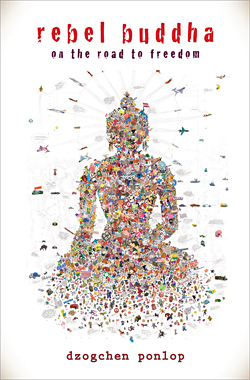

Rebel Buddha:

Rebel Buddha:

On the Road to Freedom

Dzogchen Ponlop

Shambhala Publications, 2010

224 pp., $21.95 cloth

When Buddhism began spreading across the United States in the 1940s and 1950s, we received the bearers of these teachings as good hosts, but our guests were not your garden-variety visitors who would politely marvel at our comfortable and consumptive lifestyle. Nor were our Buddhist guests particularly interested in an easy exchange or in a hurry to get too familiar, too warm and cozy, too soon.

Transmitting Buddhism to America was going to be a slow process. The Rinzai roshi Sokei-an said it would be like “holding a lotus to a rock, waiting for it to take root.” Sokei-an’s approach and attitude were a little rough, even rude: he hung a sign at the West 73rd Street apartment where he taught that said, “Those who come are received; those who go are not pursued.” Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, who was as responsible as anyone for the transmission of Buddhism to America, thought maybe it would take a hundred years to establish his Naropa project, “and we’re not in a special rush.” The early Buddhist teachers displayed a majestic indifference to the fast pace and impatience of American society: it might take a hundred or maybe even three hundred years for Buddhism to take root in America, but they were going to get it right.

Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche’s Rebel Buddha: On the Road to Freedom is the latest attempt to present Buddhism to Western audiences in its most essential and naked form, “a culturally stripped down vision of the Buddhist spiritual journey,” as Ponlop puts it. The book combines two lecture series he gave on Buddhism and culture—one in Boulder in 1999, and another in Seattle in 2008. Both series displayed the same embrace of direct and ordinary language—a freshness of expression and communication that were no doubt partly the result of Ponlop’s having lived almost half of his life in the United States and Canada.

Rebel Buddha contains an introduction to the Buddhist path and some of its methods, but at the same time it opens up larger questions about how to build a practice community and establish a lineage of awakening in the West. Central to Dzogchen Ponlop’s stripped-back Buddhism is an Emersonesque message on self-reliance and the need to recognize the potential for wisdom emerging from one’s own experience. The book orbits around the central image of an inner rebel buddha—“the voice of your own awakened mind”:

It is the sharp, clear intelligence that resists the status quo of your confusion and suffering. What is this rebel buddha like? A troublemaker of heroic proportions. Rebel buddha is the renegade that gets you to switch your allegiance from sleep to the awakened state. This means you have the power to wake up your dreaming self, the imposter that is pretending to be the real you. You have the means to break loose from whatever binds you to suffering and locks you in confusion. You are the champion of your own freedom. Ultimately, the mission of rebel buddha is to instigate a revolution of mind.

That said, the book and the discussions that have followed in the wake of its release are also about an outer revolution, opening questions about American or Western Buddhism’s shifting forms and new needs. The central theme of the book is Dzogchen Ponlop’s conviction about the need to separate the cultural aspects of Buddhism from its central message. It arose out of his own experience, which led him to recognize the “almost blinding influence of culture in our lives and thus the importance of seeing beyond culture altogether.”

So where is Buddhism in America now? Buddhism is everywhere. Buddhism has successfully adapted to its host. It is no longer odd, no longer difficult to find. Buddhism is mainstream. The Dalai Lama won the Nobel Peace Prize; he is a celebrity and the guest of heads of state. In suburbs across American, bumper stickers declare concern for Tibet and Buddhist culture, while Buddhist magazines and quarterlies have spread from the checkout stands in small alternative neighborhood co-ops to big corporate bookstore chains. Buddhist centers of all stripes and sects have taken root in every region of the country. Buddhist publishing has exploded, and the Internet has accelerated access to all things Buddhist, while helping to shape Buddhism itself. In the process of popularization, cultural assimilation, and transformation, Buddhism has become very American. The dharma is no longer a stranger, an unknown guest, but a familiar and comfortable friend.

Dzogchen Ponlop is a gentle voice for this emerging and more accessible Buddhism. He wants to be liked and wants us to feel comfortable meeting him in a café. He delivers lots of one-liners that provide the opening frame for his thoughts. But everything in moderation: Ponlop is part prankster, part hipster. He seems comfortable in the role of the “rebel with a cause,” but in his case, a rebel willing to meet everyone where they live—including those who have one foot firmly planted in the bourgeoisie while testing the waters of Buddhism with the other. Buddhism can be conceptual, broad, open, and ecumenical—and at the same time encourage the relentless zeal and dedication to practice of those who aspire to profound realization. For Dzogchen Ponlop, Western Buddhism is a work in progress: the teaching can be adjusted and adapted according to the conditions of the time—even the 17th Karmapa has taught a shortened ngondro practice for people with busy lives—but there are essential elements that must be preserved and clarified for the more advanced Western students.

Rebel Buddha is more than a book; it is a campaign. The campaign around the book’s publication has been fantastically planned and executed, embracing the new norms of media: blogs; Twitter; a special website; Tricycle’s choice of the book as a book club selection, with accompanying online discussion; and most impressively, the Rebel Buddha Tour. This was not your run-of-the-mill tour with the author greeting admirers and signing books. Rarely does a book on contemporary Western Buddhism get as much attention and media play as Rebel Buddha has received. Apart from the advance publicity and the well-orchestrated Internet frenzy, the tour was the main event, with stops in New York, Halifax, Toronto, Boulder, and Seattle. The Seattle iteration, to which I was party, seemed to be following a formula: guided sitting, then a short, media-savvy film on the life of Dzogchen Ponlop (featuring his “rebellious” love of Western rock-and-roll as a boy in Sikkim and his scholastic achievements), and then his perfectly timed entrance in person as the screen retracted. Dzogchen Ponlop spoke until lunch, after which there was another guided sitting, an exchange with one of his students, Tyler Dewar, and finally a panel discussion in which Ponlop was joined by Joan Sutherland Roshi, John Tarrant Roshi, and Dewar.

So who is the audience for Rebel Buddha? On the one hand, Rebel Buddha is designed to attract a “new generation” of practitioners, but on the other hand, the book is a kind of modern Buddhist version of the 12th-century Jewish philosopher Maimonides’ Guide for the Perplexed—a recognition of the need to go beyond “empty rituals and institutionalized values,” and return to direct experience without cultural filters. The “new generation” did not show up in Seattle in great numbers, however; at best, there were half a dozen people in their twenties among the few hundred in attendance. The audience was cheerful, open, responsive to jokes and questions—and as gray as the Seattle sky. I wondered, as I looked around, how the rebel theme played for them. Many of these rebels were retired and, I suspect, had given up hitchhiking long ago and moved on to the good life of Subarus and weekend cabins. Regardless, I could easily imagine that among us were covert members of the Beat Generation, a generation that Jack Kerouac described as an essentially religious one, exploring and rebelling. Surely the book’s title and subtitle, Rebel Buddha: On the Road to Freedom, were intended to evoke the alternative American dream: the nomadic Beat Generation rebels on the road, living an unconventional life of freedom. The crowd didn’t seem particularly nostalgic or rebellious, however, so I wondered what they were thinking and why they were there. The few conversations I had with audience members suggested that many of them were mature practitioners with years of diligent work behind them.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.