A shooting star, a clouding of the sight,

a lamp, an illusion, a drop of dew, a bubble,

a dream, a lightning’s flash, a thunder cloud:

this is the way one should see the conditioned.

—trans. Paul Harrison

This revered verse from the Diamond Sutra points to one of Buddhism’s most profound yet confounding truths—the illusory nature of all things. The verse is designed to awaken us to ultimate reality, specifically to the fact that all things, especially thoughts and feelings, are the rainbow-like display of the mind. One of the Tibetan words for the dualistic mind means something like “a magician creating illusions.” As my teacher Ngakpa Karma Lhundup Rinpoche explained: “All of our thoughts are magical illusions created by our mind. We get trapped, carried away by our own illusions. We forget that we are the magician in the first place!”

So much of our suffering arises from believing our thoughts, perceptions, and feelings to be accurate reflections of the world and ourselves. We think our thoughts—especially those that make up our sense of self—are substantial and lasting. The truth is that they are not. They are completely illusory. Even our bodies are illusory. We experience them as solid and independent, but they are in fact permeable, interconnected with and dependent on all other things. They are also ephemeral. The only way in which these things reflect so-called reality is that they too are like rainbows, an illusion. We see, hear, smell, and even touch things that are not really there. This is delusion, this is suffering, yet we don’t recognize it as such. We think it is our normal and natural state, but to be so disconnected from reality is indeed a form of suffering. What we sense or perceive as solid, separate, lasting entities, are in fact rainbow-like tricks of the mind, dreamlike illusions that in essence are pure luminous space, or shunyata (Skt., “emptiness”). All our thoughts, feelings, and sensations are the result of the dualistic mind creating a perception of substantial, lasting form that is not truly there. We react to this illusion with attraction or aversion, but if we see it for what it is, we awaken to the ultimate. As the great Indian yogini Niguma (10th or 11th century) taught:

This variety of desirous and hateful thoughts

that strands us in the ocean of cyclic existence,

once realized to be without intrinsic nature,

makes everything a golden land. . . .

If you meditate on the illusion-like nature

of all illusion-like phenomena,

actual illusion-like buddhahood

will occur through the power of devotion.—Niguma, Lady of Illusion, trans. Sarah Harding

So how do we shake off this misperception of reality and ourselves and wake up to our true nature? In Vajrayana Buddhism there is a method called Illusory Form Yoga, or gyulu, which I like to call Rainbow Yoga. The heart message of Illusory Form practice is this: The universe and its contents are dreamlike illusions. Nothing is truly substantial or solid; everything is luminous space. Nothing exists independently; everything is interconnected and interdependent.

To see the illusory nature of things is to be released from our perpetual yearning and fear into a state of relief and joy. If we truly recognize that our experience is already a self-perfected display of the ultimate nature, then we have no need to strive and nothing to do but rest in that perfection. A famous verse by the great Dzogchen master Longchenpa (1308–1364) illustrates this point:

Since everything is but an apparition, perfect in being what it is, having nothing to do with good or bad, acceptance or rejection, one may well burst out in laughter.

—The Natural Freedom of the Mind, trans. Herbert Guenther

To recognize the illusory nature of things means to directly know or experience reality. How is it achieved, this recognition, this deep knowing, of the true, illusory, and dreamlike nature of all things? This is achieved through simple contemplation supported by daily reminders and by our ongoing meditation practice. Take as an example our perception of color.

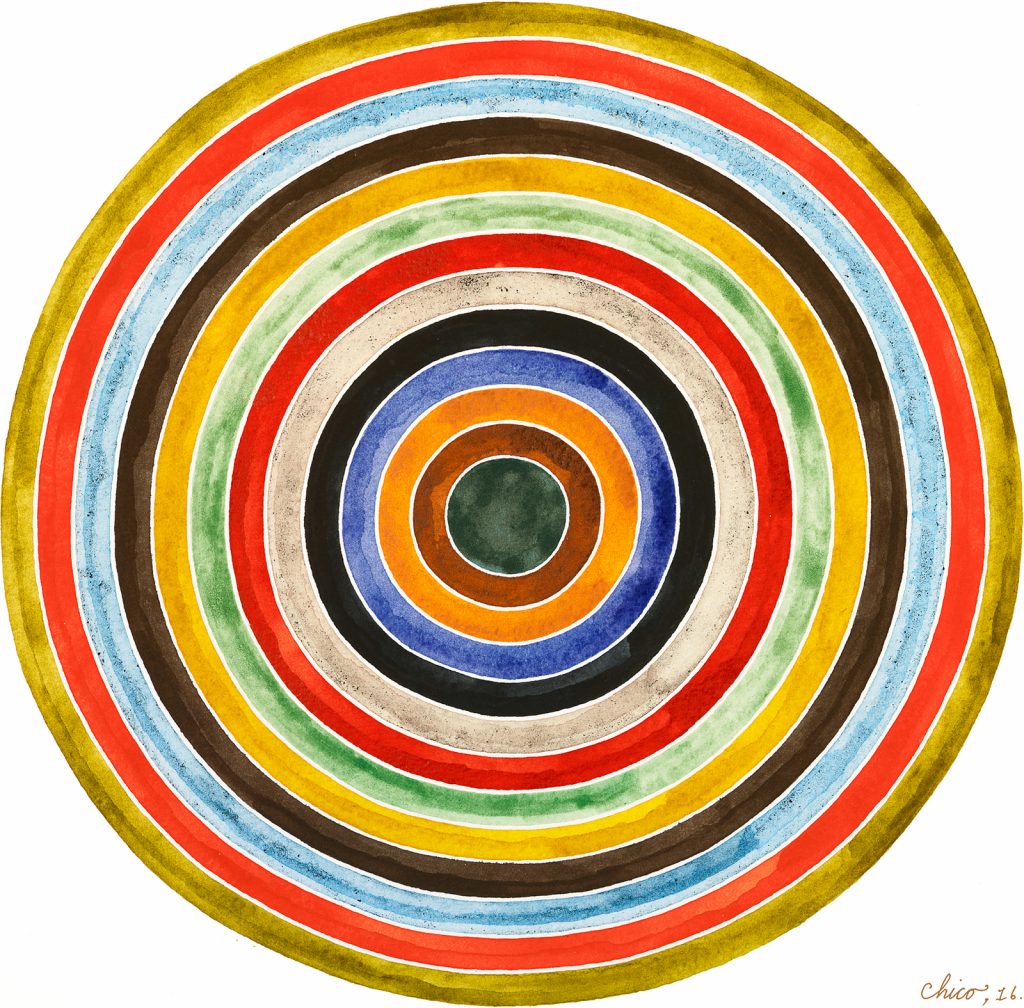

Color is an illusion created by the brain. In reality, physical matter has no color. The sky is not truly blue, grass is not green, and water is translucent but often appears otherwise to us, either blue or green. Our eyes and brain cooperate to create the perception of color where there is none, by interpreting the wavelengths of light bouncing off various objects. Of course, light itself has no color either. Color is a complete fabrication, and yet look at how dominant it is in our world and in our life. Look out the window. Look at your clothes. Indeed, look in the mirror at your own eyes. It’s all an illusion, a mirage. Our perception of the world on this level is a fabrication of the brain. To feel the truth of this, we can make color the focus of our meditation. We find a comfortable seated position and allow our mind to settle. If we usually sit with our eyes closed, we open them and look out with an open, relaxed gaze. Then we turn our attention toward the colors that we see and contemplate the illusory nature of these colors, without engaging in too much verbal thinking. The goal is not to think “These colors are not real” but to directly experience and deeply feel their illusory nature.

This is a dreamlike illusion, a temporary mirage, a fleeting fabrication. Let it go and rest.

In time we will discover that it is not only color that is illusory. Our whole perceptual experience is the result of fabrication between our senses, brain, and dualistic mind. It is very helpful to contemplate this regularly, to understand how we come to see color and shapes, to hear sounds, to taste sweetness or bitterness. Contemplating the way our senses and brain fabricate our experience reveals the dreamlike quality of it all.

To deepen our understanding of illusory form we always undertake contemplation in tandem with sitting meditation or shamatha. We do the contemplation first, then rest in meditation. The contemplations undermine our misperception so that when we sit in shamatha we can more directly experience our world. The silent sitting helps clarify our contemplations by giving us more focus, more clarity and strength of thought, and also brings them home, to the heart. Likewise, the contemplations deepen our meditation by helping us drop our grasping and open up to raw, unmediated experience. It is also helpful to regularly remind ourselves of the illusory nature of things by using a simple aphorism. I use the following:

This is a dreamlike illusion, a temporary mirage, a fleeting fabrication. Let it go and rest.

I repeat this aphorism to myself many times a day, especially at times when I’m feeling emotionally reactive or experiencing strong attraction or aversion. I repeat a slightly different version of it when I notice myself swept up in thought or emotion: Thoughts and emotions are dreamlike illusions, mere fleeting fabrications. Then I let the thoughts or emotions go, by connecting with the breath and resting for a moment. It’s also useful to remember that thoughts and emotions are reactions to illusions, mirages on top of mirages. It is a good idea to write or print the aphorism and place copies prominently in our home and workplace—on our desk, on the fridge, on the bathroom mirror, on our favorite tree in the backyard. It’s especially helpful to put one somewhere near our bed so that we will see it on waking and going to sleep.

If we regularly contemplate the misleading nature of perception and dualistic mind and use an aphorism to remind us of the rainbow-like quality of all things, there will come a time when our very perception changes. We will no longer be hoodwinked by the mirage of misperception. The veil of fabrication obscuring the ultimate nature will drop away, and we will experience reality directly, as it is, in all its luminous perfection. This direct seeing is realization, awakening.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.