The iconography is very powerful, or perhaps by now I am overwhelmed by the collective impact of five days of monasteries and am a little churched out, or maybe it’s the altitude, but suddenly everything begins to act on me, to become alive: the horrific statues of the Drakpo Lah, the wrathful deities with blue faces and bared fangs who are often protectors of the dharma and represent the hell realm; the writhing figures of green-limbed deities with consorts on their laps entwined in wild tantric sex. Everything begins to move. It is very disquieting, like a bad acid trip, or a foretaste of Bardo, which is what Timothy Leary compared the LSD experience to, and which a Western practitioner in Kathmandu described to me as “your own mind’s projections completely unleashed, like pieces of paper in a hurricane for those who haven’t learned to meditate and rest in emptiness.” The least desirable of the six kinds of beings that your consciousness can be cycled into is that of the Hungry Ghosts, who have huge stomachs and pinholes for mouths and to whom food tastes like blood or pus. It is the destiny of those attached to material possessions, the Trump realm. When I described my experience several days later in Kathmandu to Chogyinima Rinpoche, he laughed and said, “Tibetan Buddhism is Disneyland. But because you experienced it, it exists.”

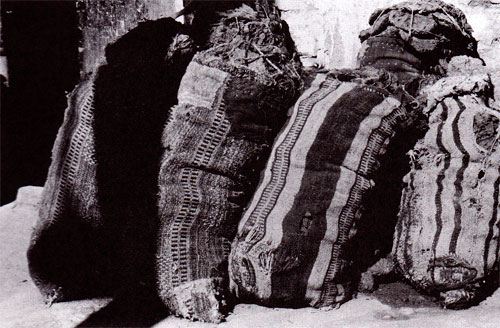

There is finally a flurry of action in the sentient being department: a musk deer bounding through boulders; further on, a lone, undoubtedly German inji, as Westerners are called in Tibet (from Englishman), standing on the pedals of a mountain bike weighted down with gear; then two Tibetan wolves, followed a mile later, picking its way furtively up a scree slope, by a Tibetan fox, salmon-red on top with agouti-gray flanks and tail. We drop in on a family of drokhpa, who are camped in a black felt tent beside a stream from the glaciers.

The man is stitching the sale of a sneaker belonging to one of his six kids. Beyond smoke rising from an open yak-chip fire through a hole in the roof, I notice a small shrine with pictures of the Buddha and Sakya Rinpoche. Rinchen gives the woman a snapshot of the Dalai Lama, and she presses it to the crown of her head to receive its blessing.

I asked about the Tibetan belief that very soon the forces of darkness will destroy the dharma, and eventually themselves, everywhere on earth except for one secret place, called Shambhala—the Shangri-la in James Hilton’s Lost Horizon—after which the sages holed up there will come forth and usher in a new age of unprecedented harmony. Are we in this dark age now? There is certainly plenty of evidence of darkness.

I combed the landscape in vain with my binoculars for lamas lung-gompa, the bounding trance-walkers who were supposed to have been a rare fugitive part of the landscape in Old Tibet. Masters of lung-gom, or wind-air meditation, these advanced practitioners were supposedly able, by filling themselves with “internal air,” to become nearly weightless, like balloons. They could levitate and even fly short distances, and run a hundred miles in great leaping bounds like gazelles, without stopping, in a deep trance that couldn’t be disturbed or they would instantly die.

I had been thinking about the relation between inner balance and planetary balance, about how, if each of us could be at peace and in harmony with himself, the outer world would take care of itself. There would be no war, and the trashing of the environment would be minimal. Conversely, as Son Am had put it in Kathmandu, “You imbalance nature, you got to be the victim.” “Buddhism preaches against attachments,” I said, “and national attachments have been responsible for much of the evil in the world. Furthermore, if nothing is real, then Tibet isn’t real, so what’s the big deal? Isn’t there a contradiction here?” His Holiness smiled appreciatively. “No contradiction, because things don’t exist independently. They have the ability to be changed, so it’s worthwhile to make the attempt. Everything depends on one’s own action.”

We visited a cave where Milarepa, the famous twelfth century yogin-mystic-poet-saint, once spent nine years. To avenge his destitute widowed mother, who had been cheated out of her inheritance by her brother-in-law, Milarepa learned black magic, through which he effected the collapse of his uncle’s house on him and everyone inside. Then, to atone for his sin, he went to agreat teacher named Marpa, who directed him to build a series of towers, after which Marpa, a disciple of the Indian yogin Naropa, initiated him into the secrets of Tantra. Milarepa mastered tummo and lung-gom meditation, and also dream meditation (in which one sees the future). There are many tales about his amazing feats. Once, for instance, caught out in the rain with his disciple Rechumpa, he took shelter inside a cowhorn—without shrinking or making the horn bigger.

Turning to the concept of shunyata, or “emptiness,” the view that everything is imputation, a projection of the mind, and lacks intrinsic reality, I told the Dalai Lama how, the other night, I had gotten up and tripped over a suitcase that I had left in the middle of the floor. How could the suitcase have been all in my mind, when I had completely forgotten it was there? He laughed. “What is a suitcase? You can describe the color, shape, size, weight, and material of the suitcase, but still there is something else. At the quantum mechanical level, there is no suitcase. And besides, if you were a sub-atomic particle, you could pass right through the suitcase. Both the suitcase and yourself, if you analyze, you cannot find their independent existence. But that does not mean that they do not exist at all.”

♦

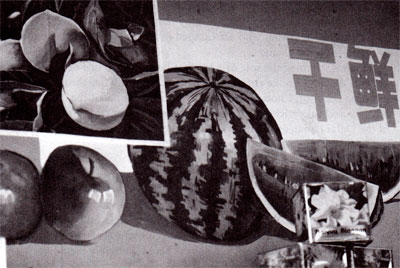

Artist Robert Rauschenberg visited Tibet in 1985, for the opening of the Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange Exhibition at the Tibet Exhibition Hall.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.