In October of 1980, the Vipassana meditation teacher Jack Kornfield called me at the Zen Center of Los Angeles, where I was a resident staff member, to ask if I could lend a hand with something. The well-known Cambodian Buddhist monk, or bhikkhu, the Venerable Maha Ghosananda, would be arriving the next day on a flight from Bangkok, and Jack asked if I would meet him at the airport and keep him company during what would be a long wait for his connecting flight to New York. I said I would be happy to do it.

Actually, I felt privileged. From previous conversations with Jack, I knew of Bhikkhu Ghosananda and the extraordinary humanitarian work he had done among the hundreds of thousands of Cambodian refugees stranded in squalid “holding camps” near the border, in Thailand. Starting in 1975, they had fled the killing fields of the Khmer Rouge; they had fled the civil war between the Khmer Rouge and the Vietnamese-backed Heng Samrin regime; and they had fled the starvation that was the legacy of a decade of bloodshed catalyzed by the U.S. bombing raids in 1970. By 1979, the situation had reached a crisis point, as tens of thousands faced imminent death from starvation and disease, and relief agencies from around the world responded with what turned out to be amazing effectiveness.

The immediate crisis was largely averted, but the sheer misery of the camps was unrelenting. The physical conditions were oppressive, as were the psychological conditions. Most refugees had been in the camps for years, thoroughly uprooted, living in constant fear and uncertainty, knowing that their fates depended on political forces beyond their control or even understanding. And there was danger. Khmer Rouge soldiers, having fled the new regime, maintained an intimidating presence as they used the camps to reorganize for a counterinsurgency.

Of Cambodia’s 60,000 Buddhist monks, about twothirds were killed under the Khmer Rouge, and almost all the rest were forced to defrock. Maha Ghosananda, who had spent most of his monastic career in Thailand and India, was out of the country when the slaughter began, and he was now one of the very few senior Cambodian bhikkhus. In 1978, he cashed in a plane ticket to France he had been given; he used the money to print 40,000 leaflets of the Metta Sutta, the Buddha’s discourse on the power of lovingkindness, and distributed them throughout the camps. He helped establish temples and schools. He brought together representatives of the different groups; victims, members, and even leaders of the Khmer Rouge came together in common cause. As many as 10,000 attended his dharma talks.

But then the Khmer Rouge, with the cooperation of the Thai military, began to coerce refugees into preparations for “repatriation.” In response, Maha Ghosananda circulated a leaflet telling the frightened refugees they were not required to return, and he offered his temple as a sanctuary to anyone who asked. To many Thai officials, he had gone too far, and he was banned from the camps. So now he was coming to the U.S., his first time in the West, to represent the refugees and to continue the work of cultural and religious reawakening.

Related: The Power of Forgiveness

I arrived at the gate with plenty of time to spare. As the passengers from Maha Ghosananda’s flight made their way up the concourse, I stepped forward, placed my hands together in gassho, and tried to make myself appropriately visible. Then I spotted a saffron-clad bhikkhu coming my way, walking in a stately manner. His skin had a healthy bronze sheen, and though he was of average height, he appeared tall, in the way that those of dignified bearing often do. “This,” I thought, “this is a monk who could face down the Khmer Rouge!”

Strangely, though, the bhikku’s eyes were not meeting mine. Rather, they were focused about fifteen feet to my left, where several Southeast Asian families were just about jumping out of their skins in gleeful anticipation. The bhikkhu’s face broke into a wide smile, though his pace didn’t pick up one iota. Finally he arrived, and the lay folk erupted in such a display of tears and laughter that people stopped in their busy tracks to smile along.

But where, I now had to wonder, was my bhikkhu?

By this time, even the pilots and flight attendants were walking by, and I was starting to worry. Then, looking down the concourse, I saw another bhikkhu. This one didn’t quite have what you would call heroic bearing, but since he was the very last passenger off the plane, I figured he had to be my guy. His robes faded and worn, his head bent purposefully, he came scampering up the concourse, the rapid action of his legs seemingly at odds with the modest distance he actually seemed to be covering. It was like he was going the wrong way on a moving sidewalk, only he wasn’t. I snapped into proper gassho posture and prepared to greet him. But my timing was thrown off by his peculiar gait, and I began my bow while he was still a good five yards away, so I came up just as he was bending over. Feeling it would be improper to complete my bow before my venerable guest had completed his, I went down for another; the bhikkhu, seeing me bent floorward, decided to return the favor once again. We repeated this comedy for several rounds. It occurred to me that he would continue answering my bows for as long as I offered them, and I eventually stopped and blurted out something on the order of “Welcome to America!” We stared at each other for a moment, then we smiled, then we laughed. And just like that, my friendship with Maha Ghosananda was sealed.

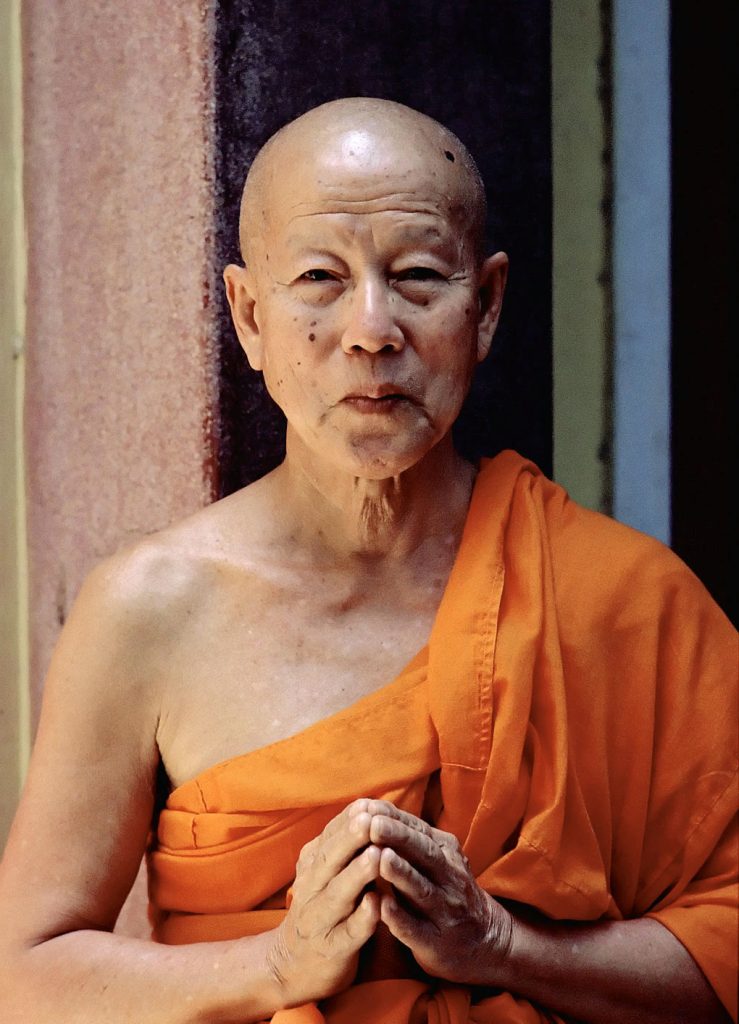

His smile was wonderful. He had a kind countenance, with soft brown eyes, a broad nose, and a sallow complexion, and when he smiled the corners of his eyes crinkled up adorably. This, along with his diminutive frame and gentle demeanor, gave him a gnomish aspect. There was also about him something more than a little otherworldly. He was like a Hobbit, I thought, and it later occurred to me that if Tolkien had, for some reason, seen fit to put a Buddhist temple in the Shire, he would surely have created someone just like Maha Ghosananda to be its monk.

Without a doubt, Maha Ghosananda was one strange fellow. Whether one construed this as mere personal eccentricity, an odd species of detachment that was—for better or worse—the result of years of devoted meditation practice, or an indication that he might actually be quite off his rocker, there was no getting around the fact that Maha Ghosananda had a peculiar and tenuous relationship to everyday reality. There was a marvelous paradox that played about him. Wherever he went, he appeared curiously out of place; at the same time, he seemed always to feel right at home. He greeted the world freshly and with affection, and he didn’t seem all that concerned with how the world responded. Often people would balk upon meeting him; it was hard to know just how to take this guy who was suddenly treating you like his best friend in the whole wide world. But he was pretty irresistible.

Jack had told me that Maha Ghosananda was fluent in ten or twelve languages. What he had not told me was that Ghosananda had a way of putting his linguistic skills to use that sometimes made sense only to him. He might, for example, mix several languages together in a single sentence, beginning with, say, English, switching to French at the midpoint, and ending with a fillip of Pali. Or he might speak in a language you didn’t understand, reasoning that you would pay better attention that way. Or he might respond to something you said by putting his palms together and chanting, perhaps in Pali, perhaps in English, perhaps in Japanese—he had a lot of languages to choose from, and his criteria for employing one rather than another was entirely his own. Or he might reach into his shoulder bag and hand you a flyer.

His bag—that was something. It was medium-sized, with a nicely crafted reddish folk design. The stitching was perpetually stretched tight, as the modest bag carried a load fit for a large suitcase. It was stuffed with magazine and newspaper clippings, photocopies of selections from Buddhist texts, inexpensively printed Thai dharma books, and who knows what else. I recognized material in at least three distinct scripts. The bag seemed bottomless. Like a magician’s hat, it seemed to defy the laws of physics. Maha Ghosananda would rummage around in this portable Fibber McGee’s closet, and he would keep at it long past the point at which social convention dictated that he desist. Eventually, though, he would look up from his task, pleased that he had found what he had so single-mindedly sought. But there was no telling what he was going to hand you. It might have direct bearing on the topic at hand, or—just as likely—its connection was one only he could fathom.

Maha Ghosananda ’s flight was not for another six hours, so I suggested I take him back to the Zen Center. It was a short trip but long enough for me to get a feel for his special way of communicating. When we arrived, I brought him to pay respects to the center’s abbot, Taizan Maezumi Roshi. Maha Ghosananda was positively thrilled about this; I was not. Roshi was generally a warm and gracious host, but he was not what you would call a sweetheart of a guy, and when he lost patience with someone, he could be quite the grump. I was worried this might go badly.

After the initial bows, I provided brief, somewhat formal introductions, and then Roshi’s wife, Ekyo, served tea. Roshi asked Maha Ghosananda about the situation in Cambodia and his work in the camps, and Ghosananda went for his magic bag. I knew this approach was not going to fly, so I jumped in. I filled Roshi in on the camps, told him what I knew of Ghosananda’s work, explained what had led to his coming to the States, and as I did, Ghosananda pulled out assorted items, which he then handed to Roshi, who looked at each one for a second or two and then set it down neatly beside him. When Ghosananda did speak, he addressed the Cambodian tragedy in only the most general Buddhist terms; he quoted from the Metta Sutta and the Dhammapada; he chanted as well. Roshi grew silent, his expression impassive.

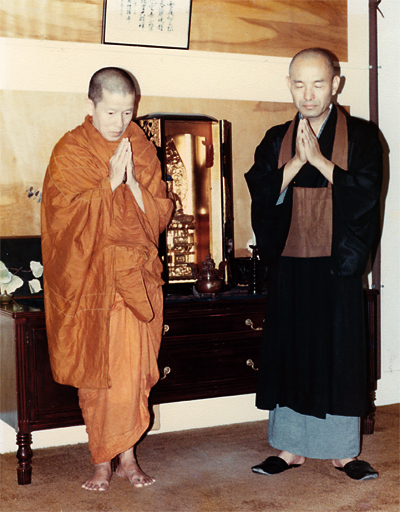

We settled into a minute or two of quiet. Then Roshi rubbed his hands together, rose from the table, and invited Maha Ghosananda to offer incense at the household altar. I was relieved. The meeting didn’t seem to have gone well, but it was almost over, thank goodness. We adjourned to the next room, where Roshi and Ghosananda bowed and offered incense, while Ekyo and I looked on. Then Ghosananda knelt before the altar and chanted in Pali. He hadn’t been chanting for long when Ekyo nudged me and, eyes wide with surprise, whispered, “Do you see Roshi? He’s weeping.” And sure enough, she was right.

Courtesy of Martha Ekyo Maezumi

I tried to keep in touch with Maha Ghosananda, but it didn’t really seem to work. I kept track of his whereabouts and wrote to him from time to time. His responses, though, were always the same. I’d soon receive back an enormous, fat envelope, reinforced with tape to keep it from bursting, and inside would be the same assortment of clippings, scriptural selections, and such that I had previously seen him pull out from his magic bag. I worried about him, about how he was making his way in the U.S., and I suppose this was his way of telling me he was okay. Still, after several such exchanges, I let our correspondence, or whatever you’d call it, trail off, while I tried to keep tabs on him through second- and third-hand parties. It would be nearly three years before I saw him again.

In June 1982, in New York City, the United Nations conducted its second special session on disarmament. I timed a visit to my parents, who lived in the city, to coincide with the special session, as that would allow me to participate in some of the peace activities happening around town. Much of my time was spent at a three-day interfaith conference called Reverence for Life, which, with its list of notable guests and presenters—Joan Baez sang, Linus Pauling spoke, Thich Nhat Hanh gave an inspired reading of his Whitmanesque poem “Please Call Me by My True Names”—drew a large group of participants from around the country.

On the first day of the conference, entirely by surprise, I ran into Maha Ghosananda. He was, as usual, bustling about, handing out leaflets, bowing here and chanting there. His back was partially turned when I approached, and, my hands in gassho, I said his name. He turned and took just a moment to recognize me. His eyes lit up, and—using my Buddhist name—he exclaimed, “Brother Taido!” He leaped at me and took me in a great bear hug, pinning my arms at my sides and squeezing me with surprising strength. He held me for an awkwardly long time. I felt more than a tad self-conscious, but also oddly elated.

Soon after this a couple of the conference’s planners, having seen me and Maha Ghosananda together, asked if I would accompany and keep an eye on him during the conference, which was no problem, since I was already planning on it. There was, however, one particular thing they asked if I could help with that was not something I had thought about. Ghosananda was slated to give a speech at the conference, but there was a problem. It seems he was intent on lecturing in French. The conference planners had explained the disadvantages of addressing an English-speaking audience in French, but Ghosananda was having none of it. Could I, they asked, somehow get him to change his mind?

I said I would try, but added that the chances of success were pretty slim. As I expected, speaking with him about it accomplished nothing. He simply had his mind set on the idea that the audience would listen better if they didn’t understand what he was saying. I was familiar with this tenuous line of reasoning, and I dutifully reported it back to the planners, being quick to point out that I was only explaining, not endorsing it. They seemed deeply baffled that someone like Maha Ghosananda, someone who was without question a heroic figure in the struggle for peace and human rights, could have such harebrained ideas. I wondered why I didn’t feel the same way.

On the second day of the conference, after the afternoon session, Maha Ghosananda told me he had to see someone and asked if I would come with him. I said sure, and asked where we would be going. He pointed south, toward downtown. The conference site was a church on Park Avenue, maybe five or six blocks above 86th Street. We started walking south, and when we got to 83rd Street, we headed east to Lexington so I could stop at my parents’ apartment.

I had made plans to have dinner with my folks, and since I didn’t know how long this business was going to take, I needed to let them know that I might be late. Plus, I had only taken a few dollars with me, and I had more cash up at the apartment, which I thought we might need. I explained to Ghosananda that we were just going to pop in and pop out and be on our way.

When we got there, my dad was still at work, as I expected, and my mom was in the den, as I knew she would be. Six weeks before, she had broken her ankle in a tennis mishap, and the long hours of convalescence did not suit her active temperament. I called out hello and announced that I had brought a guest. I found her sitting in her chair, reading, her bad leg, still in a small cast, propped up on an ottoman. She smiled when she saw me, but when Ghosananda stepped into view, she shot me a look that said, “Okay, Mister Buddhist, start talking.” I was just about to begin when Ghosananda’s howl erupted, and in the next moment he dashed across the room and threw himself at my mom’s feet. “Oh, Holy Mother! Oh, poor Holy Mother!” he cried out. My mom looked at me for an explanation. I shrugged my shoulders.

Related: Silence in the Pagoda

As Ghosananda busied himself massaging her foot and ankle and tearfully reciting prayers, I explained a little about him. Given the immensity of suffering he had ministered to, I couldn’t account for why a broken ankle would be such a big deal to him, except to say that he doesn’t make distinctions about such things in the same way that everyone else does. But the matter of scale didn’t seem to bother my mom one whit, and it wasn’t long before she was quite enjoying all the fuss. It seems to be in my mom’s character to feel that she does not get her fair share of sympathy and understanding, and with Ghosananda I believe she felt, perhaps for the first and only time in her life, truly seen. She would smile and shake her head, as though it were all too bizarre for words, and say things like, “I can’t wait to tell my bridge club about this!” Still, she didn’t make a move to stop him. Eventually, though, I did.

When we got down to the street, I asked if we should walk or take a cab, and Maha Ghosananda was clear about his preference for walking. I didn’t ask where we were going—I don’t know how I could have missed that one— and we just headed south. We walked and we walked, and I kept thinking that any minute Ghosananda was going to say we’d arrived, but no. Finally, when we got to Washington Square, he handed me a balled-up piece of notepaper on which was scrawled an address just a few blocks away. I was tired and thirsty and my feet hurt, and I said a bit too sharply, “Why didn’t we just take a cab?”

“No money,” he said.

This was a puzzling response. I knew that as a Theravada monk he was not allowed to handle money, and I knew that he knew that I knew that.

“No,” I said, “I know you don’t have money. I have money. I could have paid.”

Then Ghosananda reached deep into the folds of his robe and pulled out a roll of twenties wrapped in a rubber band and held it aloft. It was so thick it would have made Tony Soprano’s eyes cross.

“I have money. See?”

Things were not making much sense here. I pulled his arm down and told him that he shouldn’t wave money around like that in New York City. Then I suggested we keep walking. Soon I realized that by “no money” he meant he didn’t want to spend any. I suppose he figured that since it was his errand we were on, it would not have been fair to ask me to pay for the cab. But what I could not figure out was what he was doing with all that cash.

When we arrived—it was a basement apartment, with bars on the windows and a heavy steel mesh outer door— Ghosananda rang the bell, and several seconds later the door was opened by a tiny, stocky, fiftyish Asian woman with a helmet of black hair. She stared wide-eyed at Bhikkhu Ghosananda for several beats, and then let loose a great keening wail. Her knees buckled and she collapsed to the floor, where she sat and sobbed. Ghosananda patted her on the head and spoke gently to her in what I assumed was Cambodian. Meanwhile, faces began to poke out into the dark hallway, and seeing who had arrived, her family rushed out and converged on Ghosananda. There were young kids, a couple of teens, a grandparent or two, and what looked to be her husband. They were absolutely beside themselves, crying, laughing, everyone talking at once, and everyone running around trying to get organized enough to serve tea to their honored guest. Ghosananda acted like he had done this a thousand times before, and probably he had.

We were led into the living room, where we were both seated on a couch while everyone else sat on the floor. I tried sitting on the floor as well, but they insisted I remain on the couch. Apparently just bringing Maha Ghosananda qualified one for bhikkhu-like status. The animated conversation was in Cambodian, but I was content just to look on. Besides, I could barely hear what was being said, as I was seated next to the TV, which for some reason had been left on, blaring. After several minutes, Ghosananda took out the roll of bills and handed it to the mom, who, barely giving it a glance, passed it over to her teenage son.

I tried to ignore the TV, but it was incredibly loud. I couldn’t for the life of me understand why it hadn’t occurred to anyone to turn it off, yet I felt it would be impolite to say anything. Gradually, my attention went to the sound of the movie on the TV. The music was so familiar—I knew this movie. Suddenly it came together. It was the Godzilla music! I turned to the TV just in time to see his massive head emerging from Tokyo Harbor. Godzilla let out his terrible roar, and a jolt of excitement ran through me. When I was about seven or eight, Godzilla had been my hands-down favorite movie. I hadn’t seen it in close to twenty years, and now, in this most unlikely of situations, here it was.

“It’s Godzilla, on the TV!” I said to one and all. “I love Godzilla.”

Everyone turned to me, still smiling, but without a hint of comprehension. I pointed to the TV and nodded, indicating that I was fine; they nodded, indicating that they were happy that I was fine. They then returned to their conversation, and I returned to Godzilla.

We eventually said our goodbyes and Maha Ghosananda and I headed back uptown. I said that this time we were going to take a cab, but Ghosananda said no.

“And why would you possibly say no?”

Ghosananda looked stricken. “No money,” he said.

I stared at him, trying to tell if he was just messing with me. I decided that he wasn’t, that he couldn’t be because putting people on simply wasn’t in his repertoire.

“That’s okay,” I said, “I’ve got money.”

I hung out with Maha Ghosananda for the rest of the conference, but we never did see each other again after that week. He continued to do great work in the world, and in time the world took notice. By the time of his death, in March 2007, he had received several prestigious humanitarian awards and been nominated six times for the Nobel Peace Prize. He was honored as the Supreme Patriarch of Cambodian Buddhism. Many spoke of him as the Gandhi of Cambodia.

When I read of his passing, I performed a small memorial service with my wife, Liz, and daughter, Alana. Sitting beside the household altar, exactly where it has been for almost thirty years, was a photo, taken by Ekyo Maezumi, of Maha Ghosananda and Maezumi Roshi.

What a strange fellow he was. As he moved through the world, he seemed less burdened by self-concern than are all but a very few. I imagine, though, that he had his own iron sack of misery to carry around. Perhaps his otherworldliness was as much a retreat from life’s vicissitudes as it was a character trait. Still, one would have to search long and hard to find someone with so loving and generous a heart. And while Ghosananda might have been weird, he was also, especially in what matters most, wise.

When Cambodia was destroyed, and hundreds of thousands, including his whole family, were massacred on the killing fields, Maha Ghosananda chose to ride with the Better Angels of his nature instead of some other gang. He rode a long way, and—whether it meant leading a peace walk through the embattled countryside of his homeland or giving an ankle massage to a young friend’s mother on New York’s Upper East Side—he took us all along for the ride.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.