Between Two Worlds, by Joanne Hershfield and Susan Lloyd, 30 minutes, (512-444-7232), individuals, $39.95; institutions, $89.95.

Japanese Pilgrimage: The Pilgrimage to the Eighty-eight Sacred Places of Shikoku, by Oliver Statler, 30 minutes, University of Hawaii Press (808-9568697) and Hartley Film Foundation (800-937-1819), $30.00.

The Inland Sea, directed by Lucille Carra, 56 minutes, video: Home Vision (800-343-4312), $29.95; videodisk: Voyager (800-446-2001), $49.95.

Dream Window: Reflections on the Japanese Garden, directed by John Junkerman, 57 minutes, Smithsonian Institution (800-262-8600), $29.95.

FOR HUNDREDS of years, pilgrims have undertaken a one thousand-mile journey to eighty-eight sacred places on the Japanese island of Shikoku, following in the footsteps of Kobo Daishi, the ninth-century founder of the Shingon (esoteric) school of Buddhism. Kobo Daishi, revered as a saint and a miracle worker, is thought to walk in spirit with each person who undertakes this traditional pilgrimage. Two American films take us along.

Like many Americans, the makers of Between Two Worlds began their trip expecting to encounter the Japan depicted on elegant scrolls, not cities bustling with business suits and blinking neon signs. The film presents a jarring contrast between modern Japan and the searching journeys of Kobo Daishi and generations of pilgrims: unearthly images of silent pilgrims dissolve gracefully into those of misty landscapes and then quickly cut to machines and urban sprawl. The sight of pilgrims busing through temples on schedules that allow for little more than snapshots elicits regretful first-person commentary from one of the filmmakers. This personal narrative is broken up by interviews with monks, pilgrims, and temple workers who assure us that despite an all-too-common tour-bus approach to pilgrimage, spiritual rewards are still reaped by some. One man explained that he wanted to “enter the next world with a spirit of solitude that is not lonely”; a self-proclaimed Japanese hippie from Osaka says he has traveled for a year looking for himself, and gradually has begun to feel that Kobo Daishi is with him.

The filmmakers’ disparaging attitude toward weekend pilgrims proves a bit troublesome, however. In the beginning, over footage of the film crew unloading equipment, a narrator says they were “impatient to start” because they had only “four weeks to do one thousand miles.” Their hurried pace and tales about the trials of making the film begin to feel inappropriate. In the end we have a film that’s more about temples, filmmaking, and unrealized expectations than about pilgrimage; nevertheless, it remains compelling as a witness—however unwitting—to the difficulty of subduing a frenzied modern pace and goal-oriented natures to take a painstaking, slow journey with no regard for consequences.

Oliver Statler has undertaken the pilgrimage several times himself, has lived on the island of Shikoku, and written an authoritative study about it. His personal understanding of and respect for the eighty-eight sacred temples and the teachings of Kobo Daishi flows out to us in his film Japanese Pilgrimage. He guides us through Kobo Daishi’s life, the legends of his teachings, the history of the temples and the land, and the reason for a pilgrimage. Statler’s unobtrusive, informative narration provides explanations for traditional clothing worn by pilgrims, and many other customs associated with the journey through the plains and into the mountains. Knowing that the pilgrims’ white jackets symbolize their willingness to face death during their search for enlightenment, for example, underscores the seriousness of the undertaking.

The film closely follows a formal documentary format: most visuals relate directly to, and expound upon, Statler’s precise lecture. Occasionally though, we are released from our student chairs into a moment of Kobo Daishi’s teachings accompanied simply by poetic images of pilgrims winding through mountain trails or vistas seemingly unchanged from the time Daishi would have looked out over them.

Between Two Worlds leaves us with a slight first taste of a very complicated and ancient tradition. Japanese Pilgrimage gives us as much knowledge as we can handle without feeling overly full. But both films aim simply to serve as an introduction: as a monk in Between Two Worlds warns, worldly desires can never be overcome by undertaking only a partial pilgrimage.

—michelle houston

TWO FILMs recently released on video paint very different portraits of modern Japanese culture. The Inland Sea, directed by Lucille Carra, is a re-creation of author Donald Ritchie’s personal memoir of travel around Japan’s Inland Sea, a sort of Japanese Aegean. Ritchie, an American authority on Japanese culture and cinema, and a long-term resident of Tokyo, sets out in search of a traditional Japanese culture that he believes is rapidly vanishing from the cities of the main islands. It is within the Inland Sea that he hopes to find the Japanese he describes as “the people they ought to be; the people they once were.”

Those who live on the larger islands, Ritchie says, have become disconnected from their own culture. Modern Japanese culture is seen as becoming little more than a compilation of various Western cultures: a coffee shop stocked with magazines from Europe plays Italian opera; a Buddhist priest talks about being a Frank Sinatra fan.

By contrast, although the people on the smaller islands may be aware of Western culture, their lives seem more deeply rooted in traditions that are uniquely Eastern. A calligrapher explains, “I don’t do this for a living. I do as I please because I have plenty of time up here”; a young fisherman firmly states, “My family’s been cultivating seaweed since my grandpa’s time. I am going to make this my life’s work”; and a group of elders gathers at a shrine for an ancient fire ceremony. They seem much more connected with their environment, their heritage, and their spirit, qualities that Ritchie believes have been lost amid the bustle of the modern cities.

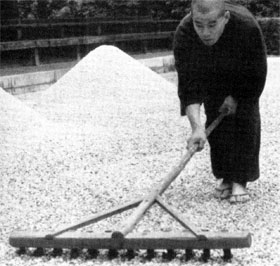

John Junkerman’s Dream Window: Reflections on the Japanese Garden takes a look at Japanese culture from inside the confines of the Japanese garden. Unlike Ritchie, Junkerman finds that ancient traditions still play an integral part in many aspects of Japanese society. Constructed of only the most simple elements—rocks, water, and trees—each Japanese garden is a sacred spot designed for contemplation and identification with nature.

The film is a visually impressive tour of Japan’s most famous gardens, including the Moss Temple of Saiho-ji, Katsura Imperial Villa, Tenryu-ji, and the Ken Domon Museum of Photography. A number of prominent Japanese artists explain the artistic inspiration that they’ve derived from gardens. Toru Takemitsu, who also composed the film’s score (as well as, coincidentally, the score for The Inland Sea), speaks about the garden as an organization of both time and space; Setsu Asakura, one of Japan’s best-known theatrical designers, discusses the minimalist approach to design which is characteristic of the Japanese garden.

The film also takes a look at how ancient philosophies of the garden are still applied in other areas of Japanese culture today. A segment on tea ceremony shows painstakingly precise and purposefully simple movements. This value placed on simplicity is also integral to the art of Japanese flower arrangement. As Hiroshi Teshigahara, head of the Sogetsu school of flower arrangement, explains, “In arranging flowers, you remove everything that is unnecessary in order to strengthen the composition. The less there is the more forceful the work.” Although there is a short segment about the problems facing modern Japanese garden design, and architect Yoshio Taniguchi comments on the application of these traditional philosophies in modern Japanese architecture, the film avoids any discussion of non-Eastern influences on Japanese art or culture today.

The two films have a lot in common. Both take an unhurried pace and are extremely absorbing. Donald Ritchie’s narration throughout The Inland Sea is philosophical and often very personal. Listening to his vivid imagery and poetic style, we suddenly find ourselves beside him taking a long glimpse (through the rich cinematography of Hiro Narita) at a land that seems to be losing its identity. What remains problematic, however, is the film’s unabated nostalgia for an idealized Japan. Shot in thirty-five millimeter and presented on video in dramatic wide-screen format, Dream Window’s graceful snowdrifts, serene rock gardens, and quiet ponds give a powerful sense of each garden’s personality. Still, one becomes a little skeptical that these films suffer from a kind of tunnel vision; they may be looking too closely at what are really just components of a much larger modern Japanese culture—a fluid and adept Japan that builds our cars and stereos and finances our deficit. Perhaps we should bear in mind the words of the Abbot of Shinju-an who says (in Dream Window), “We don’t divide things simply into good and bad, right and left. There is a vagueness, a sense of mu, or space between things. That’s how the universe itself is constructed.”

-Isaac Friedman

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.