The taxi brakes and swerves as I struggle to read the finely printed map in my Chinese “Communication and Tourist Atlas.” Dong Shan Temple is indicated, but the map shows no road that leads to it. We’re traveling west from Nanchang City in China’s Jiangxi Province. A hundred miles north from here, at Jiujiang City, the Yang-tse River is cresting at its highest recorded levels of this century. In this region, too, the effects of the ongoing monsoon are dramatic.

But today, the sun shines sporadically between low, water-heavy clouds. Taking advantage of the break in the weather, farmers are piling freshly cut rice paddy, wet from the heavy rains, on the highway to dry. They position wooden logs in the road to protect the rice stalks from the traffic. It’s against state regulations, says my driver, but they “mei you ban fa,” (They’ve got no choice).

According to the Complete Guide to Buddhist America, there are now more than 400 Mahayana meditation centers in the United States, most of them with roots in the Zen tradition. But despite this growing interest in Zen, the historiography of the tradition and its most famous existing Chinese landmarks remain unknown to the West. Dong Shan is the fountainhead of the Caodong (Japanese Soto) School. Yet I was unable to find direct evidence of any visits to Dong Shan by American practitioners. Even Chinese Buddhist sources about the temple’s location are sketchy.

On the road to Dong Shan, a confusion of cars, buses, trucks, motorbikes, and small tractors weave, at different speeds, through a small army of obstacles. A pig wanders onto the narrowed roadway. We squeeze between it and a stack of bright red Jiangxi peppers. We stop as a peasant girl in pigtails appears amid the traffic, herding a buffalo. She coaxes its ageless saunter by lightly slapping its ribs with a bamboo rod.

The water buffaloes are magnificent animals. Their docile grace and good nature are a counterpoint to the brutish mechanization of the Chinese countryside. When not working, they often rest tethered to trees on the flanks of roads, where the uncultivated land and trees offer grass and shade. In Zen parable and poem, these beasts symbolize service to others.

One day Zhaozhou asked Nanquan [Japanese: Nansen], “Where do people with knowledge go [when they die]?”

Nanquan said, “They go to be water buffaloes down at the Tans’ and Yues’ houses at the base of the mountain.”

We enter a country town named Shangfu, where the streets are lined with neatly stacked piles of watermelons. At the bustling main intersection we ask directions. Dong Shan is somewhere straight ahead. As we set off from the town the quality of the road drops dramatically. We bounce along, and I watch the farmers perform their summer activities. They work knee-deep in rice paddy mire, cutting and harvesting, ploughing and replanting. Their paddies lie interspersed with unusually steep hills covered by dense underbrush, timber bamboo, and Chinese firs. The steaming July heat weights the thick vegetation.

Deep in the hills, we arrive at an impoverished village. Some of its distressed buildings look near collapse, and the few inhabitants we see seem languid and dazed in the midday heat.

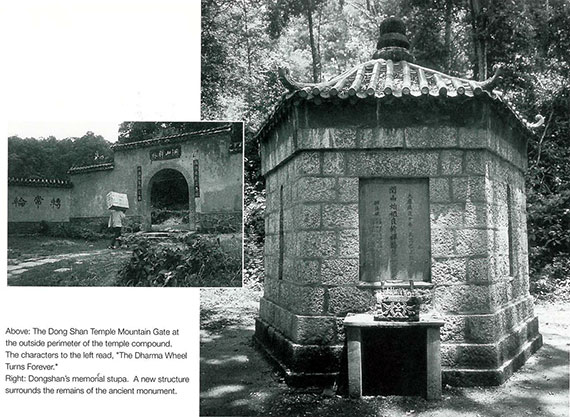

Right:Dongshan’s memorial stupa. A new structure surrounds the remains of the ancient monument.

Soon, we stop before a steel-grated gate. At its right is a squat brick guardhouse. The old attendant looks bewildered at the sight of the taxi and its strange passenger. We pay an entrance fee. The gate swings open, and we proceed slowly over the jagged rocks for a short distance until the road abruptly ends. We are in the precincts of the temple, but there is no sign or other indication that we are close to the source of Dongshan’s Zen. We park, take our packs, and walk up the path into the woods.

The sound of a creek spreads through the verdant undergrowth, and I remember an ancient koan.

Longya asked Dongshan, “What is the essential meaning of Zen?”

“I’ll tell you,” said Dongshan, “when Dong Creek flows uphill.”

At these words, Longya realized enlightenment.

After a hundred meters we cross the stream on a handsome gray bridge. Farther along, two water buffaloes stand in a branch of the stream. A monk comes up the trail behind us toting a large cardboard box with the words “electric fan” on the outside. We let him pass, then follow him into a mountain valley of rice paddy. Nestled at the rear of the valley is a small, dignified looking temple.

The Caodong School of Zen is one of the “Five Houses,” or five classic Zen schools. Its name is derived from two “mountain names,” one from the founder of the school, Dongshan Liangjie, and the other from his famous disciple, Caoshan Benji. Caodong Zen survives, along with the Linji (Japanese: Rinzai) School, as one of the two remaining ancient Chinese Zen schools.

The founder of the school, and the temple we are visiting, was Zen master Dongshan Liangjie (807�69). According to traditional stories, he displayed highly unusual abilities as a youngster and young man. Early in his travels he visited various Zen masters, including Nanquan.

Eventually, Dongshan studied under Yunyan Tansheng. Despite years of effort, Dongshan’s understanding of Zen remained incomplete. He decided to leave Yunyan and continue his journey in search of the Way.

Just when Dongshan was about to depart, he said, “If in the future someone happens to ask whether I can describe the Master’s truth or not, how should I answer them?”

After a long pause, Yunyan said, “Just this is it.”

Dongshan sighed.

Then Yunyan said, “Worthy Liang, now that you have taken on this great affair, you must consider it carefully.”

Dongshan continued to experience doubt. Later [on his journey] he crossed a stream. He looked down and saw his reflection in the water. Suddenly he awakened to Yunyan’s great meaning. He then composed this verse:

Avoid seeking elsewhere, for that’s far from the Self,

Now I travel alone, everywhere I meet it,

Now it’s exactly me, now I’m not it,

It must be understood this way to merge with Thusness.

The path jogs to the right and comes to a faded red Mountain Gate. Over the passage a sign says “Dong Shan Monastery.” Black Chinese characters to the left proclaim, “The Dharma Wheel Turns Forever.” We follow the monk on a path along a rice paddy to the entrance of the temple compound. There, above an entrance gate, a sign reads “Caodong Ancestral Grounds.”

The layout of the grounds follows a standard pattern of Chinese temple construction. Three rectangular temple buildings succeed one another. A visitor enters the central entrance of the first hall and exits the rear to face the entrance of the next building and so on. The first building at Dong Shan is a traditional “Tian Wang Dian,” or “Hall of the Celestial Kings.” Entering the door, a statue of corpulent Maitreya Bodhisattva, the future Buddha, sits at the center of the hall facing the entrance. Flanking the outside of the hall, two on a side, are four colorful deities. These are four celestial kings—deities who protect the four continents that flank mythical Mt. Sumeru, the center of the universe. They are the Dharma generals of Indra, the Emperor of the Gods in ancient India.

The second hall of the temple is the Daxiong Baodian, or “Great Hero Treasure Hall.” This name is commonly applied to Buddha Halls at Zen temples throughout the country. In ancient China, the name “Great Hero” was applied to the Buddha. Facing the entrance sits a bronze Amida Buddha on his lotus throne, flanked by attendants, his right hand raised in greeting, its fourth finger lightly touching the thumb. At the sides of the hall are figures of the sixteen True Dharma Protecting Arhats. At the left rear, the bodhisattva Samantabhadra rides majestically on a white elephant, and at the right, Manjusri sits astride his lion. Directly behind Amida, a thousand-armed Guanyin statue gazes toward the rear of the hall. Following her gaze, we go out into the courtyard of the “Wisdom Spring.” Here we find a spring of pure, clear water that flows in a cistern at the heart of the grounds. Its central location implies that the layout of the temple has remained unchanged since its construction during the Tang Dynasty (circa 750 C.E.). The spring continues to provide the fresh water that sustains the monks as well as local inhabitants who seek its curative powers.

Finally, the Dharma Hall, which, at 300 years old, is the oldest of the existing buildings. Its broad red facade is weathered but intact, and it recalls a measure of the temple’s graceful ancient demeanor. This structure stands where Dongshan lectured. Here he engaged his monks in the symbol-laden dialogue that the classical masters used to test their students’ understanding.

We are greeted by a handful of monks who have noticed our arrival. They are surprised to see us and immediately invite us to join them for the noon lunch that will be served shortly. We accompany them up some stairs in the Dharma Hall to a small meeting room. There, the new electric fan that came up the trail provides some modest relief from the heat, and a monk named Chun Shan (“Pure Goodness”) introduces himself.

Chun Shan explains that he is a student of Zen Master Cheng Yi, the abbot of Yunju Shan. That monastery, located northwest of Nanchang City, was founded in the ninth century by Zen Master Daoying, the second-generation Dharma heir of Dongshan. Yunju Shan is one of four or five major Zen practice centers that are again active in China. Chun Shan has moved from Yunju to Dong Shan to help restore the site after decades of neglect.

Before lunch is served, we take a short walk to Dongshan’s memorial stupa. It is behind the Dharma Hall, a few meters up the hill to the left. As we approach it is completely concealed in the forest canopy. Behind the foliage we find a six-sided, white-brick, masonry monument resting on a sculpted terrace. It is adorned with a red tiled roof that is topped by a round globe. Inscribed in its front alcove are red Chinese characters that read “The Founding Ancestor Zen Master Liangjie’s Wisdom Awakening Precious Pagoda.” Other characters list the founder’s main disciples and date the original stupa in the tenth year of the Xian Tong era of the Tang Dynasty, or 870 C.E..

At the rear, a grated steel door allows a view of the original ancient stupa, now concealed and protected within the newer structure. It resembles an ancient marble stone lantern with six sides. At its base are Buddhist swastikas. The upper portion of each side was once inscribed with lotus flower relief and Chinese characters, but now nearly all portions are worn away or destroyed. At the top of the small stupa is a round globe. I’m reminded of the story on Dongshan’s death.

A monk asked, “When the master is not well, is there still someone who is well, or not?”

Dongshan said, “There is.”

The monk asked, “What does the master see?”

Dongshan said, “When I observe him, I don’t see any illness.”

Dongshan then said to the monks, “When you leave the skin-bag you inhabit, where will you go and see me again?”

The monks didn’t answer. Dongshan then recited a verse:

Students as numerous as sands in the Ganges but none are awakened,

They err by searching for the path in another person’s mouth,

If you wish to forget form and not leave any traces,

Wholeheartedly strive to walk in emptiness.

Dongshan (later) returned to his room, and, sitting upright, passed away. It was the third month [in the year 869 C.E.]. He received the posthumous name “Enlightened Source.” His stupa was named, “Wisdom Awakening.”

The quiet solemnity and significance of this ancient site weighs upon me. Paying homage, I sense its spiritual force. I think of the countless monks and individual stories that come from this one story; the countless Dharmas that come from this one Dharma. This sacred spot seems warmly supported by the earth and sweetly protected by the forest. For centuries it has been enough to stay right here; to remain silent; to remain unmoving.

Lunch is served in the small dining hall set in a garden area twenty meters from the main compound. A gracious woman cook has set out platters of tofu and vegetables, plus a condiment dish of fiery hot chillies. My driver and I eat silently at our own table. On the whitewashed stucco wall of the eating area is a vertical red sign with four black Chinese characters that read “Everything Fully Complete [and] Perfect.”

After lunch we meet again with the monk Chun Shan in his quarters in the Dharma Hall. “We seldom get visitors here from abroad,” he says. “A few Japanese have come, but as for Americans, I think you’re the first.”

We exchange observations about Zen practice in our two countries, and I find him keen to understand the current state of Zen in America. “In China now,” he says, “many places are just empty shells. They have some outside appearance, but inside there’s no soul. If you go to Yunju Shan, you’ll see a place where the external appearance and the internal soul are both still there.”

Chun Shan explained about the life of Yunju Shan monks. The monks normally arise at 4:00 A.M. and prepare for a one-and-a-half-hour period of sutra chanting. At 6:00 A.M. they eat a small breakfast of rice gruel or steamed bread, then continue their practice with two hours of meditation. Thereafter, a larger group of monks performs temple work while a small group continues sitting in meditation. After lunch and in the evening, zazen continues, with varied times of kinhin (walking meditation) scheduled as well. Generally, all monks perform four two-hour sessions of meditation each day. In the winter, the amount of zazen is increased.

As the afternoon goes on, Chun Shan and I talk in detail about the development of Zen in America. He expresses interest and concern about the methods used to teach Zen in our country. “In America, many people read books about Zen,” says Chun Shan. “I think American Zen is mostly what we call ‘wen zi Chan’ (literary Zen). This teaching incorporates a lot of reading and also the study of koans, and so forth. In China,” he continues, “there was a period of several hundred years after the introduction of Buddhism before Zen appeared. That early period was also a literary period for Chinese Buddhism. At that time, before the arrival of Bodhidharma, the sutras and shastras were read and studied.”

Chun Shan is worried about the future of Zen. He is not optimistic that sufficient numbers of genuine Zen adepts will appear to carry on the tradition. Despite recent gains, his viewpoint on Zen’s future is pessimistic, based on bitter experience. “In America,” he says, “if Zen teachers bring forth teaching from the true Mind-Ground of Zen, then America will be able to develop its own new style of Zen culture. If it is just an imitation, then it cannot be successful.”

In late afternoon we end our discussion. We stand looking across the precincts of the temple from a top-story window of the Dharma Hall. I’m struck by the beauty of the new green sprouts in the rice paddies. Long ago, from this vantage point, these fields met the gaze of the founder and famous monks of our tradition. Seeing Dong Shan Temple attempting to arise, phoenix-like, from the ashes of the Cultural Revolution, I lose my uncertainty about engaging with Chinese society.

As we say our good-byes and make our way toward the gate of the temple, one of the monks appears with a small box.

“This is a gift in commemoration of your visit,” he says.

I accept the gift of a beautiful ornamental bowl. After a final photograph, we wave goodbye and begin our return to Nanchang.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.