Life, the great destroyer, is the source of all.

Compassion, rejecting nothing, has never known fear;

Here is Yamantaka, the Conqueror of Death,

Dwelling inseparably in the center of the gold cloud-palace of the senses:

This is the supreme protection.

Like a worn and towering sandstone sculpture that a traveler in the remote steppes might come upon, the life story of Lubsan Samdan Tsydenov is strangely imposing, even monumental. Its sources are difficult to access and not easy to verify. He emerges from a confused and violent past, and he seems more a heroic figure in a folktale—like an emanation of the epic king Gesar, say—than an actual historical person. But it is undisputed that he was destined to be a monk, that he lived as a Buddhist teacher, that he became a king, and that, finally, he disappeared into the brutal chaos of the early 20th century.

To begin, scholars agree that Tsydenov was born in 1850 in southern Buryatia near Lake Baikal. Buryatia is a South Central Siberian territory bordered by Russia to the north, Mongolia to the south, and Lake Baikal to the west. It is the homeland of several Buryat Mongol tribes, and has, since the 18th century, been the northernmost territory to adopt Tibetan Buddhist practices.

Even as a small boy, Tsydenov had a reputation for stubbornness. People still tell the story about his determination. One spring morning he joined a group of children competing to see how far they could throw stones into a broad stream. He was not the best, but long after the others had gone home Tsydenov remained, pitching one stone after another as far as he could. He continued through the rest of the day and well into the evening. By the time his mother came to find him, the stream was dammed and a small lake had begun to form. The lake remains today and, even if the man himself has been forgotten, is still called Samdan Lake.

When he was 10, his parents sent him to Kudun Datsan, the nearby Gelugpa monastery, where, it is said, his concentration in study and in meditation practice was more singleminded than anyone had ever seen. Once the abbot sent him to bring a mare back from a distant pasture. He was preoccupied with reflecting on the nature of suffering and returned hours later, empty-handed. A farmer had seen Tsydenov walk right past the animal, but when the abbot asked Tsydenov what had happened, Tsydenov replied: “I went to the pasture, as you told me, but there is no horse.” Some thought that this reply was evidence of his strict discipline, while others found in it an echo of shunyata, or emptiness.

Throughout the following years, Tsydenov’s meditation practice was unwavering, and he remained an omnivorous scholar. Many accounts assert that he studied Western philosophy when he could find texts, and he sought out traveling Nyingma lamas, followers of the earliest Buddhist teaching in Tibet, for teachings. In this period, Tsydenov also became a disciple of the 13th Jayagsy Gegen Tulku, abbot of the great Kumbum Monastery in Tibet. Tsydenov was 35 when, after years of study, he passed the rigorous tests for the title of geshe, the equivalent of a philosophy doctorate. At that point he became an official part of the Buddhist hierarchy in Buryatia.

Jayagsy Tulku made several visits to Buryatia and gave Tsydenov special oral instructions on the practice of Yamantaka, conqueror of the Lord of Death. The two also discussed at great length the future of Buddhist institutions. According to notebooks of people who had spoken with him, Tsydenov believed that the 20th century would bring unparalleled upheavals and that the monastic way of life would no longer be able to ensure the continuity of the Buddha’s teachings. He proposed instead to establish a community of lay practitioners who would focus on older forms of tantric practice. This was the only way, as he later wrote, that the buddhadharma could survive and even expand to the West. Despite what many have characterized as Tsydenov’s aloof manner, his clarity of mind and absolute devotion earned the admiration and trust of the Buddhist community.

It is true, however, that they sometimes found their new geshe alarming. Once, a wealthy layman requested Tsydenov to perform an offering to Dorje Legpa, a powerful protector, particularly of manufacturers and merchants, frequently shown riding on a goat, wearing a gold helmet and holding a hammer and bellows. The layman had unfurled a thangka [scroll painting] of the deity above the shrine and set out rows of ritual offering cakes before it. When Tsydenov arrived, he took down the thangka and rolled it up, then shredded the offerings and scattered them, saying, “Surely, this is more than enough for an ordinary blacksmith.” From this, people saw that for Tsydenov, the world of deities and the world of human beings were not so very separate.

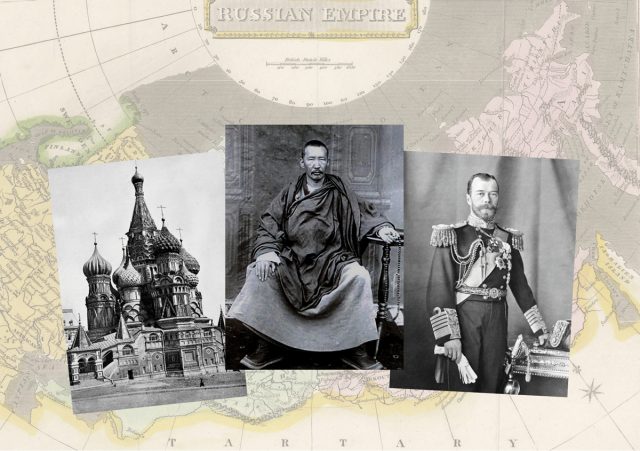

When the abbot of Kudun died, many wanted Tsydenov to be appointed to the position. A clique who resented Tsydenov’s gifts and reputation prevented this. He was, however, invited to be one of a party of Buryat nobles and priests invited to visit Moscow to attend the coronation of Nicholas II in May 1896. From scattered accounts, it is possible to infer what followed. The Buryat delegation attended the coronation at the cathedral of the Assumption Cathedral in Moscow. A later audience took place near St. Petersburg in the long gilded hall of the imperial palace at Tsarskoye Selo. The guests felt engulfed in the glow of gold plasterwork. Nothing in the way they lived prepared them for the brilliance of the churches and the palaces. They were dazzled amid mirrors blazing as if lit from within. It was like being in the center of a sun. The visitors from the remote Siberian steppes had never imagined such splendor and on such a scale.

A court functionary in black banged his ivory staff. Guards in silver breastplates snapped to attention, and Nicholas, in a uniform of deep red with gold braid, entered quickly and sat on his silver throne. Everyone was overcome with awe. As instructed, they all bowed low. Tsydenov, however, did not. He stood, stared at the czar and nodded respectfully. Courtiers and visitors were equally aghast. Tsydenov later maintained that his vows and the Vinaya, the Buddhist monastic code, did not permit a monk to bow to a secular ruler. The head of the delegation made anxious excuses to court functionaries, saying that Tsydenov had been stunned by the sight of the czar and did not know what he was doing. The apology was accepted.

While he was in St. Petersburg and Moscow, Tsydenov met also with Western intellectuals and orientalists, from whom he obtained books on Western philosophy and political theory. But when he returned from St. Petersburg, he did not stay long at Kunbum Monastery. “A monastery is also samsara,” he said. Accompanied by a few students, he withdrew to the remote village of Soorkhoi and remained there on retreat for more than 20 years.

After the coronation in the early summer of 1896, most surprisingly, Tsydenov sent a poem, written in Tibetan, to the czar. It was a long dream-vision of a transcendent ruler in a celestial realm of unimaginable opulence and beauty. Here Nicholas II was seen both as an enlightened monarch, or chakravartin, and an emanation of the deity White Tara, who spreads peace and wisdom just as a buddha’s wisdom permeates his world. The czarina was presented in the poem as a divine consort, with attendants who lived to fulfill the czar’s mission in the world. And so, even if Tsydenov had not bowed to the czar, now we find him writing of Russian cities as if they were filled with the magical beauties of a pure land, and of Nicholas II and his court as worldly deities. Perhaps he sensed how much the world would change, and how the imperial order embodied virtues that would be swept away.

Here is a part of this ode:

Like the full moon amid stars,

The Czar Nicholas, the radiant Lord, blesses the minds

of all his subjects.

As he emerges in the sky with his radiant consort,

He embodies the fulfillment of all the world’s longings.I look up and the sky opens,

And just as the still expanse of the sea

Is suddenly ornamented with shining ripples,

It seems my body is wrapped in golden cloth.

The hair on my skin rises and shivers.

For a long time, I cannot move.

Then I make three prostrations.

I offer the symbols for an enduring life:

A white silk scarf, a jeweled mandala, a statue of

Amitayus, Embodiment of Life and Light.

I pray:

May this ruler forever entrance our minds,

Forever dispel the darkness of disorder and chaos.

May he sit in splendor on his diamond throne.May the pure land of imperial rule

Pervade all time.

Without a holy ruler,

How can humankind know peace?

Please protect us from the madness of the worldMay this song, written down under the light of two

electric bulbs, bring all-pervasive purity and perfect

bliss to every sentient being.

Tsydenov and his followers remained in determined seclusion, but from the beginning of the new century, the rest of the world careened into chaos. All across Russia, in the first decade of the 20th century, people rose up against the crown. At the beginning of the second decade, thousands of years of imperial rule ended in China. In the midst of encroaching turmoil, Tsydenov began to study the most ancient tantras, and though still on retreat, he was asked to serve as abbot of Kudun Datsan. He accepted the responsibility but stayed in Soorkhoi, while his students looked after the day-to-day management of the monastery. He was more than happy to surrender both title and work some years later when the Buddhist hierarchy demanded it. Everyone had heard that the provisional government in St. Petersburg was failing and that hundreds of thousands of Russians were being killed on the battlefields of Europe. While the Red armies campaigned in western Russia, the White armies crisscrossed Central Asia. Tsydenov was committed to training practitioners who could endure life in such a world.

Foremost among his students were Dorje Gabzhi Badmaev, Tsydenov’s main disciple and assistant for many years, and his stepson, Bidia Dandarovitch Dandaron. Born on December 28, 1914, Dandaron was 3 years old when the czar was forced to abdicate in 1917. His education had begun when he was very young, and there is no doubt that he was aware of the collapsing world around him as the Cossack army of Ataman Grigory Semyonov moved into Buryatia. Semyonov’s troops, like all the armies of the time, lived by stealing from farmers, herdsmen, merchants, and peasants. This army was worse: they were murderers, rapists, and thieves. Semyonov finally began to tame them, allied himself with Japanese troops near Manchuria, and took control of local governments through their preexisting dumas [assemblies].

Under his rule, Mongolia, Siberia, and Buryatia established semi-autonomous domains. Nonetheless, in 1918 the Czech Legion was on the verge of taking control of the Trans-Siberian Railway, while Baron Sternberg von Ungarn’s army was moving to establish a Pan-Mongolian Empire. In the autumn, Semyonov decided to expand his forces by drafting young Buryat men.

It was at this point that Lubsan Samden Tsydenov did something for which, if he is known at all, he is still remembered. All around him, the world was collapsing into war as armies sought territory, wealth, and power. In the midst of this spreading violence and horror, he took advantage of both the Soviet proclamation of land reform and the inability of the Red Army to move east.

Then, at the request of the Khori clan of the Buryats—some 13,000 families—Tsydenov assumed the role and title of chakravartin, a dharma king, and proclaimed the establishment of a Buddhist kingdom, a realm that would exist entirely in accord with the Buddhist teachings. He said: “He who does not wish to fight, since fighting is contrary to the Buddha’s law, let him come to me and be a subject in this kingdom.”

He wrote some years after his creation of this kingdom:

I really am a king of dharma of past, present, and future. This authority has been conferred on me by the spontaneous wisdom of the awakened state. It is my responsibility to save my subjects. We are bound together by the vow of nonviolence and by other vows to uphold the purity of life itself. Accordingly, no one may kill or serve in the army. There will be no army. Establishing this Buddhist state, I follow the principle of combining the religious and secular principles of government where authority is a union of those two. To rule is to accept the reality of life and death.

Tsydenov created a state modeled on both the rule of the Dalai Lama in Tibet and on Western principles of elective democracy. All government positions other than that of the chakravartin ruler were elected by secret ballot from among those who had been elected to the constituent assembly. He ordered a commission to create the government and other institutions of the new state and appointed Badmaev as his successor. This government functioned simultaneously with the apparatus of Ataman Semyonov’s Russia Eastern Outskirts. The citizens were henceforth called balagats. Some, even after the fall of the kingdom, continued to live and practice tantra as lay people. All would be imprisoned or dead by 1935.

In early May 1919, a week after this Buddhist state was formally established, agents of Semyonov’s police arrested Tsydenov and nine members of his government. They were released in a month after Tsydenov formally agreed to cooperate with Semyonov’s government. This happened three more times in the same year. Each time, Tsydenov’s release was taken as a sign of his magical invulnerability. Throughout the year Tsydenov and his disciples taught, practiced, and administered his kingdom to the great contentment of his subjects. Even the death of his appointed successor, Badmaev, did not interrupt the progress of the kingdom.

The ancestors have shown the unmistaken path.

Following them,

The Chakravartin’s heart has broken open in the

emptiness of space.

In the openness of the heart,

He dwells in the hidden expanse.

It was quite miraculous that, in such a tumultuous, hopeless, and violent climate, Tsydenov’s Buddhist kingdom managed for a year to flourish and protect tens of thousands of women, children, and men adhering to principles of nonviolence. To create something like this, if only for a moment, was extraordinary. The Red Army under General Tukhachev began to overwhelm the various White armies. Regional Bolshevik groups began to establish local councils ruling on behalf of the supreme Soviet. In May of 1920, Tsdenov had again been arrested by Semyonov’s agents and jailed in Verkhneudinsk. Six months later, Semyonov was driven from all the Buryat lands by the Red Army. Bolshevik forces gradually conquered all of the Russian far east. So by the end of 1920, the Red Army controlled all the territory of what had been Tsydenov’s kingdom, and Tsydenov, still imprisoned in Verkhneudinsk, was now a captive of the Soviets. At this time, he wrote a letter proclaiming that the 7-year-old Dandaron would be his successor as chakravartin.

Related: From Russia with Love and Russia’s Buddhist Revival

In 1922, the Cheka (Soviet secret police) moved Tsydenov from Verkhneudinsk to Novosibirsk. There he was isolated from contact with family, followers, and friends. He was not heard from again. According to an official statement, Tsydenov died in a military hospital in Novosibirsk on May 16, 1922. However, some said he was later taken to an unnamed labor camp farther north. In a third account, a man named Tsygan told V. Montlevich that in 1924 he had seen Tsydenov in the railway station in Verkhneudinsk. Tsydenov was dressed in an elegant European pin-striped suit. When Tsygan greeted him and asked what he was doing, Tsydenov shook his hand and said that he was “going to Italy.”

By the 1930s, all 44 Buddhist monasteries in Buryatia had been shut or destroyed. Their lamas—15,000 to 17,000 of them—had been killed or imprisoned. Some 45,000 Buryats, considered to be rebels, had been murdered. Traditional Buryat culture was erased. Tsydenov’s heir, Bidye Dandaron, spent the rest of his life in and out of forced labor camps in the Gulag system. It is said that throughout his imprisonment he never stopped trying to find Tsydenov. He asked prisoners and prison guards if they had heard of him. Whether he knew his questions were in vain, no one can say, but clearly Dandaron did not think that even if the search was futile this was a reason to stop. But for the rest of the world, Tsydenov was a name written in some moldering files, a tale recounted by aging storytellers in a string of curious episodes, images in a few grainy photographs, the name of one who was momentarily a protector and, if fleetingly, a true dharma king.

♦

The next installment of Ancestors in the Fall 2018 issue will cover the life of Bidye Dandaron, Tsydenov’s heir.

Except for Tsydenov’s ode on p. 53, poems by Douglas Penick.

This article relies particularly upon the work of two scholars, Nikolay Tsyrempilovand and Ven. Vello Vaartinou.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.