The advent of Buddhists who are concerned about world peace, human rights, the environment, and other sociopolitical issues is a development that challenges some common assumptions. Isn’t Buddhism an inwardly focused religion that gives precedence to meditation over any kind of social activity? Isn’t it contradictory to speak of a “socially engaged Buddhism?” While the heart of the tradition may indeed be a solitary spiritual quest, Buddhism also displays remarkable diversity, and there is increasing recognition of the ways in which Buddhists and their institutions become involved in the world. Understandably, Buddhism often appears to promote personal transformation at the expense of social concern. Some Buddhist teachings claim that the mind does not just affect the world, it actually creates and sustains it. According to this view, cosmic harmony is most effectively preserved through an individual’s spiritual practice. Yet other Buddhists amend the notion that mind is the primary or exclusive source of peace, contending that inner serenity is fostered or impeded by external conditions. Buddhists who place importance upon social factors and social action believe that internal transformation cannot, by itself, quell the world’s turbulence.

In China, countless generations of Confucianists accused Buddhists of withdrawing from the world out of selfishness. Wang Yang-ming (1472-1529) charged that Buddhists were “afraid of the troubles involved in the relationships between father and son, ruler and subject, and husband and wife; therefore [they] escape from these relationships.” In Japan, Buddhism is faulted for becoming too subservient to the state. D. T. Suzuki, ordinarily a defender of Zen, did not exalt its role in the sociopolitical realm: “[Zen] may be found wedded to anarchism or fascism, communism or democracy…or any political or economic dogmatism.” Most Western scholars have also tended to perceive Buddhism as world-denying, passive, or socially inept. Max Weber was one of the first to declare that Buddhist devotees carry the “asocial character of genuine mysticism…to its maximum.”

Yet there are other specialists who have begun to question such interpretations. Instead they perceive in Buddhism a creative tension between withdrawal and involvement, an underlying synonymity between work on oneself and work on behalf of others. Evidence supporting this viewpoint is found in doctrine, in practice, in legend, and in history. Thus the preeminent virtues in Theravada Buddhism are self-restraint and generosity; in Mahayana Buddhism, the highest goals are wisdom and compassion. According to Tibetan scholar Robert Thurman, certain Mahayana texts reveal the outlines of a society that is “individualist, transcendentalist, pacifist, universalist, and socialist.” Carried to an extreme, such interpretations envision an ideal Buddhism too far removed from its actual historical development. But the thrust of the argument is constructive: to show that the Buddhist tradition contains untapped resources for skillful social action and peacemaking, accessible to Buddhists and non-Buddhists alike.

It is noteworthy, in this regard, that the story of the Buddha’s spiritual journey climaxes with his enlightenment but does not end there. Even as he was savoring the blissful state that followed his awakening, he was approached (in the traditional account) by a delegation of gods, who begged him to give up his private ecstasy so he could share his awakening with those who still suffered. This encounter and its outcome, however legendary, make the point that spiritual maturity includes the ability to actualize transcendent insight in daily life. The Buddha is said to have wandered across northern India for forty years, tirelessly teaching the dharma. His decision to arise from his seat under the Bo tree and go out into the world can be considered the first step of a socially engaged Buddhism. The Buddha’s discourses, which had revolutionary force in the society of his time, include countless passages dealing with “this-worldly” topics such as politics, good government, poverty, crime, war, peace, and ecology.

Is it possible to become involved without becoming attached? Must one be partially or fully enlightened before one can act in the world with true wisdom and compassion?

A socially engaged Buddhism raises compelling questions. For instance, is it necessary to prove that engagement was an integral feature of original Buddhism, or is it enough to demonstrate that it can be derived naturally from Buddhism’s past? What are the differences between Buddhist-inspired activism and activism that arises from other religious or secular belief systems? A number of challenging practical issues also emerge: Is it possible to become involved without becoming attached? Must one be partially or fully enlightened before one can act in the world with true wisdom and compassion? Such topics are of particular concern to Buddhism’s new adherents in the West.

The central Buddhist tenet of nonviolence is freely interpreted and applied by contemporary Buddhist activists, in part because traditional sources cannot provide case-by-case guidelines for behavior. Are there situations in which a violent response would be justified? Though certain scriptural passages contend that a Buddhist “must not hate any being and cannot kill a living creature even in thought,” one influential sutra states that in order to protect the truth of Buddhism it may be necessary to bear arms and ignore the moral code. Certain schools refrain from addressing such issues theoretically; instead they claim that people who have trained themselves to live each day consciously and nonviolently will intuitively know how to react in a given situation. One commendable response to an imminent attack is illustrated in a Zen anecdote:

When a rebel army swept into a town in Korea, all the monks of the Zen temple fled except for the abbot. The general came into the temple and was annoyed that the abbot did not receive him with respect. “Don’t you know,” he shouted, “that you are looking at a man who can run you through without blinking?” “And you,” replied the abbot strongly, “are looking at a man who can be run through without blinking!” The general stared at him, then made a bow and retired.

A feature that originally set Buddhism apart from Hinduism, and that still characterizes it in several cultures, is an expressed opposition to the slaughter of animals. Rather than making a sharp distinction between humans and animals, Buddhism groups them together as “sentient beings,” subject equally to birth and death, pain and fear. According to the doctrine of karma, people can be reborn as animals, and animals can be reborn as people, so one’s past or future relatives may turn up in the most unlikely places. Hence the adoption of vegetarianism by certain Buddhists. Asian Buddhists ceremonially liberate animals in captivity, buying them from breeders or pet stores and releasing them back to their natural habitats. In the West, this sensibility is expressed through support for animal rights and biodiversity. In fact, “ecoBuddhism”—the convergence of certain aspects of Buddhism and environmentalism—may provide a powerful new vehicle for Buddhist involvement in the world.

Nonviolence belongs to a continuum from the personal to the global, and from the global to the personal. One of the most significant Buddhist interpretations of nonviolence concerns the application of this ideal to daily life. Nonviolence is not some exalted regimen that can be practiced only by a monk or a master; it also pertains to the way one interacts with a child, vacuums a carpet, or waits in line. Besides the more obvious forms of violence, whenever we separate ourselves from a given situation (for example, through inattentiveness, negative judgments, or impatience), we “kill” something valuable. However subtle it may be, such violence actually leaves victims in its wake: people, things, one’s own composure, the moment itself. According to the Buddhist reckoning, these small-scale incidences of violence accumulate relentlessly, are multiplied on a social level, and become a source of the large-scale violence that can sweep down upon us so suddenly. In contrast, any act performed with full awareness, any gesture that fosters happiness in another person, is credited as an expression of nonviolence. One need not wait until war is declared and bullets are flying to work for peace, Buddhism teaches. A more constant and equally urgent battle must be waged each day against the forces of one’s own anger, carelessness, and self-absorption.

One of the features that distinguishes this emerging network as “Buddhist,” especially for the Westerners who are involved, is the conviction that social work entails inner work, that social change and inner change are inseparable.

Though precedents for a politically responsive Buddhism can be found throughout the Buddhist tradition, a new phase of Buddhist activism has emerged in the past thirty years. The participants in this nascent movement come from many nations, from diverse branches of Buddhism, and from different walks of life. They are monks, nuns, and laypeople, Asians, Americans, and Europeans, adherents of Mahayana, Theravada, and Vajrayana Buddhism, scholars and spiritual masters, First World homemakers and Third World insurgents. Individual agendas vary, but the ideal (at least for those who articulate ideals) is to transform oneself while transforming the world.

One of the features that distinguishes this emerging network as “Buddhist,” especially for the Westerners who are involved, is the conviction that social work entails inner work, that social change and inner change are inseparable. While other religiously motivated activists share this outlook to some degree, it seems to be applied most consistently by engaged Buddhists. A reform movement that is pursued only from a sociopolitical standpoint, they assert, will at best provide temporary solutions, and at worst it will perpetuate the very ills it aims to cure. Effective social action must also address the greed, anger, and ignorance that cripple us as groups and as individuals. Work on oneself is therefore essential, though it means different things to different Buddhists.

Another principal concept that underlies most forms of engaged Buddhism is the interdependence of all existence (and nonexistence). The paper on which these words appear is the product of countless causal factors—tree, rain, cloud, logger, trucker, those who perfected the papermaking process, the fuels used to manufacture and transport the product, the sources of those fuels, and so on, endlessly. Just as a stone tossed into a still pond creates wavelets in any direction, every act—indeed every thought—is believed to have infinite repercussions in realms seen and unseen. A few drinks too many by the captain of an oil tanker may cause it to run aground, spoil many miles of coastline, ruin some local businesses but make others prosper, affect gasoline prices nationwide, create new jobs for lawyers and congressional staffers, and so on, endlessly. Buddhist terms such as nonduality, interrelatedness, or interbeing all point to this idea. If each person is not fundamentally separate from other beings, it follows that the suffering of others is also one’s own suffering, that the violence of others is also one’s own violence.

Among the figures who have enhanced the prospects of a newly engaged Buddhism, the Vietnamese Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh is one of the most influential. (Thich is the surname taken by all Vietnamese monks, and Nhat Hanh means “one action.” The pronunciation is tick-not-hahn.) Born in 1926, Nhat Hanh entered a monastery at the age of sixteen. In the 1950s he opened the first Buddhist high school in Vietnam and helped found Van Hanh Buddhist University in Saigon. A prolific writer since his youth, he has published essays, stories, and poems in Vietnamese, French, and English. His 1963 book Engaged Buddhism marked the first use of that term. During the Vietnam War, Nhat Hanh led a nonpartisan Buddhist movement that sought a peaceful end to the conflict. His activities were opposed by Saigon and Hanoi alike, and thousands of his companions were shot or imprisoned as they struggled amidst the fighting to rebuild villages and resettle refugees.

In 1966, Nhat Hanh accepted a series of speaking engagements in the United States and Europe, where he provided a rare firsthand account of the torments and aspirations of the Vietnamese. He met Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, Pope Paul VI, members of Congress, U.N. officials, and Thomas Merton, who concluded: “He and I see things in exactly the same way.” Nhat Hanh then learned that he would not be allowed to return to Vietnam. He received asylum in France and became chairman of the Buddhist delegation to the Paris peace talks. Still in exile, he now resides in Plum Village, France, meditating, gardening, writing, leading retreats, and coordinating international relief efforts for refugees and children. Nhat Hanh’s calm and deeply penetrating manner prompted an American Zen teacher to call him “a cross between a cloud, a snail, and a piece of heavy machinery—a true religious presence.”

For Thich Nhat Hanh, engaged Buddhism encompasses meditation, mindfulness in daily life, involvement in one’s family, and political responsiveness. At times, he even dismisses the term he coined as a misnomer: “Engaged Buddhism is just Buddhism. If you practice Buddhism in your family, in society, it is engaged Buddhism.” What is close at hand cannot be neglected:

We talk about social service, service to humanity, service for others who are far away, helping to bring peace to the world—but we often forget that it is the very people around us that we must live for first of all. If you cannot serve your wife or husband or child or parent, how are you going to serve society?

Westerners attracted to Buddhism have been looking for ways to actualize its tenets in a culture that lacks a strong commitment to monasticism. Nhat Hanh presents a style of teaching and practice that might be described as spiritually democratic: students are urged to practice as best they can on their own; they are not asked to make a personal commitment to a master; and they are welcome to maintain prior affiliations with other religious groups (including Buddhist ones). Nhat Hanh’s vision of a family-oriented practice may yield a new synthesis of Buddhist spirituality and actual social conditions. Or it may be unrealistic, especially in a non-Buddhist culture, to expect families to provide much of the support and guidance that larger religious communities have traditionally offered.

At the heart of Nhat Hanh’s teachings is a conviction that peacework is more of an inner activity than an outer one: “It is not by going out for a demonstration against nuclear missiles that we can bring about peace. It is with our capacity of smiling, breathing, and being peace that we can make peace.” Nhat Hanh further claims that personal peace is immediately accessible if one knows where to look; he tells readers and listeners to “touch” the peace and joy that is already within them. First, some common mental habits must be recognized and stopped:

It is ridiculous to say, “Wait until I finish this, then I will be free to live in peace.” What is “this”? A diploma, a job, a house, the payment of a debt? If you think that way, peace may never come. There is always another “this” that will follow the present one. If you are not living in peace at this moment, you will never be able to.

Several of Nhat Hanh’s books about meditation include little or no reference to political peacework or other forms of social engagement. When he considers meditation broadly, he writes that it is not an escape from suffering or a withdrawal from society. On the contrary, meditation prepares one for “reentry into society” and helps one to “stay in society.” Like many Buddhists, Nhat Hanh values the breath as an indispensable tool for calming the body, focusing the mind, and clarifying awareness. “Breathing is a means of awakening and maintaining full attention in order to…see the nature of all things,” he asserts. The method he prefers is focused awareness: “Breathing in, I am aware that I am breathing in. Breathing out, I am aware that I am breathing out.” Because modern people rarely live in monasteries or forest retreats, Nhat Hanh urges them to maintain awareness of the breath throughout their daily activities.

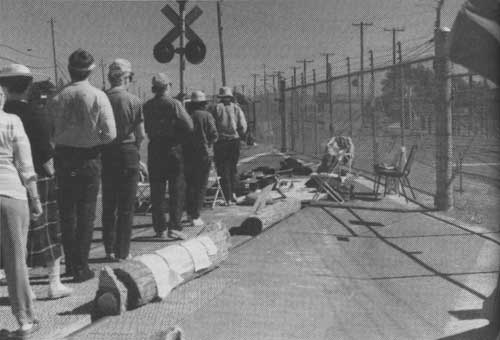

Like other contemporary Buddhist activists, Nhat Hanh elicits critical responses from certain quarters. Buddhist practitioners who give precedence to prolonged meditation suspect that Nhat Hanh overemphasizes mindfulness at the expense of deep self-realization. In contrast, those who give priority to the resolution of urgent social problems tend to regard Nhat Hanh’s teachings as too contemplative or simplistic. How many people, they ask, will be persuaded that breathing or smiling has a significant impact on the world? Are hungry refugees expected to enjoy inner peace regardless of their external circumstances? Nhat Hanh may also invite criticism as a political strategist. He readily acknowledges the failures of his peace movement in Vietnam, though he points out that his “lonely” band of volunteers was pitted against the two most powerful nations in the world. “I suffered a lot from the war,” he once confided. “When five of my workers were assassinated by the bank of a river, someone told me I was the commander of a nonviolent army and I had to be prepared to take losses. But how could I not cry?” Looking back, Nhat Hanh concludes that the odds against success were overwhelming: “I see that the nonviolent struggle for peace in Vietnam was a beautiful one. It did not succeed very much, not because it was wrong, but because it did not have all the conditions it needed.”

In 1977, Nhat Hanh was thwarted in a well-intentioned attempt to rescue hundreds of boat people in the Gulf of Siam. His plan was to ship them secretly to Guam or Australia, but an untimely leak to the press alerted local governments, and the boat people were instead consigned to refugee camps in Malaysia. In response to this setback, Nhat Hanh went into partial retreat for five years.

Whatever its practical or theoretical limitations, Nhat Hanh’s model of engaged Buddhism seeks to achieve a constructive balance between inner work and concern for others. In his vision, spiritual practice and political activism are mutually reinforcing, not mutually exclusive. Even in the face of the terrible violence he has encountered, Nhat Hanh continues to believe that inner peace is possible amidst the most hellish conditions. Alluding to the boat people, he asserts that in an overcrowded boat adrift on a turbulent sea, if there is just one person who remains inwardly calm, everyone benefits immeasurably.

There have been turning points in Buddhism’s past history when people believed that they lived in an age of religious degeneration and potential worldwide disaster. Often during such periods the usual sources of religious inspiration were no longer persuasive, and the chances of personal salvation seemed slim. And yet these were also some of the most creative eras in Buddhism’s development. Today, many Buddhists are once again struggling to reestablish meaningful foundations for the spiritual striving of individuals and the harmonious functioning of society. An important new element in the mix is international and planetary awareness. Whereas Buddhism was once identified only with particular cultures, the modern world allows for a shared understanding of Buddhism that bridges cultural variations without denying them. Some form of social engagement will undoubtedly be an accepted component of a globally oriented Buddhism, though the expressions of that engagement will continue to vary.

The Heart of Practice

Thich Nhat Hanh

The following excerpt is from Thich Nhat Hanh’s Being Peace, and is reprinted with permission from Parallax Press.

Meditation is not to get out of society, to escape from society, but to prepare for a re-entry into society. We call this “engaged Buddhism.” When we go to a meditation center, we may have the impression that we leave everything behind—family, society, and all the complications involved in them—and come as an individual in order to practice and search for peace. This is already an illusion, because in Buddhism there is no such thing as an individual.

Just as a piece of paper is the fruit, the combination of many elements that can be called non-paper elements, the individual is made of non-individual elements. If you are a poet, you will see clearly that there is a cloud floating in this sheet of paper. Without a cloud there will be no water; without water, the trees cannot grow; and without trees, you cannot make paper. So the cloud is in here. The existence of this page is dependent on the existence of a cloud. Paper and cloud are so close. Let us think of other things, like sunshine. Sunshine is very important because the forest cannot grow without sunshine, and we humans cannot grow without sunshine. So the logger needs sunshine in order to cut the tree, and the tree needs sunshine in order to be a tree. Therefore, you can see sunshine in this sheet of paper. And if you look more deeply, with the eyes of a bodhisattva, with the eyes of those who are awake, you see not only the cloud and the sunshine in it, but that everything is here: the wheat that became the bread for the logger to eat, the logger’s father—everything is in this sheet of paper.

The Avatamsaka Sutra tells us that you cannot point to one thing that does not have a relationship with this sheet of paper. So we say, “A sheet of paper is made of non-paper elements.” A cloud is a nonpaper element. The forest is a non-paper element. Sunshine is a non-paper element. The paper is made of all the non-paper elements to the extent that if we return the non-paper elements to their sources, the cloud to the sky, the sunshine to the sun, the logger to his father, the paper is empty. Empty of what? Empty of separate self. It has been made by all the non-self elements, non-paper elements, and if all these non-paper elements are taken out, it is truly empty, empty of an independent self. Empty, in this sense, means that the paper is full of everything, the entire cosmos. The presence of this tiny sheet of paper proves the presence of the whole cosmos.

In the same way, the individual is made of nonindividual elements. How do you expect to leave everything behind when you enter a meditation center? The kind of suffering that you carry in your heart, that is society itself. You bring that with you, you bring society with you. You bring all of us with you. When you meditate, it is not just for yourself, you do it for the whole society. You seek solutions to your problems not only for yourself, but for all of us.

Leaves are usually looked upon as the children of the tree. Yes, they are children of the tree, born from the tree, but they are also mothers of the tree. The leaves combine raw sap, water, and minerals, with sunshine and gas, and convert it into a variegated sap that can nourish the tree. In this way, the leaves become the mother of the tree. We are all children of society, but we are also mothers. We have to nourish society. If we are uprooted from society, we cannot transform it into a more livable place for us and for our children. The leaves are linked to the tree by a stem. The stem is very important.

I have been gardening in our community for many years, and I know that sometimes it is difficult to transplant cuttings. Some plants do not transplant easily, so we use a kind of vegetable hormone to help them be rooted in the soil more easily. I wonder whether there is a kind of powder, something that may be found in meditation practice that can help people who are uprooted be rooted again in society. Meditation is not an escape from society. Meditation is to equip oneself with the capacity to reintegrate into society, in order for the leaf to nourish the tree.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.