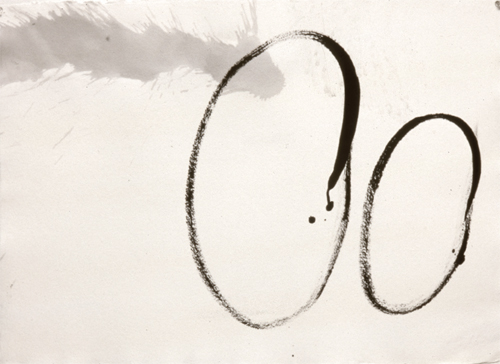

The set of poems and drawings known as the Oxherding series presents a parable about the conduct of Buddhist practice. In the most common version, attributed to a 12th-century Chinese Zen master, there are ten drawings, the first of which shows a young herder who has lost the ox he is supposed to be tending. In subsequent images he finds the ox’s tracks, sees the beast itself, tames it, and rides it home. In the seventh drawing the ox disappears: it “served a temporary purpose,” the accompanying poem says; it was a metaphor for something, not to be mistaken for the thing itself. The herder too disappears in the next drawing; the image simply shows a circle (Japanese, enso), a common symbol for enlightenment. The ninth drawing implies that the person who has achieved enlightenment does not then retreat from the world; called “Returning to the Roots, Going Back to the Source,” it usually shows a scene from nature. The final drawing shows a chubby fellow with a sack “entering the village with gift-giving hands.” Presented here are the painter Max Gimblett’s new versions of the traditional drawings, along with fresh translations of the classic poems. —Lewis Hyde

To read Lewis Hyde’s “One Word” and “Spare Sense” versions of these poems, click here.

I: Searching for the Ox

Alone in the deep woods, despairing in the

jungle, searching in darkness!

Flood-swollen rivers, mountains beyond

mountains, the trail endless and

unchanging.

Bone-tired, heart-weary, the whole thing seems

hopeless.

No sound but the evening cicadas singing in a

grove of maple trees.

II: Seeing the Traces

In the woods, along the riverbank, strange

marks all around.

What has bent the sweet grass down just there?

The deepest canyons, the highest peaks—nothing

can hide that constellation, the Nose of the

Ox

III: A Glimpse of the Ox

The meadowlark sings, sitting on a branch.

Warm sun, light breeze, green willows by the river.

The Ox stands right there; where could it hide?

Splendid head, stately horns, who could sketch their likeness?

IV: Catching the Ox

He must hold the rope with all his might

for the Ox is two-thousand pounds of old habit.

One moment it runs to the high meadows,

then gets lost in fog-bound riverbottoms.

V: Taming the Ox

If he doesn’t keep the whip and rope near at

hand

the Ox will soon find out the nearest muddy

wallow.

But—care for it properly and it becomes

gentle, clean,

following the herder willingly, the rope gone

slack.

VI: Riding Home

He is riding home but seems to be in no hurry.

Evening mist absorbs the flute tones. Their

harmony

carries his heart to the horizon line.

Talk about grass is not what keeps this Ox

alive.

VII: Ox Forgotten

He could not have gotten home without that

animal,

but oh, the Ox has disappeared and the man sits

by himself, content.

His reverie does not bear the red mark of solar

time.

The rope and whip lie forgotten under the cabin

thatch.

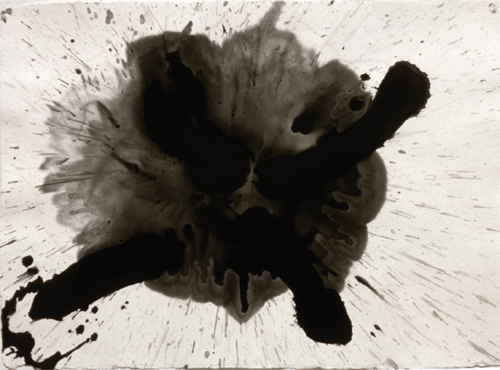

VIII: Self and Ox Forgotten

Empty whip, empty rope, empty Ox, empty

human being.

“The vast blue sky” is not at all the vast blue

sky.

Think of snow falling on a blazing fire. Just

there

the spirit of the ancient masters is fully

present.

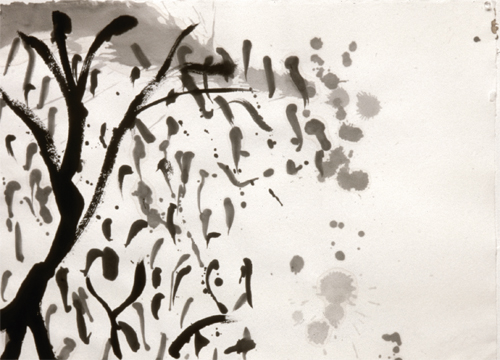

IX: Going Back to the Beginning

Seeking the Source, the One True Origin: why

all this hard work?

Better to stay at home as if ears and eyes had

never opened.

He sits in the cabin. There is nothing to hunt

for beyond the gate.

The streams flow and flowers open, vividly red.

X: Entering the Village with Helping Hands

Barefoot, bare-chested, he walks into town.

Dusty, spattered with mud, how broadly he

grins!

He has no need of magic powers. Near him

the withered trees come into bloom again.

♦

Read an exclusive interview with Max Gimblett and Lewis Hyde here.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.