life is suffering.” No wonder it is often branded as pessimistic.

DANIEL DEFoE

Morgantown, West Virginia

In reply to Robert Aitken’s discussion of the word dukkha and its translation: The most interesting etymology of this word that I have encountered is from an essay, “Living with Dukkha,” by Mokusen Miyuki (Buddhism and Jungian Psychology, Falcon Press, 1985). Miyuki refers to the Sanskrit roots of the word. “Etymologically dukkha is composed of the prefix jur (‘bad’) and the root kha (‘the hole in the nave of a wheel through which the axis runs’).” Miyuki goes on from this to suggest “dis-ease” as a better translation. I don’t think “dis-ease” quite hits the mark either. Being a potter, and therefore intimate with wheels and axes, I would prefer the term “uncenteredness” or off-center. What is striking about the etymology is that the axle-space referred to by the root kha is directly related to the notion of emptiness, silence, no-self—the very core of the matter is a space around which life spins, and dukkha implies a bad relationship to that core. We sit in order to settle, again and again, into a centered spinning around the empty axis-space.

BARBARA A. MILES

Middletown Springs, Vermont

HOT HAND FOLLOW-THROUGH

Concerning Lee De Barros’s letter in response to Larry Shainberg’s “Hot Hand Sutra”: some years ago I tried to adapt the approach described in Zen and the Art of Archery to shooting basketballs. Instead of focusing on the basket and trying to make the balls go through it, I concentrated on the way my hand felt on the ball and on the way my body felt during the act of shooting and following-through. I kept my eyes open but gave no more attention to the hoop than to anything else in the visual field. After a while, it seemed to me I was shooting much better. But I haven’t pursued this systematically, so who knows?

RICHARD BOYLE

Albuquerque, New Mexico

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.