It seems that everyone wants change: the latest tech gadget, a different job, a better relationship. Things “as they are” are somehow just not quite satisfying. Buddhists will recognize this situation as evidence of the first noble truth: dukkha (suffering or inherent “unsatisfactoriness”) is simply part of existence.

We often assume that happiness can be achieved by changing something in our external environment. But this assumption overlooks the fact that much of our suffering is perpetuated by our own minds. Our mental patterns can shape the way we respond emotionally to others, the way we perceive events, and whether we view the world and others as basically good or inherently flawed. They also affect simple, everyday aspects of our lives. Mental and behavioral habits underlie the vast majority of our experience, and most operate without our awareness. Under the influence of such patterns, we can end up living on autopilot.

In Buddhism, these tendencies of mind are central to the idea of karma, according to which each moment of consciousness is conditioned by previous moments, and the sum of our previous experience is the cause of each subsequent moment of experience. Our actions (including thoughts as well as observable behavior) leave a trace in our minds, making it more likely that similar actions will occur in the future. The Korean Zen teacher Daehaeng Kun Sunim summarized it well: “People are often careless about the thoughts they give rise to, assuming that once they forget about a thought, that thought is finished. This is not true. Once you give rise to a thought, it keeps functioning, and eventually its consequences return to you.”

These ancient ideas about karma—at least as they relate to a single lifetime—are mirrored with surprising detail in the foundations of modern neuroscience. One of the most fundamental principles of neuroscience is known as Hebb’s law, also called cell assembly theory. In his 1949 book, The Organization of Behavior, the Canadian psychologist Donald Hebb laid out a principle that is often summarized by the phrase “Neurons that fire together, wire together.” In his seminal work, Hebb proposed that “any two cells or systems of cells that are repeatedly active at the same time will tend to become ‘associated,’ so that activity in one facilitates activity in the other.” This is the basic premise of neural plasticity—the ability of the brain to change through experience.

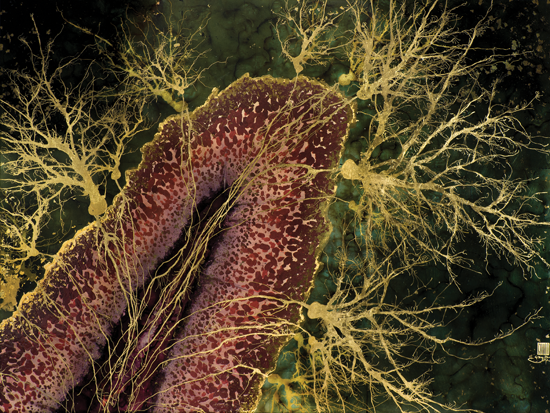

The mechanisms of neural plasticity are being revealed through an ever-increasing and nuanced body of research, showing how our brain networks are physically created and updated on a micro-level. Imagine two neurons connected such that activity in the first neuron makes the second more likely to fire. If we repeatedly stimulate the two neurons simultaneously, after a few hours, the same initial stimulation of the first neuron will lead to a larger electrical response in the second neuron—a change due in part to the release of more chemical neurotransmitters from the first cell and the presence of a greater number of receptors for that neurotransmitter on the second cell. These molecular changes serve to facilitate the relationship between the two neurons so that they are more strongly coupled. If repeated co-activation takes place over a longer time, the neurons will physically change their shape, sprouting new connections to solidify this effect even more.

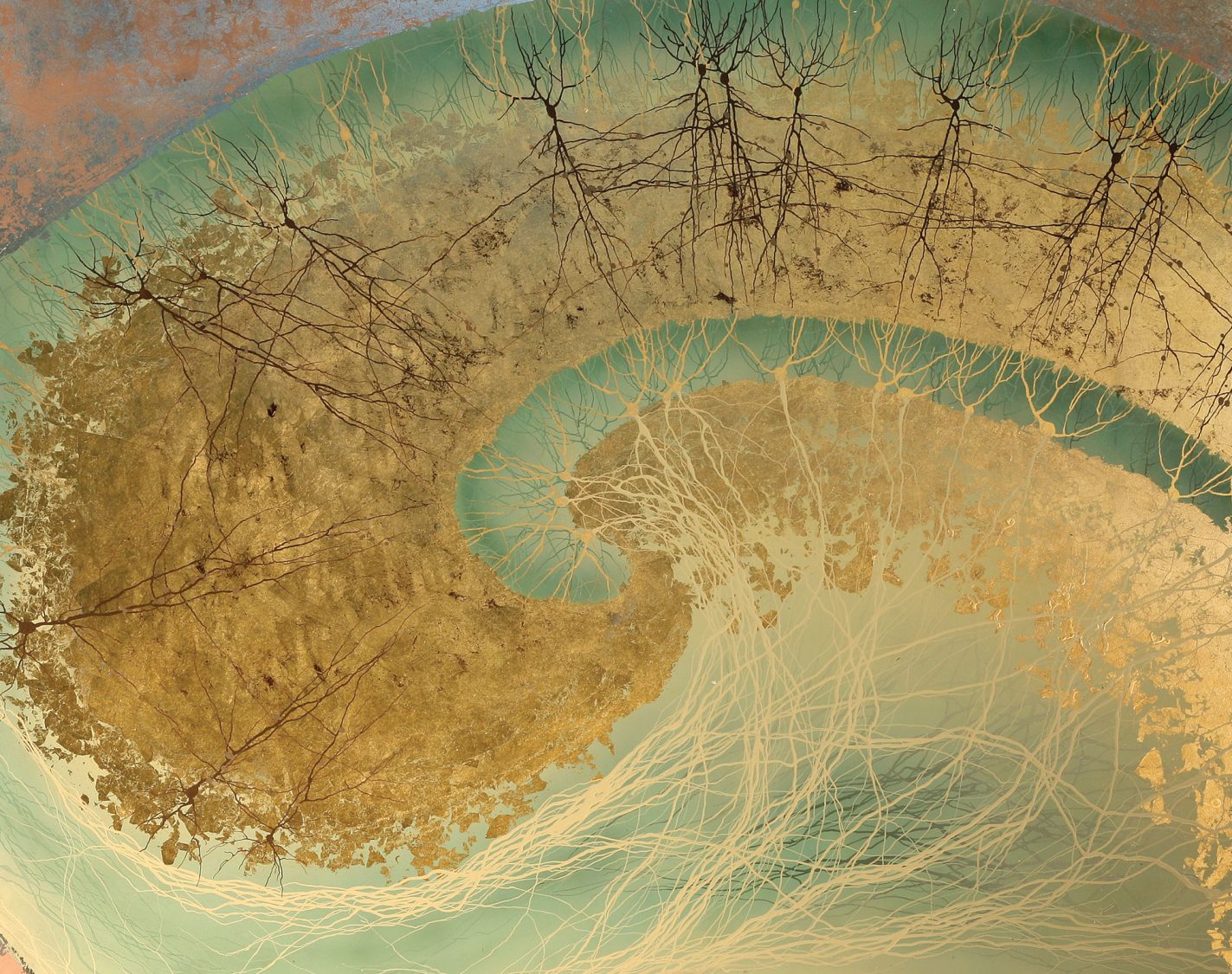

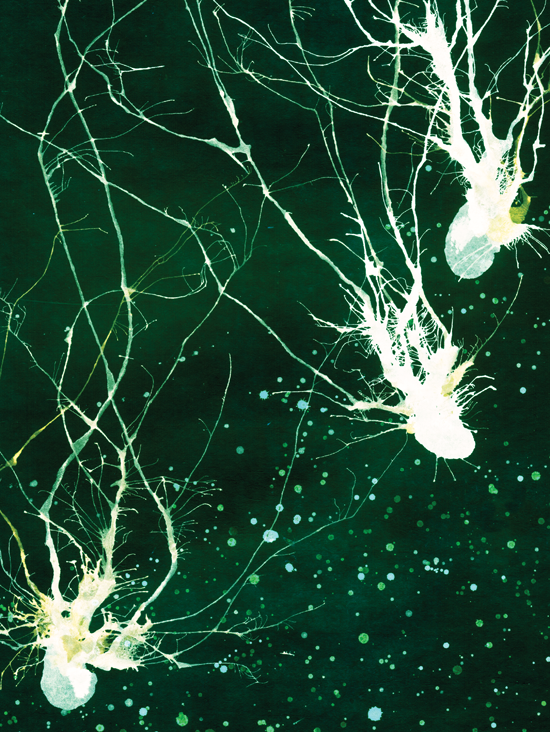

The description above is a simple example of an interaction between two cells, but of course in the living brain, it is a process taking place at millions of connections every second. And each neuron is in conversation with thousands of others, creating an almost impossibly elaborate web of activity. Through the continual process of neural association, we slowly build up strong networks related to the things we experience frequently. These neural networks reflect our personal knowledge about a given object, person, or situation—in the form of sense perceptions, memories, emotions, thoughts, and behavioral responses.

Millions of neurons come alive in a complicated network of activity that underlies each experience.

As we move through our lives, brain circuits that are used more frequently become “hardwired”; that is, they are easier to activate than new or unused connections. Because less energy is needed for these familiar circuits to become active, patterns that are practiced become quite literally the “path of least resistance.” In many ways, the brain is an energy conservation machine: it uses 20 to 25 percent of the body’s cellular energy (while comprising only 2 percent of the body’s total weight), so there have been strong evolutionary pressures for the brain to be as efficient as possible. Just as water will flow through a well-worn riverbed instead of carving a new path into the bank, when the brain is faced with a choice between two actions, the one that is familiar, that has been repeated, will win out because of its energetic favorability.

It is not difficult to see how these findings relate to the idea of karma. What’s essential in this process is that each of our experiences—thoughts and ideas, emotions and sensations, behavior in the world—is reflected at a cellular level. Millions of neurons come alive in a complicated network of activity that underlies each experience. And to the extent that these specific patterns of activity are repeated, the neural connections are facilitated—the mental grooves deepen. As a result, engaging in any particular thought or behavior will make us more likely to engage in the same action in the future, as every act reinforces the neural connections that are associated with it.

Viewed from one side, this can be seen as energy conservation or simple biological cause and effect; from another side, this is the law of karma playing out in our daily lives. In a very literal sense, what we think, our brains become. The karmic aspects of neural plasticity have important implications. Buddhism says that at the heart of suffering is ignorance and delusion—our inability to see the true nature of reality. Instead of seeing the impermanence and emptiness of all phenomena, we tend to view things as independent and stable, imbued with an essential nature. We reify the objects and people around us, making them discrete, separate, and assigning them inherent identities. Most of all, we take the same kind of concretized view of ourselves. This mistaken view of reality is the cause of dukkha, leading to an unending stream of desires and aversions aimed at satisfying and protecting our sense of self.

Related: The Science Delusion

The brain’s capacity for neural plasticity facilitates this delusion, and it does so through the neuronal associations that contribute to concept formation. To examine one model of the process, consider this example of a basic visual stimulus (adapted from Thomas Lewis, Fari Amini, and Richard Lannon’s A General Theory of Love). Imagine a young girl just learning the alphabet. She encounters the capital letter A for the first time, and it happens to be written in an ornate font. Upon seeing the A, a particular set of neurons in her visual system becomes activated. In the next alphabet book, the A has an apple at its base. In this case, another set of visual neurons will become active— many of the same neurons as for the first A (because of the similarities of the stimuli), and some different (because of the minor differences in font and appearance). In the third instance, the A is again slightly different, causing another group of neurons to activate, many of which overlap from the previous instances.

Each time the child sees another instance of the letter A, the neurons representing the common elements are repeatedly activated, and become more strongly connected following Hebb’s law. Here the common elements are two slanted lines connected in the middle with a horizontal line. According to this model, with repeated exposure the brain naturally extracts the common elements of the visual stimulus, leading to a concept of the letter A. Later, that concept becomes elaborated, incorporating the sound and function of the letter in a word, and so on. Eventually, when the girl sees two slanted lines connected by a horizontal line, the hardwired neural A pattern will immediately activate, allowing her to recognize the letter and interpret its meaning effortlessly.

Conceptual processing is extraordinarily functional in terms of our ability to operate in the world and interact with others. Concepts are central to the way the brain learns and remembers. Without them, we’d be baffled by the simplest tasks, endlessly examining an unfamiliar item such as a spoon or a pen and wondering what we should do with it.

But concepts also have a shadow side: by their very nature, they distort our perception. In fact, this has been long recognized within Buddhism. For example, as the American scholar John Dunne has pointed out, the philosopher Dharmakirti (c. 7th century) claimed that repeatedly encountering a unique instance of an object will lead to a “false awareness” that emerges because we construct a “sameness” (a concept) for a class of objects that is pertinent to our immediate interest. Because of the concepts we hold, we don’t see the uniqueness of a given instance of that object. Instead, we believe that the concept we have of it represents its fundamental essence.

The idea that concepts distort our experience is also supported by modern cognitive science. For instance, in the alphabet book example, the neuronal activations related to the differences between instances of the letter A are not reinforced because they are not repeated: this is the flip side of Hebb’s law. Thus, because only the common elements of the letter have been reinforced, when the girl sees an A, the neurons involved in processing those common elements will be activated much more strongly than the neurons representing the individuality of that particular letter. In effect, she actually does not perceive the unique elements of the stimulus as much as the common elements, because those neurons are not as strongly connected to the network. Perception becomes distorted; the true nature of the world becomes obscured. The conceptual filters in our mind construct a veil over reality.

We don’t see interdependence and impermanence, because we crystallize everything into discrete preformed patterns that seem stable over time. We don’t see emptiness, because we believe our concepts represent some true essential nature. It seems that a certain arrangement of lines is inherently an A, and will always be so. In the case of recognizing a letter, this may not be so problematic. However, the same process leads to the narrow labels we apply not only to objects but also to people. The result is our inability to truly perceive others (or ourselves) in the uniqueness of each moment. Thus viewed, delusion—our misperception of the world—is part of the natural result of a fundamental biological process, one that is beautiful in its elegance and utility, but also dangerous in its capacity for distortion.

Where does this leave us? Are we doomed to play out our lives at the mercy of our habitual neural patterns? Both Buddhism and modern neuroscience say no. In fact, the neuroplastic capacities of the brain that contribute to our karmic limitations become the same ones that hold the key to our liberation.

For centuries, the experiences of contemplative practitioners have shown that transformation is possible. More recently, neuroscience—in part because of its engagement with Buddhism—has discovered a previously unknown potential for brain plasticity throughout one’s lifespan. This is the good news: with repeated practice the brain can be changed, and to a surprising degree. Indeed, because neural plasticity is always operative, the brain is continuously being “rewired” based on our experiences. The key is to put some conscious intention into what those experiences are.

Through repeated meditation practice, we can build awareness of our existing mental habits. With awareness, there is space—allowing us to interrupt habitual response patterns and bring intention to our responses, choosing to form a different association. In time, we can begin to carve a new path into the riverbank.

This process is not an easy one: we are working against deep mental grooves that have been reinforced thousands, if not millions, of times. Competing with hardwired patterns takes a lot of energy—meaning both effort and the cellular energy needed to support synaptic remodeling. This is the physical correlate of purifying our karma and the first step toward revisiting social patterns and collective karma, which extend far beyond our own lifetimes.

Although the work can at times be mentally and physically exhausting, we should take heart. As new pathways are laid down, the old ones begin to weaken from lack of use. This knowledge can give us encouragement: Change is indeed possible, but it’s also normal for the process to be difficult. We gain patience when we understand that it will take many repetitions of a new thought or behavior to carve out a different avenue for neural function. With dedication, we can slowly build healthy mental tendencies, for awareness and wisdom, for kindness and compassion. That’s why we practice.

As for transcending delusion, whether and how we can ultimately change the way concepts reify our experience is an open question for neuroscience. Traditional Buddhist accounts, as we know, do speak to the possibility of a direct experience of emptiness that is beyond concepts.

Biologically speaking, we will likely never completely “undo” the physical manifestation of our mind’s conceptual structures. After all, we need our concepts to act meaningfully in the world. However, awareness can shape the way we relate to our concepts, allowing us to see them for what they are. With study and practice, we can move beyond our reductive thinking, lifting the veil to reveal the true nature of reality.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.