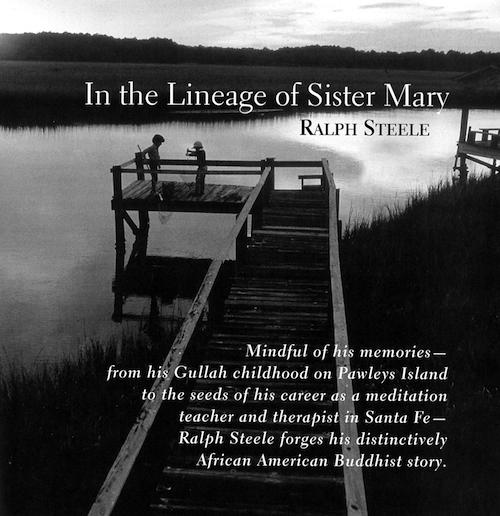

I was born on Pawleys Island. The real island, off the coast of South Carolina, was all white people. No blacks were allowed. We lived in the swamps, in the woods on the opposite shore. But we called it Pawleys Island anyway. Our community was made up of villes—Parkersville, Maryville, Plantersville—like African villages.

We spoke Gullah, a mixture of African languages, French, and English, and our customs, like our speech, contained whole pieces of Africa that had made the long journey over to the slave ports. We had no phones and no doctors. We did have a TV, but the only thing we watched were the fights and The Little Rascals. We lived off the land.

If an ax handle broke, we went into the woods and cut a new one. We were healed the old way, with herbs and prayer. The elder churchwomen were all called “Sister,” and the men were called “Baba.” The church was the hub of the community. When we were getting a haircut on Saturday, the men who sang in the choir on Sunday were singing their spiritual songs. Their voices would vibrate your bones. Reverence was in every daily activity, whether plowing the fields or getting a haircut.

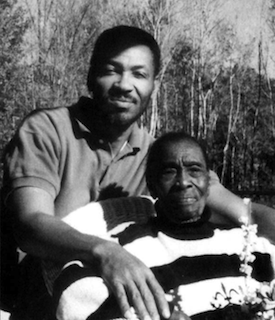

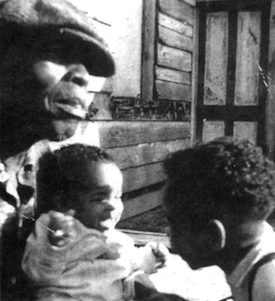

My brother Jimmy and I lived with our grandmother, Sister Mary, and her husband, Baba James. Our mother, during most of our childhood, was working in Myrtle Beach, trying to make ends meet. All I remember of my dad is him pushing me in a swing. And the funeral, where I stood at the head of his grave, after he was killed in a car accident.

Everyone knew that Sister Mary was a different kind of person. She had a garden that was quite unusual: everything was huge, irregular. It was like something out of a fairy tale. As my brother and I worked pulling weeds for Sister Mary, she would sing and pray. Those vegetables were brought up on songs like “Precious Lord” and the vibrations that woman put into the soil as she tended it. One ear of corn would be sixteen inches long. One leaf of collard greens might be two to three feet in length. Tomatoes were like grapefruits. When people drove by, they would often stop just to look, or take pictures. She also had a magnificent flower garden. And she tended the yard like a Zen master. It was raked every day, not just the garden but the path you walked on. That was one of my jobs.

Sister Mary was my earliest lesson in what we call mindfulness.

I remember when the chain gangs would come to clean the road. You could hear them singing and the sounds of weeds being cut. They’d come right up to the house, all African Americans, of course, except for one guy in sunglasses with a shotgun draped over his arms. Each man had a long-handled ax. My younger brother Jimmy and I would hide in the bushes and watch. Sister Mary would walk out the front door with a pitcher of lemonade and a cup attached to it with a string. In her other hand she would have a plate of fresh cornbread. The man with the gun would lock it in place and raise it disapprovingly, and Sister Mary would walk right past the man as if he didn’t exist. Completely focused on that moment, she would go to each man with a drink and some bread. Her job was to console them. Sister Mary would forgive them for what they had done. Some of the men would have tears in their eyes.

Finally, she would walk up to the man with the gun and ask if he’d like some lemonade and some bread. He always said no. He missed her blessing. Then the men would leave, someone would start up a tune, and the men would begin singing and swinging their axes in unison. It was like a dance moving down the road.

My brother and I always went out into the road and shot marbles after they left.

When I was thirteen, we went from Pawleys Island to Montgomery, Alabama, for a year. And then to Bakersfield, California. Out of the blue, I was in an all-white school.

In Buddhism, suffering is part of inhabiting a human body. When we encounter belief systems that seem unrealistic, we’re apt to strike out against them. Racism itself is like lightning in pine trees. The arrow goes back and forth; you don’t know what caused which one to strike the other. Who is the lightning and who is the pine tree? Having left the serenity of Pawleys Island behind, I found myself in the storm rather than observing it.

In Bakersfield, I got a good taste of racism. Once I was cornered in a bathroom by a bunch of guys who wanted to jump me. Teachers would ridicule me, make fun of my language and so forth. Before long, in a confrontation, I would start shaking. Even if we weren’t talking, I’d shake.

Then the Air Force transferred my stepdad to Japan. It was such a big shift for me that even today I can hardly sort it out.

Out of maybe eight hundred kids, there were maybe fifteen or twenty blacks in the American school. I began playing football and basketball. But a lot of the time I just tried to make myself invisible.

At an interschool tournament, the coach came into the locker room and said, “Steele, you’re not suiting up.” There had been a fight and he blamed me. Some kid had got burned in the eye with a cigarette. And they said it was my fault.

I said, “Coach, I don’t even smoke.”

He didn’t believe me and I couldn’t play. And I was shocked. I didn’t really know how to handle it, so I quit. I had been hoping for a career in sports, and it had looked like a good ticket into college. But I gave it all up.

That day, I just jumped on a train instead of going to my sixth-period class and wound up back at the base, at the gym. Upstairs, I saw about twenty guys in martial arts uniforms. A little tiny man was in charge. When I walked into the room, the teacher was at the head of the row of guys farthest from me. He had a bamboo stick, strips of bamboo bundled together. Next thing I knew, that teacher had flown across all the rows and was standing in front of me—he had somehow sailed over to hit one of the students beside me. I could’t believe it. How did he get all the way over here?

After the class, I asked him if I could join. Through an interpreter, he said that I had to take judo first. I needed to learn how to fall.

When I came back, he let me in the class. It was called karate: fifty percent hands and fifty percent feet. During one session, he called me over, slapping himself in the ass: “Steele!” He faced off at me. I went after him, and the next thing I knew, I was on the floor. He hit his ass again and I got up. We kept going through the same routine. After a few times—and he knew this was going to happen—I got raving mad. I just charged at him. Boom! I was on the floor. If I hadn’t taken judo, I would have broken all my bones.

Then I felt like giving up. He knew it was coming. He bowed. And I bowed. And from that moment on, I had a real teacher. I saw him do the same thing later to another man, a weight lifter who looked like the Hulk. Each time this huge man would go like gangbusters at this tiny teacher, he would end up high in the air, and the teacher would cradle his head as he came crashing down. In this simple way, my teacher broke down this man’s ego, so he could learn something new.

In meditation practice, this is what I call “Keep your sweet ass on the cushion.” It’s a form of surrender. It’s not becoming somebody special, but becoming opened.

My work with this man was like all-out training. Sometimes, I limped home. My mother asked why I kept going back for more punishment. The reason was: Because of my teacher’s kindness. And because of his humility. I saw a mixture of true human feeling and discipline.

I hadn’t met anyone with those qualities since Sister Mary and Baba James. Yet I was so young, I don’t even remember his name.

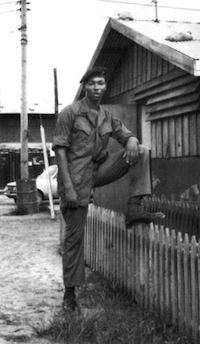

My problem with drugs, with heroin, began in Vietnam. It first happened when I was put in the hospital.

The ward, when I first got there, was pretty funny. It was full of brothers, playing cards. Like one big family. One evening we were all going to a movie. And guys were saying to me, “Ralph, make sure you get a wheelchair.” I wondered, “Why should I get a wheelchair? I can walk just fine.” They said, “No, get a wheelchair.”

I found a parking place and the movie started. Pretty soon, somebody passed me a film canister. It was filled with white powder. There was a small spoon. I had watched the others snort from it. So I did the same thing. It came around twice. It turned out that the reason we all needed wheelchairs was because we’d all be so damn high we couldn’t walk.

That was the first time I ever used heroin. We called it Riding the Horse. From that point on, instead of drinking on the days we weren’t flying the helicopter, I would just smoke marijuana and snort heroin. We had our own flight surgeon, so he could always test the stuff for us. Heroin and alcohol became part of the coping process. They helped keep you sane.

At the end of my tour of duty, I just waited around the base for two days. At last, the moment came to board the plane. As we walked on, they were loading bodies into the baggage compartment. When the wheels left the ground, there was a loud cheer. Tears came out of our eyes: This is for real! We’re going home!

In Fort Dix, New Jersey, my knees hit the concrete and I bent down and kissed it. A lot of other guys did the same thing.

I headed for Kansas City, where my parents were living. On the plane, I started to get the sweats. I was shaking. I didn’t know what was going on. A doctor on the plane thought that maybe I had malaria.

I didn’t realize I was an addict. I thought I’d just go home to my mother’s house, get some things together, then report to my home base. We lived in an all-white neighborhood close to the air force base where my stepfather was assigned. My mother came down the stairs on the second day I was home. I was sleeping, but in an instant I was on my feet, alert, and careful. She was startled and I was startled.

She said: “You’re not the son I raised. I’m going to have to get to know you all over again.”

I was in another zone. The way I got out of bed, I was ready for combat. I was thinking about seeing a doctor because I’d had the shakes on the plane. But like a good soldier, I decided to get a haircut first.

So I drove over to this barbershop. There were two barbers and three guys waiting. I sat down. The barber said, “Can I help you?”

When he said that, I knew something was wrong. This wasn’t going to work out. I told him I was there to get a haircut.

“We don’t cut your kind of hair,” said the barber.

When the other guys heard that, they were struck. One of them said, “If you don’t cut his hair, you don’t cut mine.” Those white guys walked out. I didn’t say anything. I was just being cool. I got back in the car. By the time I got home, I was shaking like crazy. I was thinking about going back and driving my car through the window.

You learn through meditation that pain will always wake you up to the fact that everything is impermanent. Though I didn’t understand it at the time, that was happening to me in Kansas City. Just because I had been in a war, that didn’t change the relationship between lightning and pine trees.

I called my mom at work. I told her what had happened and she got me to calm down. I went over to the base and got some cash. Then I went straight to the liquor store. I went home and got drunk to where I could go to sleep. For the next few days I hung around the house. I tried to look up some friends. A few were in jail, some were dead. Then I left and went to my home base in Savannah.

Our company was responsible for repairing aviation equipment. But I was still shaking all the time. Sometimes it would knock me off the bench. I kept trying to find out what was happening. I had quit drinking when I got to the base. So the shakes were taking over.

I went to the Army psychiatrist. He asked me: “Have you ever had sexual feelings toward your mother?” This really pissed me off. I threw my pen against the wall and left. Then I went to a bar. There was a brother at the bar, a civilian, and I told him about the shakes. He put it very simply: “You got the jones.”

I was withdrawing from heroin. I was a junkie.

Desire is one of the three forces of delusion seen by the Buddha during his quest to understand the nature of suffering. When your awareness or behavior is out of control because of desire, you might as well jump into a hornet’s nest. Who knows how many times you’ll get stung? But until my addiction, I had no real understanding of how desire creates suffering. I had no ability to investigate the quality of my own perception, to be mindful before taking action.

The methadone program the military put me on was a bad strike against me. I decided to make my own program to get off the drugs and the five packs of cigarettes a day. I had to face my addiction.

It was martial arts and Baba James and Sister Mary that had given me the training to overcome and release the suffering. It took three months.

I took catechism at the age of twenty-two, so I could get into Mass and go to a Catholic retreat center down in Big Sur to study with the monks there. I had started work on a second undergraduate degree at the University of California in religious studies. That was when I began meeting dharma teachers. Somebody had told me that Lama Thubten Yeshe was scheduled to give a talk on Buddhism at one of the colleges on the Santa Cruz campus.

They had told me to give him a flower, and I wouldn’t do that because, I said, “Men don’t give men flowers.” I was still very military at the time. I remember walking toward Oakes College, a beautiful building that was designed to blend into the woods. I was about fifty yards from the door I had planned to enter. All of a sudden, I noticed that I had stepped into a field of energy that made me stop. It felt as if the air were dense—my body had vibrational sensations all over.

When I settled down, I continued my walk to the classroom. I reached the double door and stepped inside. I found myself inside an auditorium-like space, looking straight down the rows of seats at Lama Thubten Yeshe. He was sitting on a platform without a chair.

And at the same time, he looked at me, and he smiled. He knew I had stepped into his energy field—and that it was simply his presence. I slowly found a seat and began to listen to this brother rap about awareness and concentration. This was my first teaching of the dharma.

I spent a long time training with Lama Yeshe, Stephen Levine, and others in Santa Cruz. The most important thing I got in dharma in that period was working with the pain in my heart, softening the heart. Stephen and I would have this thing where we would say, “Don’t move”—it doesn’t matter what’s going on, you just don’t move. It was intense. You were on fire.

I had flashbacks for many years: my Vietnam experiences, not to mention what had been going on all around me in America before I even went overseas—Martin Luther King’s death, race riots. There were times when simply being on this planet seemed like a whole bundle of pain, anger, and anguish. But Stephen was so clear about helping someone to be in that fire, to let go. And if you sit in the fire, grace will come—it will eventually come, a cooling effect. He helped me to sit like a mountain.

Nowadays, in my therapy practice in Santa Fe, I begin each relationship with a new client by asking myself: How did this person unintentionally create the situation that brought her to the office? Why is she out of harmony with her body, speech, and mind? It took many years—maybe lifetimes—for this person to be in my presence. So what brought her to me?

What insight meditation teaches people is this: Underneath their speech and their own honest effort in doing what they think is right, there is this unintentional conditioning that has been causing them to constantly fuel the fire, to constantly create more suffering and dissatisfaction for themselves. This conditioning really comes from our own humanness. It comes from being in the human body, being raised in a particular culture, coming up a certain way to not really listen to your heart. To not ask for forgiveness for yourself, as well as for others. We condition each other, but mainly we condition ourselves.

Doubt and restlessness were what moved me along the path. Then I began to see my mind’s state come up with the hatred, greed, and delusion. My own racism would come up. That is one thing I believe—that everyone has something against another culture. Once they can recognize and drop that, they’ve learned something. All this stuff comes up, and it’s what makes me work my practice.

Still, even with that recognition, when I open my eyes and walk around, there are times I don’t really feel comfortable. Even my partner notices. I’ve taken her back to my family several times, and she’s said: “The only time you are really comfortable is when you are at home.” You can’t put any ego trips on the folks who changed your diapers. You really get put in your place quick. But society makes you play a lot of mind games—some intentional, some not. So learning the practice helps you to canoe in this ocean we live in.

I know people of color are not afraid to step forward in this. But it is difficult because it is predominantly European American people at Buddhist retreats. The anger and resentment are a part of our common history.

Nevertheless, the practice is not about history. It’s about how to cultivate the immediate present. Right here in the present is where grace comes down. That’s without any dogma attached to it. For people not of color, I hope it gives them insight to bring someone to a retreat. And with regard to teachers, to begin really incorporating the language of diversification as they teach the dharma.

European Americans have almost forgotten that the Buddha was a person of color.

Seven years after I had moved to New Mexico, I returned to Santa Cruz. My final day there, I learned that Lama Thubten Yeshe had died and that a ceremony was to take place in a few hours.

I went to Boulder Creek, up in the mountains, where he had had a meditation center built. I arrived at a building and ran toward it, thinking that everyone must be inside because of all of the cars that were parked there. I stopped just long enough outside the door to calm down so I wouldn’t look unusual. As the only African American ever at these Buddhist gatherings, I had become aware that there was no need to attract any more attention.

Then I walked in. Nobody was inside.

I left through another door in the side of the building. Outside, there was a black van whose side doors were still a few inches from closing. When they closed, the van began to move. I walked behind it and joined a crowd of about fifty to a hundred people.

It was a slow meditation walk up the road. We came to an altar in the redwoods, next to a pagoda, cylinder-shaped, of mud and clay. The door of the van opened and my eyes quickly fixed on what was inside: Lama Thubten Yeshe, sitting in meditation posture. A few men lifted him up and carried him to the partially built pagoda. Several redwood logs were placed in the cylinder around the body. They continued building the mud wall up, and as it got higher, the cylinder shape got smaller.

The fire was lit by placing a stick with a flame in a hole at the bottom of the pagoda. Prayers continued, and I heard the fire inside begin to roar like a lion and the redwood make popping sounds.

I noticed a flower lying on the ground. I reached down with my hand, and as I picked it up, a pair of shoes came into view. I glanced up and a lama with a long white beard stopped and looked at me as if to say: What are you going to do?

I placed the flower on the altar. The lama’s eyes and face lit up like a full moon and together we bowed to the pagoda.

Racism is like lightning in pine trees. But who is the lightning and who is the pine tree?

When your awareness or behavior is out of control because of desire, you might as well jump into a hornet’s nest. But until my addiction, I had no real understanding of how desire creates suffering.

If you sit in the fire, grace will come—it will eventually come, a cooling effect.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.