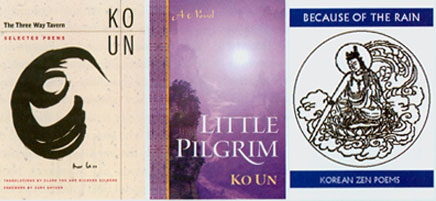

THE THREE WAY TAVERN: SELECTED POEMS

Ko Un; Clare You and Richard Silberg, Translators

Berkeley: University of California Press, April 2006

184 pp.; $45.00 (cloth), $16.95 (paper)

BECAUSE OF THE RAIN: KOREAN ZEN POEMS

Won-Chung Kim and Christopher Merrill, Translators

Buffalo: White Pine Press, April 2006

96 pp.; $14.00 (paper)

LITTLE PILGRIM: A NOVEL

Ko Un; Brother Anthony of Taize and Young-Moo Kim, Translators

Berkeley: Parallax Press, 2005

381 pp.; $18.95 (paper)

THE GREAT POET KO UN, born in Kunsan, Korea, in 1933, grew up under the harsh Japanese occupation of his country that ended only after World War II. As a witness to the countless everyday horrors of occupation followed by the fratricidal slaughter of the Korean War, Ko Un was concerned from an early age with the reality of suffering. He spent his early years of adulthood as a monk in the Korean Son (Zen) tradition, and published his first volume of poetry in 1960 while still living in the renowned Haeinsa Temple. He left the sangha three years later and lived variously as a school teacher, drunk, and political activist who protested the oppressive South Korean dictatorship. He was jailed several times, tortured, locked away in prolonged solitary confinement, and finally pardoned as democracy began to emerge in South Korea. He married for the first time in 1983, a year after his release, and became a true householder and family man, at the age of fifty.

Throughout these many lives, Ko Un continued to write a torrent of poetry, which has been trickling out in English translation over the last decade or so. The Three Way Tavern brings together some of Ko Un’s more recent work, taken from several collections published in the 1990s. Although these poems cover a wide range of subjects, the influence of Ko Un’s early Zen training is still evident three decades after his disrobing, particularly in the haiku-like “Son poems” that are included in this collection. Consider this tiny gem, titled “Friend”:

With the dirt you dug,

I made a Buddha.

It rained,

and Buddha turned to mud.

Now what good’s the clear sky?

And this heretical tribute, “Way”:

This way to Nirvana

Nonsense.I’ll go my way

over the rocks, through the waters,

that’s the dead way of my master.

The Three Way Tavern also includes twenty-three selections from Ten Thousand Lives, Ko Un’s monumental project, conceived in prison and still ongoing today, to capture the essence of ten thousand ordinary people in verse. The examples here concern beggars, street urchins, an aging aunt, and a disappointed father, as well as two moving stories from Ko Un’s own peasant childhood. These are fuller works, lingering on each character long enough to tell an often tragic story. The “comfort woman” Mansooni is introduced in this way:

Though her face was full of freckles

like spilled sesame seeds,

her pretty eyes and eyebrows

swept up in a breeze;

her shadow cast on the water

was an absolute beauty.

Mansooni is taken one day to the Japanese military’s so-called comfort unit “wearing her rising sun bandana,” and when the war ended:

Liberation came, everyone returned,

white bellflowers bloomed and

cicadas sang,

but there was no word of Mansooni.

The sad politics of Korea, wedged between the great powers of China and Japan, has shaped Ko Un’s life from the beginning, and many of these poems—like “Mansooni, Comfort Woman”—are essentially political. As a result of his personal history as well as the significance of his subjects, Ko Un, who has been nominated twice for the Nobel Prize in literature, is widely regarded as South Korea’s national poet today. Inevitably, there are some references in the poems to Korean culture and geography that will be lost on most in the West, but these are few. In these finely rendered translations by Clare You and Richard Silberg, the vast majority of the poems in this collection achieve a universality that will touch readers from any background.

For those who wish to delve more deeply into the long tradition of Zen poetry of Korea, White Pine Press has released Because of the Rain, the latest installment of their beautiful “Companions for the Journey” series. The collection spans over a thousand years, offering what co-translator Christopher Merrill accurately describes as “a distillation of Zen doctrine and practice, glimpsed through a Korean lens.” A helpful counterpoint to Ko Un’s modern work, these are wonderfully pure nuggets of Zen insight; see, for example, the title poem, written by Jinkag Haesim in the twelfth or thirteenth century:

How I love the natural Buddha

who waters the wide world with his

mercy.

No place to hide in the vast sky;

even inside the overturned bowl it’s

wet.

WHILE KO UN WAS STILL a monk in training, his master instructed him to read the Avatamsaka or Flower Ornament Sutra. Although uninterested at first, Ko Un returned to the scripture later in life and began writing a retelling of the sutra’s long final chapter that was published serially in a Korean newspaper starting in 1969. Twenty-two years later, his project was at last completed, and the collected series became a best-selling book in Korea and was even made into a movie. Echoing the original sutra, Ko Un’s account traces the journey of the young orphan Sudhana through India at the time of the Buddha and describes his encounters with fifty-three teachers along the way.

Today this fictionalized sutra appears in its first English translation under the title Little Pilgrim: A Novel. The subtitle is perhaps a little misleading: although it is fiction, it does not form a coherent fictional narrative in the contemporary sense. But there is much interesting material here, and the underlying philosophy of interconnectedness resonates throughout, as in the early lesson from Meshashri, a cave-dwelling monk, who explains: “Everything in this world is sacred. . . . All things are truth and teachers of truth.” Later, a local doctor speaks to Sudhana and elaborates:

Bodhisattva awakening means releasing all beings from their sufferings, becoming a fire to burn away avarice and self-love, becoming a cloud bringing rain, becoming a bridge so that all sentient beings and all living creatures can cross the river of life and death. Behold. I enter the sea that contains all these properties of bodhisattva awakening and lay down my name within the sea. I lay down all my words within the sea. What became of the diseases I have cured, once they have left the bodies they were tormenting? Where did they go? Behold. I lay down all diseases in the sea, too.

While Sudhana’s many lessons are captivating, the prose feels wooden at times, and readers can become somewhat lost in the ceaseless travels. Books like this are long out of fashion in the West; the broadly similar work The Pilgrim Kamanita by Danish-German author Karl Gjellerup was a bestselling novel in America and Europe, but that was published a century ago. In the end, Ko Un’s poetry is the more accessible side of his work, drawing us into the deep wisdom he’s collected through practice, writing, and life. The Three Way Tavern is a rich and varied introduction to a great poet at the height of his craft.

In “Afterlife,” one of the last poems in the collection, Ko Un proclaims “I won’t be born as a human being ever again,” and he modestly suggests that he may end up an amoeba in his next life. Judging from the insight, determination, dignity, and compassion displayed in this work, that seems unlikely.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.