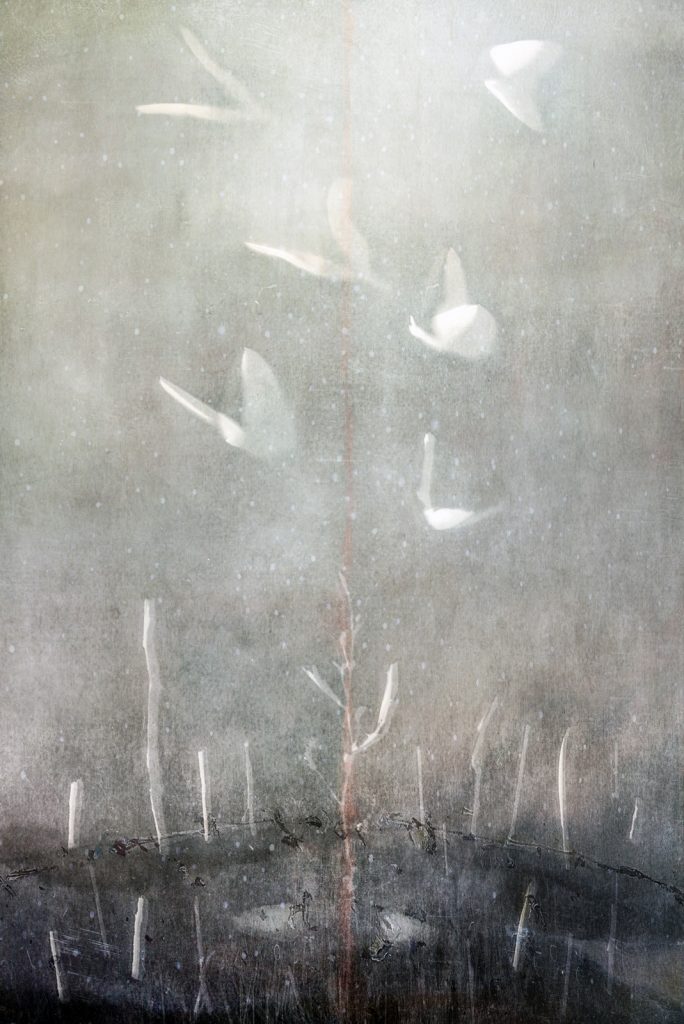

O Kali,

Star-shimmering night-body of time.

With obsidian mirror-eyes radiating an infinite void,

We cannot escape meeting you face to face.

You are the darkness that devours the waking world.

You swallow us as we sleep,

Leaving fragmentary fleeting dreams devoid of place.

O Kali,

You are the last and first moment of yearning, poetry, and love.

[1]

For most of us these days, our world is the world of buying and selling, for sale and sold, bought and owned. We must continuously evaluate the relative advantages of transactions. Our public lives shuttle between work, where we are bought by the hour, and entertainments, which we purchase in varying increments of time. In the incessant clamor of advertising, exhortations to purchase, to possess, it is hard to find a path to authentic inspiration. In this world of ceaseless market flows, all our most crucial, inescapable, and most human moments are shaped as profit centers. This is so with our birth, our education, our desires, longings, and passions, our fears, our illnesses, our old age and our death. Someone always must pay. Someone always must profit. And yet, and yet, always there is a different voice, a hidden longing, something always on the horizon of the way we usually think and act.

We . . . chafe in the nets of the world

Our deep longings remain unfulfilled. . . .

The endless needs of marketplace and court

Will stain and scrape your jade-white face

What they take is heavier than mountains

What they give is lighter than dust.—Li Bo, trans. Kidder Smith and Mike Zhai in Li Bo Unkempt

This is a song from over a thousand years ago. Li Bo (or Li Bai), called by some the Banished Immortal, knew what he was talking about. He lived in a hierarchical social order that prized literate culture, history, and moral action. His place in it was never secure. At one time he was simply a wanderer, at another time a courtier celebrated by the Tang dynasty emperor Ming Huang (Xuanzong), then an exile; then, when a rebellion turned the whole empire upside down, he was imprisoned, then again he was a wanderer. He found solace in the pathways by the ever-moving dark rivers and through the silent cloudy mountain ranges. He was in love with the wisdom of friends and the worlds of secrets hidden by goddesses in mountains, rivers, alcohol. All these inspired him.

[2]

In a summer class on poetics by Allen Ginsberg at Naropa University, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche spoke about how to write a poem. He said:

“First, let all thoughts go. Let your mind go blank. The ground of the poem is a moment when your mind is empty.

“Whatever arises then begins the poem. From that comes a direction or impulse, a path. How that unfolds is how the poem develops.

“Third is a kind of summing up or an action that brings the impulse to completion and the path to its end. Then the poem is done. The whole process is finished, gone.”

“What if when you let your mind go blank, nothing comes to you?” asked a young man.

“Think of what you love,” said Rinpoche.

This, of course, is not a method for simply constructing poetry. It is a way we can discover poetry as it moves in us beneath the surface, emerges, dwells, dissolves. Inspiration is the yearning that moves at the juncture of ourselves and our worlds. Poetry is the moment when the formless is drawn into the world of form; when the silent enters sound, the invisible enters the visible; when the unmanifest appears manifest, and the unknown is not separate from the known.

Music emerges from our longing intoxicated with sound. Poetry emerges from longing intoxicated with language. An impetuous moment, an urgency, a whisper seeks expression in speech. This impulse is never completely fulfilled, so it presses deeper into reserves of assonance, rhythm. It enters into patterns of images and moves on into forms discovered, imported, or received. Poetry is not a heap of words. A poem holds the elements of speech with close attention, love, precision, tenderness, delirium. It holds the past and present as one. Meanings that cannot be completely defined, oppositions that cannot be resolved, longings that cannot be quite expressed enter the world.

In poetry, language goes beyond language, just as in music, sound goes beyond sound. In music, sound is structured to convey the depths of silence; in poetry, language is arranged to convey truths and intensities beyond words.

Poetry is the moment when the formless is drawn into the world of form, when the invisible enters the visible.

[3]

Following Lao Tzu, alchemists like Li Bo sought to refine the subtle elements of body and mind to produce a perfect expression of harmony, an elixir of immortality, impervious to change and time. Following Confucius, Chinese poets emulated the lyrics in the ancient collection The Book of Songs, which, the sage asserted, would continue to purify language. Poetry does this by extending yearning and meaning beyond the limits of space and time. Intoxicated, spellbound, we return to a kind of communication, both primordial and undying.

In the forthcoming book Li Bo Unkempt, translator Kidder Smith presents the poet as a living principle, a continuing form of inspiration and discovery. Here’s an excerpt from the chapter called “Mystery”—lines from Li Bo’s poem “Drinking alone at North Mountain, sent to Wei Six”:

Now, as I descend this mountain ridge,

all noise subsides, the earth’s at ease.

A range of peaks unfolds across my doorway,

a trickle cuts through rock, pulling down countless springs.

The folding screen of cliffs is lost in clouds,

their caverns unfathomably deep.

At dawn and dusk the river shines its true colors,

the woodland air draws tight with evening chill.

That’s the moment to pick the Red Persimmon

and cultivate the Mysterious Feminine.

I sit with precious texts and the moon, brush the frost off my zither.

In the darkness I pour wine and watch the shadows and empty the cup again.

I miss you, out roaming the world’s dusty wind,

why don’t you ever laugh at yourself?

As Kidder Smith says: “This is a sweet poem. And we could stop right here, were it not for the Mysterious Female.” Citing the French scholar of religion Isabelle Robinet (1932–2000), Smith explains that the Mysterious Female “is a passageway, an entrance situated at the junction of Non-being and Being; it allows Yin and Yang to communicate with each other, and is the place where Yang opens and Yin closes. . . . It is dual, it is singular, it is unmodified. In this logic, we don’t get to transcend duality. Nor even sublate it. We’re stuck with the shebang—there’s no higher or lower view. If you set the yin-yang circle spinning, you can’t tell how many of anything there are. . . .

“Li Bo tells us that he will cultivate the Mysterious Female,” Smith continues. “But Li Bo is doing something more mysterious. He is writing a poem.”

[4]

Our social world of towns, cities, states, countries, our banking and legal systems, our commerce, our communication systems and data banks are integrated globally; no part moves as an entity independent of the whole. Our minds, the way we think, our logic, our assumptions, purposes and habits, all of which we think of as our own, are raw materials, integral to the way this world functions, a part of what it eats, digests, excretes.

What then if our enjoyments of cinnamon buns, coffee, sushi, imported goods, affordable shoes, cars, computers, TV, sports, news, and so on will destroy the worlds of wild fish, of murals on ancient walls, of cranes in flight and gigantic ant colonies, of chestnut trees, bison, old men and women, symphonies, crickets at night, yellow skies, indigo snakes, howler monkeys, dense forests?

Hemmed in on every side, we still have voiceless yearnings. We don’t know exactly what we seek, or how to take steps that would bring us closer.

[5]

Considered to be an equal of Homer, Dante, or Shakespeare (or, we could add, Li Bo), Kalidasa is the most renowned poet in classical Sanskrit. Exactly when he was born and lived no one knows, but legends say that Kalidasa was a cowherd, a simpleton who could barely talk. He was also extraordinarily beautiful. Jealous courtiers tricked the King’s haughty daughter into marrying him, but when she realized how she’d been tricked, she had him sent to a temple dedicated to Kali, the All Devouring, the Great Mother, and Great Destroyer.

This temple was famous for its stone image of the deity. Her many black limbs seemed to writhe like serpents in flickering lamp light; her sharp-toothed smile and bloodshot glare paralyzed many visitors. Kalidasa was undisturbed. As instructed, he swept and washed the floors, removed the old offerings from the shrine, set out fresh offerings, fresh flowers, fruit, meat, blood, and alcohol.

Other attendants sometimes amused themselves by tormenting Kalidasa, the handsome fool. They would track mud on the floor, tip over the liquid offerings, and throw the flowers and food offerings everywhere. Kalidasa never complained. He simply cleaned the floor and replaced the offerings. This went on for many years. One day, a bored attendant thought of a new trick. He took some excrement and put this in one of the statue’s 16 outstretched hands.“Look, look,” he whispered to the long-suffering fool. “Special food. The Goddess wants to reward you. Eat.” And so the beautiful cowherd put the feces in his mouth.

At that instant Kalidasa felt a hot breeze. The Great Destroyer’s breath smelled of rotting corpses and blossoming lotus flowers. The Mother of Time exhaled, and the fool’s mind was filled with the knowledge of everything that had ever happened, everythinåg that was happening, and everything that would ever happen, with all the wisdom that encompassed time and all the words and phrases and sentences needed to express all the world’s wisdom, strife, beauty, fear, and splendor. There was no barrier in his mind or separation from the world. From then on, he was called Kalidasa, Servant of Kali. He served the Dark One without interruption, and rivers of words poured out of him, delighting the minds of men and women, illuminating and inspiring them.

[6]

We sit and watch, as if it were a play.

Time flows through us. The conjunction of moments—physical, emotional, historical—that we have come to call “ourselves” is dissolving and re-forming.

The one who is watching is not the one we know. The one who is watching is also slipping off, like a shimmering bubble, rushing by, dodging the solid-seeming rocks, changing shape with flow, plunging, shattering in the rapids. The watcher is evolving and changing to something unfamiliar, someone new.

Suddenly the urgency to slow such headlong continuing catches us; we get up. A sound on the other side of the wall. We must do something. The light needs to be turned on. A glass of water. Something is needed. We seek escape in the tangible. We get up. For a moment it is not so noticeable that time is moving, moving, moving, taking away our surroundings, taking us somewhere, somewhere we cannot know.

Standing up, inevitably, we take a step.

[7]

Wherever he went, Trungpa Rinpoche carried with him a small statue of Milarepa, the 12th-century Tibetan retreatant-yogi renowned for the austerity of his retreat practice and, perhaps even more, for his many songs about path and realization. Rinpoche’s tiny statue of Milarepa was seated cross-legged, holding his right hand up to his ear.

“He’s holding his hand that way so he can hear the dakinis, right?” asked a clever student. (Dakinis, or sky-goers, are female deities who convey and embody the presence of wisdom in subtle and unexpected ways.)

“He’s listening to himself think.” Rinpoche replied brusquely.

One of Milarepa’s most famous songs is “The Rakshasha Demoness of Lingpa Rock.” It tells of a time when Mila was practicing in a high mountain cave. He heard a crackling in the rock wall. A slit in the rock opened, bright light poured out, and a red man entered the cave riding on a black deer led by a beautiful young girl. The man shoved Milarepa hard and then disappeared. The girl turned into a red dog and seized Milarepa’s left toe in her jaws. Milarepa knew that these were all the display of the mountain demoness, Trak Sinmo. She was, as Trungpa Rinpoche said in his book Milarepa, a manifestation of the energy of chaos and destruction as well as inspiration and creativity. This is the energy that rises to challenge both the outer structures that we take for granted, like day and night, the seasons, and so on, and the inner order that we try to impose on the world as we do with our understanding and our discipline.

Milarepa’s song expressed an inner struggle with inspiration, limitation, and the truth that comes out of that struggle.

Though Mila recognized Trak Sinmo as a projection of his own mindstream, he engaged her in a long discussion. The demoness and Milarepa had both long been inspired to realize the union of complete wakefulness compassion. The songs they sang expressed an inner struggle with inspiration, limitation, and the truth that comes out of that struggle. Their interchange began as a debate but eventually evolved into a kind of duet.

Mila began with a song urging the demoness not to oppose the elements of goodness in the natural world or the strivings of other earnest practitioners.

Here are a few lines:

On the crystal snow mountain, the exalted eastern peak,

Is the enriching presence of the white snow lion….

Blizzards, do not rise up to rival him!

To which Trak Sinmo replied:

As you just said:

“On the eastern snow mountain with the crystal topknot

Is the enriching presence of the white snow lion.”

How could a blizzard rise up to rival him?—The Hundred Thousand Songs of Milarepa, trans. Christopher Stagg

With this song she asserted that such afflictions arise only for those who cling to the reality of a self.

Mila was impressed, but then he sang a song praising worldly phenomena as displays of natural liberation. He accused the demoness of not understanding the meaning of the words she used so skillfully and not seeing the reasons for her own hideous form and malicious existence. He encouraged her to follow the path that would allow the mind of enlightenment to arise in her.

The demoness explained that though she had an eminent teacher (Padmasambhava), she could not overcome her selfish appetites and violent fury. Milarepa then castigated her for her persistent evil. He urged her to open her heart and become his student. In the remainder of the songs, first the demoness and then all her followers and family vowed to follow Milarepa until each and every one had developed complete clarity and compassion. In his concluding song, he sang:

The appearances of spirit forms, clinging to them, having the concepts of them, these three;

When they arise, they arise from the practitioner;

When they dissolve, they dissolve back in the practitioner.

All hindrances are the magical display of mind.

If you can’t recognize the emptiness of your projections

But take your own mind as a ghost, then you, the practitioner, are living an illusion.—trans. Christopher Stagg

Although it is true that this story and its poetic cycle tell us about a practitioner encountering and subduing a kind of violent and chaotic energy that obstructed him, it is also about a practitioner overcoming an obstacle within his own mindstream by accepting and joining with that energy. Neither the practitioner nor the demoness destroys the other one; instead, each finds a way to become part of each other’s continuing. Obstacle and inspiration are revealed to be inseparable. Destruction and creation are each other’s mirror.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.