This book is, first and foremost, a labor of love. A cherished family heirloom at risk of loss in the Tibetan diaspora is passed from hand to hand and eventually finds its way to the United States. There, a fortuitous meeting between a member of a distinguished Tibetan family and a young American graduate student evolves into this book: a reproduction of one of the rare complete sets of portraits of the eighty-four mahasiddhas, a traditional grouping of Indian mystics from the 8th through 12th centuries whose biographies are legend in Tibetan Buddhism.

That young graduate was Donald S. Lopez Jr., today a well-known professor and expert in Indian and Tibetan Buddhism. His comprehensive introduction includes a brief summary of Vajrayana Buddhism; an appreciation of the mystics who became known as the eighty-four mahasiddhas; a commentary on the paintings that discusses their stylistic elements and how they were made; a brief history of the family who commissioned these paintings in 1935; and an account of how Lopez came to publish them in book form after they were brought from Tibet to India in the 1950s.

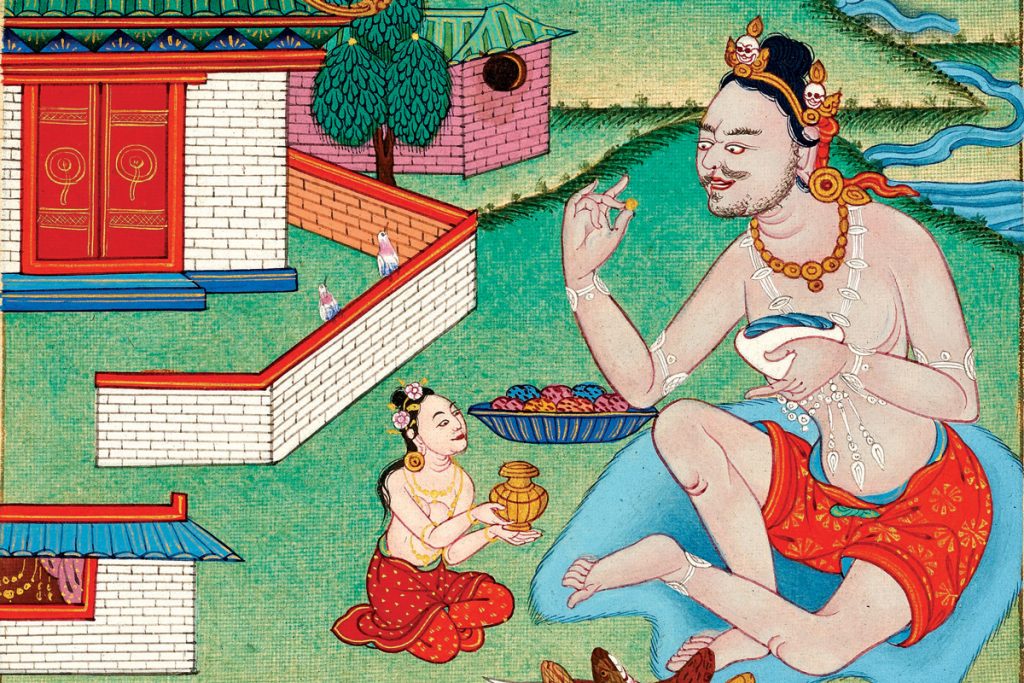

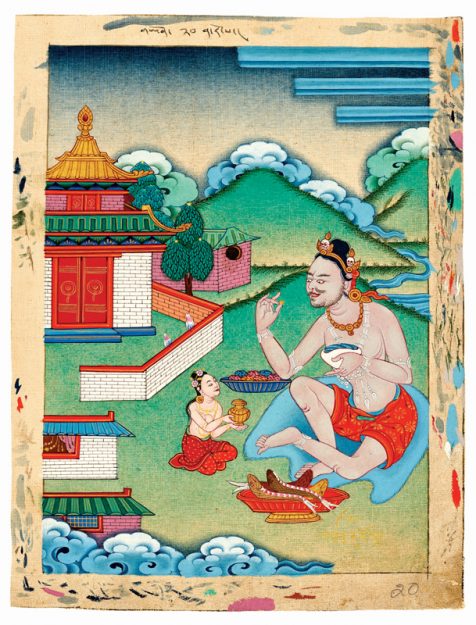

The main part of the book is devoted to the paintings themselves—small pieces, almost miniatures, by an unknown master artist that were brought out of Tibet before they could be mounted in traditional brocade frames. Each painting is accompanied by a brief biography of the mahasiddha, a description of the painting itself, and an even briefer excerpt from a painting guide written by the great 17th-century scholar-mystic Taranatha.

What is a mahasiddha, then? In Indian Buddhism, what we now call Vajrayana evolved out of the sorcery cults of medieval India. Dates are uncertain, but some practices and deities of Vajrayana can be traced back to at least the 5th or 6th century CE. A practitioner who developed actual powers (Lopez describes these powers in his introduction) was known as a siddha (a person of power), a term we could reasonably translate as “sorcerer” or “magician.” In Indian culture, the prefix maha, meaning “great,” was often applied to indicate that a person or teaching or work had moved into the realm of mysticism. Gandhi, for instance, was referred to as Mahatma, or “Great Soul,” and mahakaruna indicates a mystical compassion, in contrast to karuna, compassion that operates more in the conventional sense of that word. Thus the mahasiddhas were great sorcerers, individuals who had mastered mystical under-standing. By mystical understanding, I mean the ability to experience and relate to the mystery of life without relying on the conceptual mind.

Lopez touches only briefly on this mystical understanding; his main focus is on the paintings themselves. The interested reader will need to consult one or more of the several English translations of the key source text for all these stories, James Robinson’s Buddha’s Lions, for instance, or Keith Dowman’s Legends of the Mahasiddhas. The latter book includes Robert Beer’s contemporary representations of the eighty-four mahasiddhas, which may make for an interesting comparison with the traditional representations in Lopez’s book.

Seeing the Sacred in Samsara: An Illustrated Guide to the Eighty-Four Mahasiddhas

by Donald S. Lopez Jr. Shambhala Publications, May 2019. 232 pp., $29.95, cloth

The key significance of the eighty-four mahasiddhas is that that they represent the possibility of awakening regardless of your socioeconomic status, or, for that matter, how you live your life. Royalty, monastics, tradespeople, craft workers, men and women from all walks of life are represented here. In addition, each story illustrates how mystical understanding is found in the nitty-gritty of life, how the clarity and peace of awakening is found in your own experience and reactivity, whether you are a liar, a glutton, a thief, or a prince. Hence the title of the book: awakening (the sacred) is to be found in your actual experience of life, with all its reactivity and confusion (samsara).

Related: Tantric Trailblazers: A gathering of mystics

Each story has essentially the same structure. An individual immersed in ordinary life encounters a teacher. The teacher awakens a seed of mystical experience (through empowerment) and provides instruction. After a lengthy period of practice, the individual attains mastery and is able to display his or her attainment. Thus, each story functions on three levels: a historical account, an exemplary tale, and an allegory of awakening.

But the real subject matter of this book is the art, the exquisite paintings that are beautifully reproduced here. Readers or viewers may find that when they leaf through these pages, the combination of traditional stylization, the repeated iconographic elements, and the range of individuals from so many different backgrounds awakens something ineffable, yet powerful; they, in turn, are moved to explore what each of these individuals chose to explore.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.