On the final day of my first sesshin—a seven-day Zen meditation retreat—at the conclusion of a six-week training period, I asked the presiding teacher, Taizan Maezumi Roshi, if he would accept me as a student. Formal interactions have never come naturally to me, but I felt it important to do this with as much formality as I could muster. I went into my last dokusan—a private, highly ritualized interview with a Zen teacher—with that mix of excitement and anxiety that comes with sensing one might be about to turn a new page in one’s life.

I entered the dokusan room, gently closed the door behind me, did my bows, sat on my knees Japanese-style, in seiza, and scooted up as close as possible to sit face-to-face with Maezumi Roshi. I got right to the point:

“Roshi,” I said, “I feel a deep connection to you and your teaching and I would like to continue to study under your guidance. Please accept me as your student.” Or words very much like those. It was a long time ago—1977, to be exact.

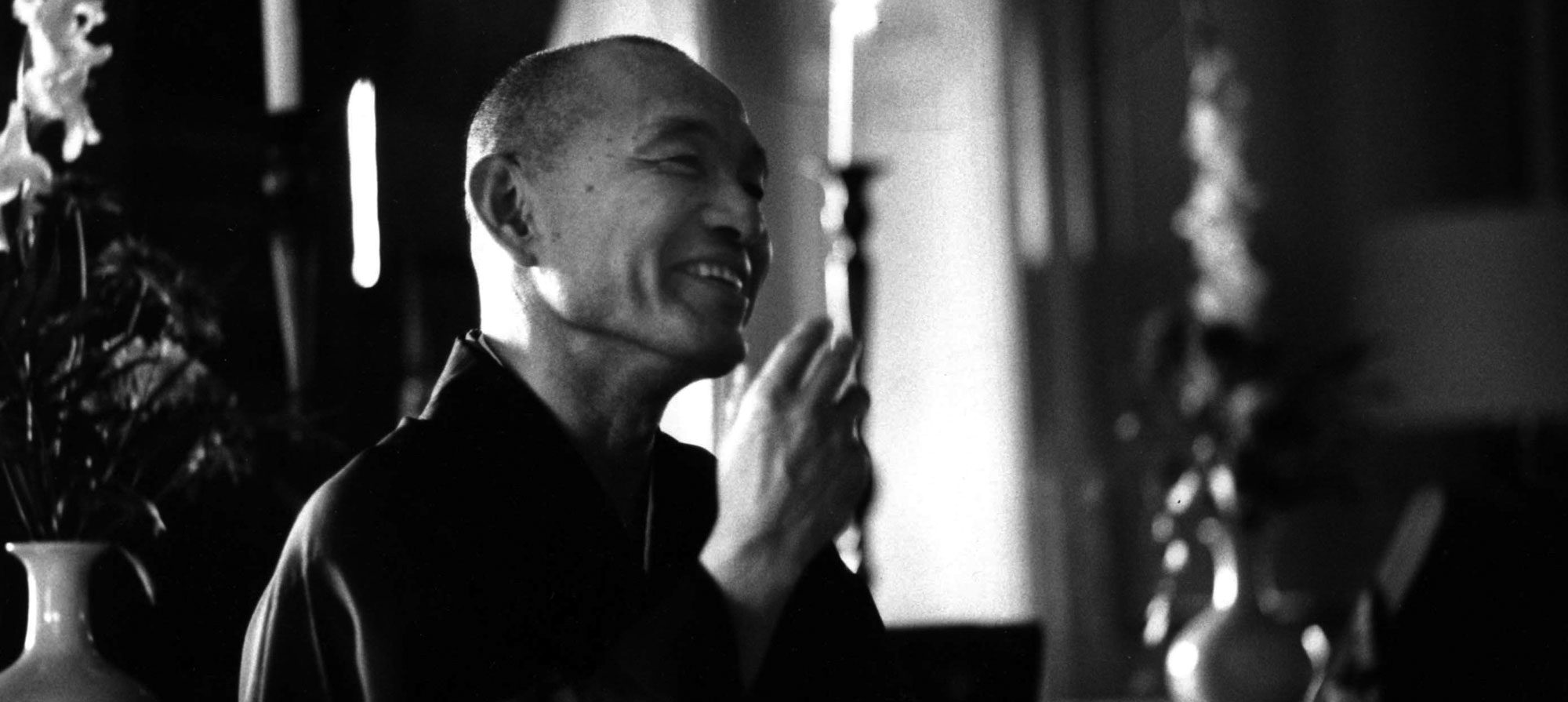

While my memory of my words is imprecise, my recollection of Roshi’s response is more accurate. He was silent for some seconds (uncomfortable ones for me), staring ahead impassively with the stern frown that is something of a characteristic among Japanese Zen masters. I assumed he was rolling the matter around in his mind, but it soon became apparent that he was rolling around something different.

“Are you Jewish?”

I wondered if maybe I hadn’t heard him correctly, but really I knew I had. In that case, however, what the hell was going on? My mind raced. Was this some kind of Zen question, like if I say yes I get slapped and if I say no I get hit with a stick? Do I walk out of the room, as in the old koan, with sandals on my head? Maybe, but no. It didn’t seem to have been asked in that kind of spirit.

Was he a bigot? That didn’t fit either. To accompany him for the training period, which took place in Boulder, Colorado, Roshi had brought along three senior students from his home base at the Zen Center of Los Angeles (ZCLA), and two of them were Jewish. Plus, I had been his attendant for the previous six weeks and I’d seen no indication of any such sentiments. So bigotry toward Jews wasn’t behind it.

What the hell was going on? Was this some kind of Zen question, like if I say yes I get slapped and if I say no I get hit with a stick?

Maybe he had somehow, with some preternatural insight, tuned into my deep inner conflicts about my Jewish identity, and he was going to shine a light on them. That kind of guru story was extremely popular back then, but as appealing as the thought was, it seemed entirely to miss the mark. Besides, Maezumi Roshi just didn’t seem to be that kind of teacher.

Or maybe I was a character in a Jewish joke set in my own life. This was a familiar feeling that made it seem like a plausible, if nonsensical, conclusion. It didn’t actually explain anything at all but only reflected my own skewed sense of myself. On the other hand, it at least offered the possibility of a good punch line.

But really I hadn’t a clue about why Roshi asked the question, so I just answered in the affirmative: “Uh-huh.”

Roshi smiled and kind of shook his head good-naturedly. “So many of my students are Jewish,” he said. I had no ready response for this, but that was fine, since he didn’t seem to want one. He went on, “Genpo is Jewish, and so is Ryotetsu.” Genpo was one of two priests who had come to Boulder with Roshi, and from our conversations I knew he was Jewish. Ryotetsu was ZCLA’s tenzo, or head cook—a very important position in a Zen practice community—and had come to fill that same role during the Boulder training period. I had a pretty good sense that he too was a fellow tribesman. So while I still didn’t get the point, I gave a slight nod to show I understood at least something.

Roshi then added, “Maggie’s not Jewish, but that’s OK.”

Now I was lost again. I was, of course, glad to hear it was OK that Maggie wasn’t Jewish, but, you know, who was Maggie and why was her not being Jewish even an issue? Such questions seemed off the point, however, as Roshi seemed to be taking this all somewhere: “Tetsugen and Yuho keep the Jewish holidays.”

Tetsugen I knew by reputation; he was Maezumi Roshi’s top student. I surmised—correctly, as it turned out—that Yuho and Tetsugen were married. I can’t remember with much exactness how the conversation went after that, but the gist of it was Roshi talking, in his accented and idiosyncratic English, about his Jewish students, kind of like this:

“Kakushin and Myoku are Jewish. He’s a lawyer. I think they are both from Brooklyn. Their son Ryokaku, see, he’s a monk. Kakushin and Tetsugen, they are cousins. It’s kind of a nice thing, huh. Ryoshin, he is engineer. He just moved into the center. Genmyo’s family, very religious. He can’t tell them what he is doing, but they are in New York anyway. Yuho is also from a strict family.” And on it went. The thing about it was, once we got past the cook Ryotetsu, I didn’t know any of these people. Yes, it was true: I was Jewish and so were they (except of course for Maggie, but as I’d been informed, that was OK). If there was a point to all this, I wasn’t getting it.

It was summer and the small room was hot and thick with incense smoke and beads of sweat were now dripping down my sides and Roshi continued talking about Jews at the Zen Center. He was into it. Eventually it occurred to me that what was going on was that he was just following out the thread of something that had struck his interest. He was just talking. A few moments later, Roshi seemed to notice this as well. He stopped abruptly, let out a “Hrummph!,” rubbed his bald pate—a punctuating gesture I was to see him do upwards of a thousand times over the years—and said, “Where were we?”

I tried not to laugh, but I did, a little. So did Roshi. A little less. Then I said, “Well, I had asked if you would accept me as your student.”

“Oh, that’s right,” he said, nodding in recollection. “Sure. Sure.”

Then he picked up the small bell used for signaling the conclusion of dokusan, rang it, and I did my bows and left. And that was that. It sure wasn’t the sort of penetrating exchange that makes it into the koan collections. It didn’t even have a good punch line. But there was something about it that, in its oddball, unintended, peculiar way, fit perfectly with the imperfect fit that shaped our affinity.

Related: Buddhism Meets Hasidism

A few months later, I moved to Los Angeles, where I was fortunate to be given a residential staff position in the growing Zen Center community’s small publication department. I spent the next seven years—six at ZCLA and one at a recently formed branch temple in upstate New York—as a full-time Zen student, rising before dawn for two hours of meditation and liturgy and ending the day the same way. Work all day, communal meals, and a day and half off each week. At the end of every month was sesshin, alternately three or seven days.

It is no secret that Zen practice can be quite demanding, and it certainly was for me. I was not what you might call a natural. But I took to it somehow, to the completeness of it, and this was new for me. I had come to Buddhism by way of the Theravada tradition, and after several years during which I rode the rails of the Vipassana retreat circuit, I moved to Boulder to study in the community of the Tibetan master Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche. These were formative experiences for me, though the good fit that so many others found always eluded me. But that good fit—I felt that at ZCLA, and it meant a lot. To live in a manner that draws together one’s energies and joins them with those of others, and to do this in pursuit of one’s best sense of purpose—this is surely something to be prized.

A good fit is not the same as a perfect fit, if such a thing even exists. Rather, a good fit contains good imperfections, things that don’t fit, problems you can sink your teeth into.

Right near the close of morning and evening liturgy, the leader, or ino, chants, “May we realize the Buddha way together.” There is a sense of life’s wholeness conveyed by this simple phrase. “Realize” and “Buddha way” and “together” seem to be each fully implicated in one another, as though one could kind of reverse the order and say that “together” is, from a certain perspective, the Buddha way realized. This sensibility helped carry me when my own strength to meet the rigors of training was insufficient. I was carried as well by the rhythms of daily life and practice. All of these gave practice a background, a wider field that could contain its mental and physical hardships. And, as if by accident, with time this field found a tendency to peek out, of its own and recognized only by sidelong glimpses, into the foreground.

I studied closely with Maezumi Roshi for those seven years. Typically, I, like his other residential students, saw him in dokusan two or three times a week to present my koan, and during sesshin that many times a day. No less important were unplanned encounters, informal interactions, administrative discussions, and the countless observations and impressions that are the stuff of community life. To say I studied closely—this is not a comparative claim. I was not a top-tier student by any means. I am speaking, I suppose, mainly of a kind of shared understanding, something elusive and hard to get a handle on. It is like the resonance of a note so low you can’t hear it but you know it by its effects: water in a glass ripples, a wooden armrest vibrates, a herd of elephants appears at the front door. This resonance can’t be pinned down, but its very unpindownableness is of a piece with the world made present in practice, and close study, to some degree or another, helps usher one into it.

A good fit is not the same as a perfect fit, if such a thing even exists. Rather, a good fit contains good imperfections, things that don’t fit, problems you can sink your teeth into. One circles around them, going a bit deeper with each turning. My good fit with Maezumi Roshi and the Zen Center community was rich with imperfection, some of it—but not all—for the good. I think that chief among these creative conflicts was my antipathy toward ritual.

Anyone with even a passing familiarity with Japanese Zen knows well that it is a highly ritualized form of practice. Like many others, I imagine, I was by turns put off, confused, suspicious, flustered, or just frustrated because of all the ritual. It is not hard to see how I came by this attitude. With an outlook shaped significantly by the assumptions of modern secular culture, these traditional forms appeared to me, self-evidently, as a kind of extraneous baggage carried over from Asian culture. It did not occur to me until much later that my own attitude was anything but impartial, that it was in fact the baggage of my own culture.

My skepticism was also, no doubt, augmented by my particular background in Buddhism. The Vipassana tradition as I encountered it is itself an adaptation to modern sensibilities, one that strips down Buddhism to what it has constructed as a meditative core. Although Trungpa Rinpoche was in the highly ritualistic Vajrayana tradition, a virtual signature of his teaching was a deeply cautious and questioning attitude toward the tendency to render exotic or romanticize Asian forms. By contrast, Maezumi Roshi, like most other Zen teachers at the time, taught his tradition with rituals intact and with little explanation. It was pretty much Chant this, ring that, and when in doubt, bow.

Despite my reservations, I participated in the ritual life of the community fully, or at least as fully as I was able. I wanted to train in Zen and, well, this was just what you did. Over time, and mostly without my noticing it, these forms came to make a kind of sense to me, and they did so in their own way. If one takes up a musical instrument or a sport, there is certainly much learning to be gained by instruction and the conscious pursuit of goals, but there is also much that is learned less directly, largely through repetition and absorption. A sense of things—of timing and spacing, of how things work, of how things fit together—insinuates itself through the action of the body and the connected work of imagination. I found that ritual life was affirmed not through reason—in fact, where reason was concerned I long continued to be pretty skeptical—but through meaning as it was absorbed through doing. A whole, irreducible world of meaning, including an attitude commensurate with receiving that world, is condensed and transmitted through symbolic action. Ritual appears as the tradition enacting itself.

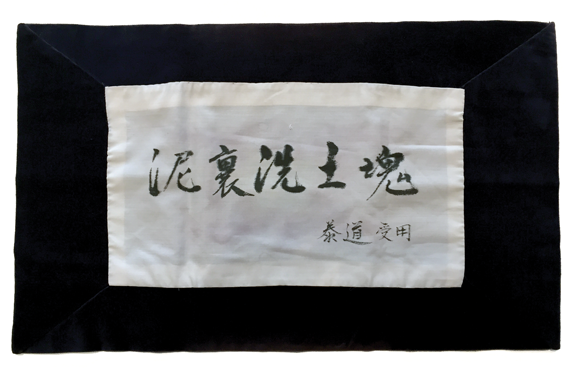

My appreciation of ritual was still pretty rudimentary when I asked to take jukai, the ceremony in which one “receives” the 16 bodhisattva precepts and thereby formally acknowledges the guidance of the three treasures—the Buddha, the dharma, and the sangha. Still, I very much wanted to do it. One aspect of jukai is receiving from one’s preceptor a rakusu, a garment worn around the neck as an abbreviated version of the Buddha’s robe. A few days prior to my jukai, Maezumi Roshi offered to do a calligraphy inside the cover of my rakusu. I of course said yes, and he handed me a photocopied stack of papers entitled something like “Zen Phrases,” which I then took back to my room. There were, as I recall, hundreds of these sayings, most of them quite short—between five and fifteen words. They were typically used in conjunction with koan study, as jakugo, or “capping phrases,” with which students might demonstrate or be tested on their understanding. Having to select one saying from so many was at first unsettling. Knowing that I am the type of person who can go into a market and easily spend 20 minutes comparing different types of salsa and come out having bought nothing, I feared I might get sucked into a wormhole of indecisiveness. But it wasn’t to be. As I read them through, one saying just jumped out and grabbed me: “To wash a clod of earth in the mud.” If you had asked me what I found so compelling about this particular saying, I would have been hard-pressed to answer. But meaningful things often begin with such unripe understanding.

As we at ZCLA were well aware, in matters of purity Maezumi Roshi did not set a high bar.

I brought the saying, along with my rakusu cover, to Roshi. He smiled and nodded when he read what I had selected. Roshi was not generally given to dramatic demonstrations of approval, so this seemed, by normal-people standards, pretty extravagant. But the moment passed in the time it took to notice it, and with a gruff “OK,” he signaled me to leave and returned, head bent, to the papers before him. During my jukai ceremony, Maezumi Roshi took a few minutes, as he generally did, to speak about the meaning of my dharma name, Shugaku Taido, character by character and as a whole. He also, though, made an unusual detour to talk about the saying he had calligraphed in kanji—Chinese characters—in my rakusu cover. He spoke of “to wash a clod of earth in the mud” as the practice of the Bodhisattva way. He said a little more than that, but that is the part I remember. It struck a chord, and it has stayed with me and has worked on me ever since.

Related: The Buddha’s Robe

As with any teacher, Maezumi Roshi’s different students met him and learned from him in various ways. For me, “To wash a clod of earth in the mud” became a touchstone of Buddhist life. And when I received it as a teaching, it came not only in the words; it was all bound up together in the living—in choosing the saying, in showing it to Roshi, in receiving the calligraphy, in his words about it. There was something resonant in the shared recognition—nascent in me, mature in him—that we encounter the Buddha way not by means of our individual purity but through our mutual support. Which is to say, in our aspect as bodhisattvas, we muddle ahead together, whole in our virtues and failings, with no one and nothing left out.

As we at ZCLA were well aware, in matters of purity Maezumi Roshi did not set a high bar. On days off he drank excessively, and though married himself, he occasionally had affairs with female students. For some, his conduct was troubling; for others, not so much. I myself was pretty permissive about such things. I’d been to Woodstock when I was 16; at 18 I’d backpacked around Mexico searching for psychedelic mushrooms and shamans; I’d studied with Trungpa Rinpoche; and for my first couple of years at ZCLA, I’d done my own share of drinking. It was true I was in a monogamous relationship, but I knew that was as much the result of my own ineptitude with women as it was a moral decision. Looking back, I’d say that many of us were naive about the destructive effects of alcoholism and the harm done when sex involves a dramatic imbalance in power relations. I sure was. We most definitely should have been more attentive to the needs of Roshi’s own family.

But even so, I was not looking for a teacher whose conduct was morally pure or exemplary. I found little inspiration in such notions, and I was suspicious of such claims. Even now, I think it is not nearly as hard to follow a strict set of rules as it is to not become rigid or prideful in doing so. I found Maezumi Roshi to be a deeply inspiring guide and teacher, even an example, but not by any conventional measure of his conduct. He had a bottomless love for the tradition of the Buddha way as he had absorbed it through a lifetime of study— it filled his being—and he was completely devoted to sharing with others his dynamic and nuanced appreciation of what had been given him. If you looked at his failings, you’d be partly right, but you’d miss him completely. It was the generosity that was the thing.

You met Maezumi Roshi most fully, I found, in the formal, one-on-one setting that was dokusan. Like his revered dharma ancestor Eihei Dogen, Roshi’s particular genius as a teacher was a matter of subtle appreciation. He might take a phrase from a koan or a passage from Dogen—or just one character from one of those—and work it up and down, backward and forward, and maybe, at some point, you’d feel like something had cracked open and now glowed. You’d feel as if, alongside him, you’d touched upon the world the text carried and, alongside him, had been touched by the line of Zen folk that stood behind him.

Maezumi Roshi was well aware of his failings, at least some of them, and on one occasion he spoke candidly with me about them. The Zen Center was starting to make preparations to host a visit by a large contingent of Burmese monks, including some of the most esteemed meditation masters in Southeast Asia. Because of my background, I had become a kind of unofficial middleman for Theravada affairs at the Zen Center. This particular visit was shaping up to be a highly complicated undertaking, and I went to speak to Roshi about some of the issues that concerned me. In particular, there were more than 200 rules of conduct for Theravada monks, which our future guests would observe strictly, and which the Zen Center community would be committed to honor. But with little connection to the monks or their traditions, hosting them would be new territory for ZCLA; it would be demanding, most likely puzzling, and possibly a source of resentment. I wanted to explain to Roshi the lay of the land and get his take on how best to handle things.

I broached the subject of strict adherence to the rules with a tone that was more than a little apologetic. As I was saying something about how Theravada monks understand their precepts in a highly literal way, Roshi cut me off.

“That can be a good thing,” he said, “I admire that.”

This took me completely by surprise. While the rules of Zen monastic training are indeed strict, these are rules of the training hall. As for the precepts, in Zen—at least in Japanese Zen—the precepts are approached less as rules of conduct than as a source of inspiration and guidance. For Maezumi Roshi to take a stand for a literal interpretation of the precepts was, to say the least, an unexpected turn. And he went on, now with a decidedly rueful note in his voice.

“Maybe if I followed the precepts more strictly I wouldn’t have such poor behavior.”

It was an unvarnished statement of deep disappointment in himself. Roshi was better, and more at home, being strong than not being strong. I don’t know how much his disappointment weighed on him, but I imagine he felt very alone with it. He was more ready to give support than to receive it, and I think we his students preferred that arrangement as well.

I wanted to say something, to somehow give a word or gesture that would convey something—appreciation, support, understanding, or just acknowledgment that I had heard him. But I didn’t. I didn’t know what to do. And then the moment was gone, and I had failed. Things resumed their familiar footing. Roshi kind of shook his head, as though to get rid of the thought, and said, “Anyway, Taido, I want you to take good care of things.”

A measure of disappointment with oneself is not necessarily a bad thing, and it might well be a good thing. We live in the gap between our aspirations and our failure to live up them. One can try to plow ahead through disappointment, but what then? Achieving one’s goals—whether some outward sign of success or an inward victory over one’s shortcomings—may solve one’s disappointment but leave one saddled with arrogance. More likely, any achievement will not be sufficient anyway. The pain that inheres in the gap between what we would like to be and what we are asks less for self-mastery, it seems to me, than it does the support of others.

In the spring of 1984, the Zen Center of Los Angeles went through a wrenching upheaval. By that time, I had been gone from L.A. for a year. I had become disheartened by what I perceived as a growing rot in the community, especially among its leadership. I moved to a branch temple in the Catskills, which had been started a year or two previously by friends from ZCLA. My hope was that distance and a new setting would allow me to keep my connection to the Maezumi Roshi sangha. For a while it worked; then it didn’t.

Maezumi Roshi saw community as central to Zen practice, but he had little interest in the endless messy details that are the stuff of any community’s life. Because they were experimental, the practice centers of the time with a significant residential component—such as ZCLA, San Francisco Zen Center, Trungpa Rinpoche’s Vermont center Karme Chöling, and so forth—were always in the midst of finding their way. They were not quite monasteries, not quite communes, not quite temples, not quite retreat centers, but mixes of all those influences and others. Residents were not quite monastics in any traditional sense, but neither were they traditional layfolk. It was exciting, creative, confusing, and riven with conflict, all mixed together and all needing a lot of care and attention to sort out.

A Buddhist temple in Japan, a Franciscan monastery in Italy, a Methodist church in the United States—each of these subsists in a well-established niche in its society. But for the residential Buddhist meditation communities of the time, no such niche existed. This left them open and innovative, but also shaky and without much foundation. Materially and organizationally, this was obvious; less obvious, but no less significant, was that the belief structures on which these communities rested were delicate and brittle. With just a generation or two of experience behind them, they had had little time to develop the cumulative wisdom of a mature collective enterprise. They were organizations whose collective outlook was shaped, to an inordinate degree, by their founders and just a handful of others.

Maezumi Roshi seemed to prefer to stay with what he knew, and what he knew were the traditional forms of Zen Buddhism and what these forms carried. His focus was the meditation hall, the dokusan room, the lecture platform. He was neither a skilled nor a willing administrator, and he left the hands-on running of the center, for the most part, to his students, especially his senior students. He believed in the kind of hierarchical structure that was familiar to him from his upbringing, and he valued the putting aside of individual disagreement to maintain group harmony, even when that was no more than appearance. He believed in following the chain of command.

Above all other things, Maezumi Roshi was principally concerned with thoroughly training dharma successors. It is not hard to see why he would see things this way. Dharma transmission is at the core of Zen Buddhism; it is one of its defining characteristics. Further, for one focused on transmitting Zen across cultures, the need for well-trained teachers to carry on the work is self-evident. But it was a focus that was not up to the complexity of the situation.

Like all Buddhist traditions, Zen’s transmission narrative freely blends legend, historical fact, and fiction to provide an account that attests to the authority and reliability of its teachings. Understood symbolically, as a myth, it opens up the imagination to apprehensions of what is most valued and meaningful in the tradition. But transmission is also a social institution, and as such, it is subject to the full range of human motivations, virtues, and shortcomings. To elevate the symbolic aspect to literal status and to obscure the social dimension is a mystification, with great potential for harm. At ZCLA, we had little cumulative institutional wisdom to draw on for negotiating the minefield where spiritual meaning met practical reality.

At times Roshi’s way of doing things worked; at others, it didn’t. As the community grew, Roshi grew isolated at the top of the hierarchy he had done so much to create. Seniority in spiritual training added to the stratification of the organizational hierarchy. Often it became conflated with it. Roshi lost touch with the community. Outside the context of formal training—and sometimes even within it—he became remote, opaque. Critical discussion became anathema.

When the Zen Center imploded, I think it was less the result of news of an affair he was having or his drinking—as it is generally said to have been—than it was a blow to so many people’s faith in the integrity of what we were all doing. Roshi’s poor behavior was not new, but the atmosphere of secrecy and manipulation and bullying and deceit—that had grown and festered like a boil ready to burst.

It was not just that Roshi had an affair; it was a matter of the particulars: a hidden affair with a married woman who was a dharma successor and clearly his most favored student at the center. Soon after, it also came out that the most authoritative figure at the center after Roshi, a married man who was also the center’s head administrator, had had a long string of secret affairs of his own. In the eyes of some—and I was certainly one—Roshi had come to rely almost entirely on these two dharma heirs and priests, who mediated between him and the rest of the community and thereby augmented the proper influence they wielded. Dharma succession was one of the main orienting ideas on which ZCLA rested. It is no easy thing to square one’s conviction in following one’s best sense of purpose with the recognition that the project through which one is doing that has grown rotten. In Yeats’s famous words, “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold.”

We had allowed ourselves to betray what was best in ourselves, and that is hard to live with.

I visited ZCLA for a few days just over a year after the upheaval began. The dust had settled, but there was a desolate feeling in the air. The center was drained of its once abundant vitality. Mornings and evenings, the zendo was nearly empty. Many, both residents and non-residents, had quit the community; many others were sorting things out as they prepared for the next step. There was a lot of pain.

Things had not gone so well for me either. A few months after leaving the Catskill center, exhausted and dispirited, I spiraled down into severe depression, the kind William Styron describes as “a veritable howling tempest in the brain.” I made my way to the Bay Area, where I had friends, to ride out the storm and try to regain my bearings. I settled near the San Francisco Zen Center, going to the zendo in the mornings and filling shelves in their grocery store during the day. Mainly, though, I was finding a way to grow through crisis.

I was doing a good deal better but was still shaky when I went to see Maezumi Roshi. I could see he was glad to see me. I think he was surprised. He was seeing the backs of so many, and having a student return to pay greetings and respects might have been something of an oddity. The fact that the student was me might have made it more unexpected. In the year prior to my leaving for New York, things between us had often been strained, with me questioning his judgment and him questioning my loyalty. But I never felt there was a fundamental breach in our relationship. He was always my teacher, even when we didn’t get along.

Roshi’s demeanor was kind of upbeat, but there was something off about it. He seemed ill at ease. I’d never seen him like that before. He spoke openly about his regrets, about so many things he had done wrong, about the damage he’d caused, about how he was trying to do better. He seemed to really mean it, or more accurately, he seemed to really want to mean it. I think, more than anything, he was saying and doing what he thought he needed to in order to restore the community and the practice.

As we spoke, Roshi brought up one of his senior students who had denounced him bitterly. He said he understood her feelings and bore no grudges. Suddenly, though, anger broke through, and while his words said one thing, his emotions said another:

“If she wants to step on my head to lift herself, I’m glad. I don’t need anything back from her. Let her take from me and go ahead. That is how it should be.”

It was just a brief storm, a little lightning, a little thunder, and it was over. But it cleared the sky. He seemed more himself afterward.

There was something Lear-like in his anger. More than that, there was something Lear-like about all that had gone so wrong. A kind of vanity had got the better of Roshi—vanity of talent, vanity of authority. He didn’t recognize the diffidence mixed in with the respect he enjoyed or the ambition behind the flattery he rewarded, and he lost something of what was best in himself. But it was not him alone. We his students lost something of ourselves as well, becoming calculating in our words and affections, more Goneril and Regan than Cordelia.

But what soul is without its bit of Lear? Vain and foolish, out on the heath, howling at the storm, needing others to restore us to ourselves.

We are the howl. We are the storm.

Sometimes we fail each other so thoroughly that the only way we can find to support each other is by hurting each other. Still, without the help of others, we’re surely lost. Over the years since, it seems, from my place of remove, that the Maezumi sangha, now far-flung, has done much to restore itself. And all of us—we followers of the Buddha way—have had no shortage of error and foolishness to learn from as we’ve muddled ahead together.

We are the clod of earth. We are the mud.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.