For poet Ocean Vuong, the act of writing is inextricably linked to his Zen Buddhist practice. In a 2022 episode of Life As It Is, he told Tricycle’s editor-in-chief, James Shaheen, and meditation teacher Sharon Salzberg that he believes the task of the writer is “to look long and hard at the most difficult part of the human condition—of samsara—and to make something out of it so that it can be shared and understood.”

Now, in his new novel, The Emperor of Gladness, Vuong turns his attention to our cultural avoidance of illness and death, as well as the small moments of care and kindness that are essential to survival. Tracing the unlikely friendship between a young writer and an elderly widow who’s succumbing to dementia, the novel reckons with themes of history and memory, loneliness and heartbreak, and failure and redemption.

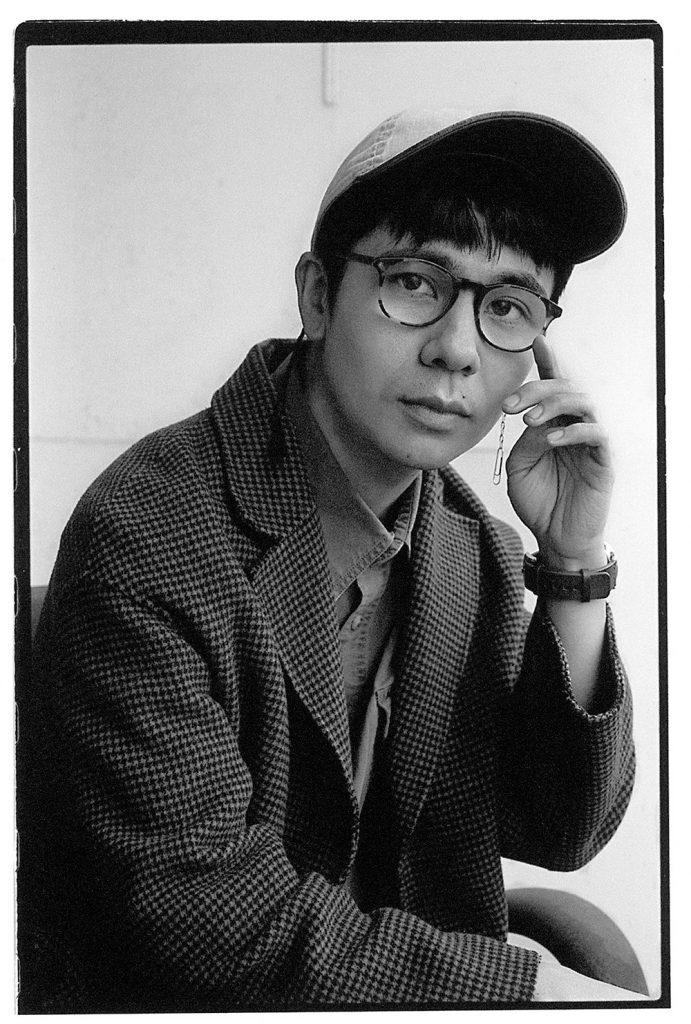

In a recent episode of Tricycle Talks, Tricycle’s editor-in-chief, James Shaheen, sat down with Vuong to discuss how he incorporates Buddhist notions of emptiness and nothingness into his writing, the role of ghosts and the dead in his work, how writing can be a form of prayer, and what he’s learned from Buddhist understandings of redemption.

To start, can you tell us a bit about the book and what inspired you to write it? I’m always thinking about death, perhaps in the Buddhist sense. My whole life has been informed by intergenerational relationships, and I’ve noticed that in our culture, the very young and the very old are kind of pushed toward the fringes of society. They’re no longer in the center. The young are deemed to not have enough experience to contribute, and the old are deemed defunct. And I think the relationship between that, the foundation between that, is an immense loneliness between those two poles of our society. To me, the tension and the common ground between those spaces is fertile soil to write about not only human life but human troubles: What good is hope when there’s no point of it, when it doesn’t drastically change your life? I don’t have any answer, per se, but I’ve always been haunted by those questions.

The book begins with a haunting description of the town of East Gladness, Connecticut. Could you speak to the juxtaposition of abundance and decay you describe and why you chose to open the book that way? I’ve always wanted to start a book in a way that only a novel can do. And so I have this long seven-page opening that becomes a painstakingly detailed portrait of this town, describing its history, the decay, and the life shooting through the decay. I wanted to just sink into a time-lapse description, because I think description is autobiographical. There’s so much revealed in who we are by how we describe things. What does it say about a person who describes stars as exit wounds?

This also goes back to Zen. Whitman famously asked, “What is the grass?” And in Zen, we have to kind of undo grass. We have to forget grass to see more of it. We have to forget the terminologies. And so I wanted to sink into the descriptions but also forget story or suspend story for a while. We always think the novel should tell the story. But the word narrative comes from the Latin root narus, which means knowledge. To narrate is also to give knowledge, and static description is just as propulsive to me as plot. That was the aspiration, and I hope readers will be drawn into this little town.

Well, the descriptions are fantastic, and the world you describe is a haunted one, with the ghosts of history and memory lurking throughout. Could you say more about the role of ghosts and the dead in your work? I think history is haunted. One of my favorite theorists, Mark Fisher, borrows from Derrida, and he talks about hauntology. He proposes that everything we touch in the material present has a history. You know, you drink a bottle of water. Where are the plastics made? What is the runoff? Does it run into a river, which is then harvested and poured again into the bottle? Whose river is it? Who lived there? Who was killed to possess it? Who is it poisoning? Who is it denying? Who doesn’t get access to it? I mean, that’s one bottle of water. And of course, if we live like this, our heads will probably implode on a daily basis. But a novel offers an alternative way to see time, and so the novelist gets to control where we focus, where we zoom in and out. To me, the hardest thing to zoom in on in a novel is history, and yet when you do so, it keeps giving. I think there’s never a place that is unexamined that doesn’t have a haunted portion of it.

There’s so much revealed in who we are by how we describe things. What does it say about a person who describes stars as exit wounds?

Fisher also talks about the eerie and the weird, and he says something really unique, where he says the eerie is presence that fails to manifest. He talks about ruins behaving this way or forests without leaves. So there’s this gesture toward capacity, toward presence, that fails to manifest. And then I thought, well, isn’t that sunyata? Isn’t that nothingness? Is nothingness eerie? I don’t know yet, but it’s a new thought.

I think, for me, the eerie is very potent. I’m always drawn to it. I don’t turn away from it at all. When you see ruins, you want to walk up and touch them and run your hand through them, right? That’s presence that fails to manifest. In the heart of eeriness and discomfort is a kind of ultimate generative possibility in the Buddhist sense. I haven’t worked that out yet completely, but there’s something there. I’m just trying to lean into that.

In this book, the characters are haunted by war—Hai’s family by the Vietnam War, Grazina by the atrocities of the Second World War. At a certain point these wars start to all blur, and Hai responds to Grazina’s fading memory by going back into the past with her and creating new narratives of survival. So can you say more about how these characters find meaning in different stories of struggle? What Hai realizes is that dementia is its own world, and the reality is that people with dementia can’t choose which world they’re in. Having friends and relatives who lived through that, I’ve seen it firsthand, that they are literally thrown. They are ejected from the present into an elsewhere. And sometimes it’s not the past; it’s truly an elsewhere, which is then reminiscent of the bardo, or this idea that when the consciousness is out of body, the body is no longer stuck in time and space, and it becomes this kind of hyper-hallucinatory, pyrotechnic, kaleidoscopic horror, in a way.

What I’ve noticed with folks in dementia is that they’re actually heading there sooner than we are. The body, with the physical neurons and the holes in the brain with frontal-lobe dementia, is creating a kind of other consciousness. I wanted to have a character meet the person there, because if someone can’t choose where their memory is, then you have to go there with them. That, then, becomes a meditation on fiction, on storytelling: What is real? What is unreal? What is a hallucination? And then you arrive again at a very Buddhist center, which is a Buddhist phenomenology: What is the real, and is it all just a projection of the self? The particular is the universal manifested through perception. At the end of it, everything comes back to my understanding of Buddhism.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity. Visit tricycle.org/podcast for more.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.