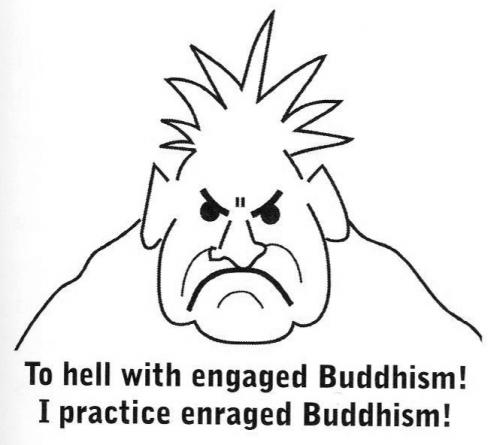

All Fired Up

Regarding the Summer 1998 issue, thank you very much for your elegant presentation of my poem “No” in “Seeing Red: Practicing with Anger” from my chapbook Fuck You, Cancer & Other Poems. But I am so angry, so pissed at the sloppy typo that marred the poem and my pleasure of seeing it in your pages. Line 24 in your version read “You don’t couch me.” In fact, and in my chapbook, the line reads “You don’t touch me.” What were you thinking, or not thinking? Did you rely on spell check for the final proof? Mindfulness indeed.

Rick Fields

Berkeley, California

Gerald Grow

I’m writing to personally thank all you writer-artist folks who have contributed to Tricycle all these years. I could never relate to “Tricycle-type” Buddhism. Maybe because I’m not a writer or an artist. But your issue on anger, that I can relate to—without trying to translate, interpret, or understand. So now I’m going back through past issues and “just listening” to you guys: be you straight, smokin’ or trippin’, straight, gay or bi; be you Jewish-Vipassana, Black-Nichiren, Anglo-Vajrayana, Second-generation-ethnic, or Gen-Xer from nowhere; be you manic or married, thoughtful or psycho, technical or poetic, dead or famous, reincarnated or enlightened. Or not. The words and images always got in the way before. I kept trying to see what you saw, so I never saw you. Now I’m just listening, and we’re all in the same place. I guess anger is good for something. Thanks.

Charmaine Kaczmarek

Chicago, Illinois

For the Record

I’m Eliot Fintushel, Noelle Oxenhandler’s husband and the father of our young daughter. I just wanted to point out, if that’s okay, to those who read my wife’s piece about her rejection and anger in a passionate love affair and how she dealt with it, and who may have assumed that it was me, her husband, she was talking about—that it wasn’t. Thanks.

Eliot Fintushel

Queen of Spades

I am not a gardener, and to read Wendy Johnson’s “On Gardening” essays in each issue of Tricycle gives me such vicarious garden experiences, I don’t need to be. Her writing is wonderful, something I imagine she has cultivated as diligently as Zen practice and her small plot of northern California soil. My life is so full with everything else, including eating organic veggies from a local community-supported farm, that I want to thank Ms. Johnson for allowing me the neat literary pleasure of thrusting my ungloved fingers into the dirt! Please provide us readers with her picture. Thank you.

Jeff Berger

Portland, Oregon

Tricycle responds: Here she is: Wendy Johnson, garden columnist

Zennists at War

Thank you for having published Josh Baran’s excellent review of the disturbing book Zen at War by Brian Victoria. Hundreds of statements quoted by Brian Victoria—on war as compassion, on identity of sword and Zen, on sword that kills and sword that gives life—were seen by their authors as expressions of nonduality.

A traditional formulation of nonduality is that samsara and nirvana are identical, are one, not two. Nonduality is not found in the teaching of the Buddha as reported in the Pali canon. As Bhikku Bodhi, the eminent scriptural scholar, wrote in a 1994 article, “From the Theravada point of view . . . the claim that there is no ultimate difference between samsara and nirvana, defilement and purity, ignorance and enlightenment . . . borders on the outrageous.” The Buddha, a pragmatic teacher for whom philosophical questions were irrelevant to the deliverance from suffering, did not speculate about a possible unified ground under our experience.

Centuries later, the Mahayana view that mental representations are empty of real substance led to the conclusion that the true natures of what representations refer to are not different from one another: ultimately samsara and nirvana are the same. Denying dualities in everyday life resulted in many Zen stories of apparent profundity. It resulted also in the perverse justification of the Japanese wars and atrocities in the first half of the twentieth century.

As Western Buddhists, we are not likely to be involved in such tragic uses of nonduality. Yet it is important for us not to put nonduality where it does not belong: in everyday life and in everyday practice where the dualities of greedy and generous, hating and loving, attached and disinterested remain dualities.

Jacques Maquet

Los Angeles, California

I very much enjoyed this issue of Tricycle. As usual, I found myself thinking deeply on a number of topics raised. In particular, the book review by Mr. Josh Baran on Zen at War and The Rape of Nanking captured my interest.

What I wanted to respond to was the judgment laid down by Mr. Baran on those who enacted the atrocities as well as those who were victimized. It seems to me that in a Buddhist magazine, pointing out the dangers of Zen-gone-astray as one of the causes for these atrocities should have been tempered with a Zen perspective of overriding compassion for all those involved in this chapter of world history. By compassion I don’t mean sympathy or righteous indignation followed by some kind of on-guard forgiveness. I mean a realization that all activities are embraced, supported, and created by this universe and perhaps more importantly, that all of these created activities are empty of any self-nature. However cold and callous this type of compassion may seem to Mr. Baran, the truth of it should be thoroughly investigated before judgment is passed in the name of Buddhism.

The words of D. T. Suzuki were sharply ridiculed by Mr. Baran. But the underlying perspective of this ridicule seemed to be: “To heck with insight into the empty nature of reality, we’re talking about human lives here!” However easy it is to relate to this point of view, we should also be able to see, acknowledge, and state that this perspective is, as much as anything it is criticizing, one-sidedly weighted from the perspective of a solidified self.

A more productive Buddhist lesson than trying to judge those who have lived in other times or even consciously trying to prevent similar things from happening again might be to first experience without a shadow of a doubt that those past atrocities are not something separate from what we are right now. They did not happen in some other time called “the past.” They’re still happening right now. You are those Zen masters extolling the virtues of war. You are that soldier who chopped off the head of that boy. You are that boy who was made to rape his own mother, as are we all. And for all your effort to avert it, if something similar happens again the blood can be nowhere else but on your hands.

Before judgment in the name of Buddhism occurs, we are all asked by this tradition to first realize that every activity that has ever been or will be is precisely that which makes up the very content of this moment in which we now live. Mr. Baran seems unable to accept in any way that Buddha-nature could be said to function in such horrific activities….Well, it did, didn’t it? “How can we absorb these overwhelming contradictions?” he wrote. We absorb them quite simply through the understanding that all of us have been duped in the past, we are all being duped now, and we will all be duped in the future. There is no other alternative to being duped in this world or the next. In fact, being duped continually is the very essence of this world and of all other worlds.

Samsara can be nothing other than nirvana. Nirvana can be nothing other than samsara. Everybody has always done just exactly what they have seen fit to do given the circumstances of their lives, no more and no less. Buddhism’s gift is not pacifism or moral superiority but its offer of a wonderful insight into the irresistible charade of life and death. This gift enables us to understand and play the game without suffering from its irresistibility or ridiculing others for the temptations they gave in to. So actually it’s perfectly okay to blow your horn and lead a charge in questioning the virtues of Zen or Buddhism or the way others failed to practice it. But you should also have the courtesy to mention that the moment you open your own mouth, you’ve joined all those you rail against and have condemned yourself, and all of us, to eternal samsara.

Zen Monk Kigen

To the Academy

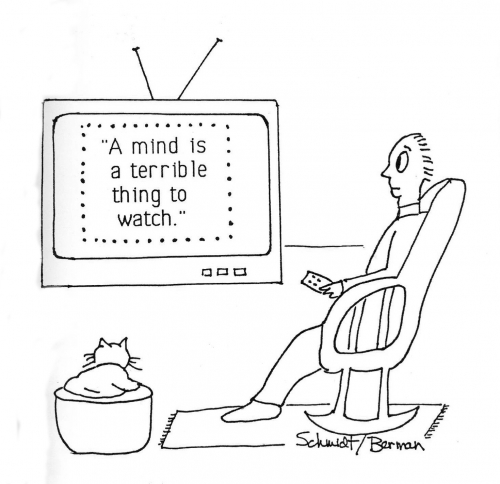

I was quite pleased to once again read “From the Academy” by Professor Donald S. Lopez, Jr. The professor’s article addresses the great Buddhist theme of identity. Professor Lopez admits to being less than enthusiastic about proclaiming himself a Buddhist to his students. Such a position is not at all uncommon in Americans who are deeply involved in things Buddhist. Is this because Americans approach Buddhism through meditation rather than ideology, and so are afraid of any ideological posturing? Or are Americans invoking the central practice of Buddhism, anatta, the rejection of identity?

Professor Lopez’s dilemma is that the “practice” of religion is viewed as contradicting its study. In just about every other academic discipline, practice is viewed as enhancing study. But this was not necessarily so in all ages, nor is it even so in all countries today. In the Middle Ages the practice of chemistry and physics would have had a stigma similar to that attached to the “practice” of religion today. And probably in some theocratic societies today they still do.

I think the common view of what Buddhism is and how it is practiced needs to be expanded. Professor Lopez’s scholarly approach to Buddhism is no less a practice than the stereotypic one of sitting cross-legged. I am not even convinced that this narrow form was what the Buddha and his disciples engaged in as the principal mode of practice. The earliest disciples were in fact enlightened by lectures and convincing arguments. Their “meditation” in modern terms was simply study.

Liam Martin

Brooklyn, New York

Going to the Dogs

Thank you so much for your excellent magazine. I have been reading it for some time, and it just seems to get better and better. Compassion comes through in every word that is printed in your pages. I was especially moved by the number of your readers who wanted to contribute to feeding the dogs at Watklang in Thailand. As a practicing Buddhist of Thai descent, I was very moved by Americans taking such a humanitarian interest in what is happening in Thailand. But I must say that I think what Tricycle really lacks is recipes. I would love to read more articles about Buddhist cuisine, especially recipes for chicken, which tastes a lot like dog. It is a pity that there are no good restaurants that serve dog in this country. It is one of the many things I miss about my native country. But I make do with chicken. Chicken is the new black. It is very fashionable to eat chicken these days. Perhaps you can devote an entire issue to the Buddhist uses of chicken. Or perhaps even dedicate the magazine to Buddhist chicken cuisine. I hope you will continue to publish your much needed journal.

Alatajai Phojainakong

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.