Twenty hours in the air and half a planet away from home, we finally catch sight of Mongolia’s capital, Ulaanbaatar, in a treeless valley surrounded by the four sacred peaks of Bogd Khan, Bayanzurkh, Chingeltei, and Songino Khairkhan. It’s 10 p.m. when we land, yet the sun is only just setting at this northern latitude. Burnt-orange light streaks the ground between long shadows. The darkening sky and the treeless plain squeeze between them the last minutes of day. On the horizon, an iridescent thunderstorm pours torrential rain down its mushroom stalk. Soviet-era helicopters sit in the weeds and rust under sagging rotors.

My brother Grant and I have come to this historically Buddhist land to see the state of the dharma thirteen years after the end of Soviet rule. For centuries, the country has had strong ties to Tibetan Buddhism—indeed, before the Soviet repression began in 1921, some estimates counted more than 98 percent of the population as Buddhist, though recent studies suggest that that percentage has dropped significantly.

At the airport’s baggage claim, we see why: A battalion of well-groomed Mormon missionaries awaits us, wearing black suits and gold name tags. They are cheery, polite, relentless. We soon learn that they are the dharma’s main competition for the hearts and minds of Mongolians. More troops to the front lines.

Before heading into the country, we spend two days in Ulaanbaatar itself. Almost half the country’s population crowds into this capital city of one million. Deep potholes and broken streetlights reveal the surface state of a crumbling infrastructure. On the broad avenues, urban culture and ancient style clash. Young girls queue up for water at public pumps. One-horse wagons dodge buses and cars, which careen wildly in no-rules driving. Young toughs in L.A. Dodgers caps play pool on tables sitting out in the open. Exhaust fumes, dust, and cooking smoke hang in the air. Animal bones litter the ground, some with remnants of flesh and fur still clinging to them. Throughout, dirt streets meander, bordered by ramshackle fences that shield family gers, the traditional round tents of the Mongols, from random theft.

During their rule, the Russians imposed a command economy on this nomadic people. When they left, the economy sputtered to a halt. The Russians had also destroyed 700 monasteries, forced thousands into slave labor, and slaughtered 17,000 monks and 10,000 citizens, many of whom lie buried in mass graves, with bullet holes in the backs of their heads. The surviving monks were forced to abandon Buddhism, marry, and enter secular life. Even so, many continued to practice in secret and kept sacred objects hidden for a time when the dharma could reemerge.

That time came in 1991, when a peaceful revolution led to a democratic government. The Mongolian dharma emerged from seven decades of subjugation severely weakened. Christian missionaries, particularly Mormons, have swarmed into the spiritual vacuum seeking converts, while the consumer din of Mongolia’s emerging Western-style market economy threatens to drown out the quiet clarity of the dharma.

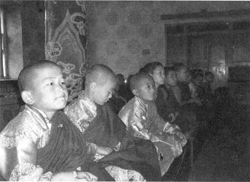

But the dharma is adapting. Prime Minister Nambaryn Enkhbayar is a practicing Buddhist (and, yes, a Communist in a democratic republic) who is keenly interested in preserving Mongolia’s Buddhist heritage. Many provincial governors and members of parliament share his passion. We visited Gandan Monastery in Ulaanbaatar, Erdene Zuu and Shankh Khiid Monasteries in the ancient capital Kharkhorin, and a temple in Dalanzadgad, and talked to abbots, lamas, and monks. Speaking to us in their rhythmic, whispering language of soft glottal inflections, they showed us where they had restored to their spiritual place the relics and statuary their predecessors had hidden during the Soviet era.

Out in the country, the endless blue sky and undulating hills exude a primeval magic that is almost unbearably moving. The jeep ride is unbearably moving, too—as in teeth-chattering, organ-jarring, head-banging bumpy. Mongolian “roads,” well, aren’t.

In Kharkhorin we drink airag, fermented mare’s milk that tastes like salty cream and tonic water. Nice buzz. From Dalanzadgad, we drive through the minimalist majesty of the Gobi, dodging sand devils and camel carcasses while skimming over the trackless plain. A white vulture soars above us in a Yol Valley canyon. The Flaming Cliffs lick the horizon at sunset. And later that night, under glimmering starlight at Three Camels Lodge, two traditional singers, Nara and Eata, sing a praise to Altai Mountain. All the while, we eat dried mutton, and mutton patties, and boiled mutton, and mutton meat sauce, and mutton soup, and never wonder why we don’t see any sheep: We’ve undoubtedly eaten them all.

Certainly, the Bible-toting missionaries and the clangorous Western marketers may tout their wares, but the Mongolian dharma, frail as it may appear now, seems poised to transcend this moment in history. I see it comfort an old woman turning a prayer wheel, and see it sustain the monks rebuilding their cherished sites. I feel it riding the Gobi wind and steeped in the rock strata of these old mountains.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.