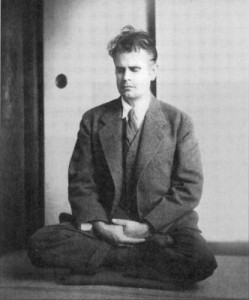

Reginald Horace Blyth was born near London in 1898, the only child of working-class parents. By the start of World War I, he was eighteen and already an eccentric in his contemporaries’ eyes: he ate no meat, loved George Bernard Shaw, and became a conscientious objector to the war, for which he was jailed. After serving a three-year sentence of hard labor and fed up with the rigidity of Britain’s class system, he left his homeland for what he thought would be a life of wandering.

But after just a year of traveling, Blyth was smitten by Asia. He settled in Korea in the mid-1920s, and began teaching English at Seoul University. He returned to England briefly to complete a B.A. in English literature in order to further his Korean teaching career. Back in Seoul, Blyth met a monk from Kyoto’s Myoshin-ji temple, the traditional headquarters of the Rinzai Zen sect in Japan. The meeting was auspicious, inspiring Blyth to take up the study of Japanese and to begin Zen practice at the Seoul branch temple; within weeks, he had moved into the temple to become the disciple of the resident Zen master, Kayama Taigi.

In 1940, Blyth moved to Japan and remained there for the rest of his life, despite being interned as an enemy alien during World War II. He married a Japanese woman and supported their two daughters working as a teacher (he even tutored the Crown Prince of Japan) and began a prolific writing and translating career. For Blyth, almost anything could be interpreted as an example of Zen, including the Western literary canon. He expounded his theories in Zen in English Literature and Oriental Classics (1942), Japanese Humor (1957), and the four-volume Haiku (1949-52), and through those books, spurring a generation of Westerners to investigate Zen and Japanese culture. Blyth died in 1964 of a brain tumor. – Eds.

I was a civilian internee from Guam, held with forty-four other men in what we called the “Marks House” (named after the former British owner) in the foreign district of Kobe, near the Tor Hotel. By the winter of 1942-43, we had been interned for one year in Japan. I was not too well, suffering periodic bouts of bronchitis and asthma, but I kept up with my reading from the library we had brought with us from our first camp in Kobe, the Seaman’s Mission on Ito Machi. I also had bought books with money supplied to us through the Swiss consul by the United States government. These books included works on haiku in English, a subject that had interested me before the war.

One evening a guard came into my room, quite drunk, waving a book in the air and saying in English, “This book, my English teacher . . .” He had been a student of R.H. Blyth at Kanazawa, and the book was Zen in English Literature and Oriental Classics, then just published. I was in bed but jumped up to look at the book and was immediately fascinated. I persuaded the guard to lend it to me, and weeks later he bought another copy for me so that he could have his own copy back.

I suppose I read the book ten or eleven times straight through. As soon as I finished it, I would start it again. I had it almost memorized and could turn immediately to any particular passage. It was my “first book,” the way Walden was the “first book” for some of my friends, the way The Kingdom of God Is Within You was the “first book” for Gandhi. Now when I look at it, even the type looks different, far smaller in size, and the references to Zen seem less profound. But it set my life on the course I still maintain, and I trace my orientation to culture – to literature, rhetoric, art, and music – to that single book.

Rinkangaku consisted of three large, connected buildings, containing dormitories, commons rooms, and classrooms. One hundred seventy-five men completely filled this complex, and Mr. Blyth lived with six others in what had apparently been the commons room for the teachers. He had his bed in the tokonoma, the alcove usually reserved for scroll and flower arrangement in Japanese homes and offices. His books teetered on shelves he himself had installed over the bed. All day long he sat on the bed, sometimes cross-legged and sometimes with his feet on the floor, writing on a lectern placed on a bedside table, with his reference books and notebooks among the bedcovers. It was during this time that he was working on his four-volume Haiku and his Senryu, as well as Buddhist Sermons from Christian Texts and other works. I recall that he wrote rapidly, with his words connected, using two sets of pen and ink, black for his text and red for his quotations.

With my interest in haiku and my new enthusiasm for Zen, we agreed that I should learn Japanese, so he obtained some elementary school texts from his Japanese wife (families were permitted a weekly visit) and gave me a couple of dictionaries. He loaned me what Zen texts he had; I remember particularly D. T. Suzuki’s Essays in Zen Buddhism: First Series in the original Luzac edition and Wong Moulam’s Sutra of Wei-lang in its original paperbound edition, from Shanghai, I believe.

I would study and read during the day while he wrote at his lectern, and in the evening I would visit his room to read my lesson to him, perhaps show him a new haiku I had written, and talk generally with him and his roommates, all of them old Japan hands, some of them partly of Japanese ancestry.

Generally, Blyth Sensei was well liked by his fellow internees, and though he was regarded as pro-Japanese by the Americans from Guam, they respected his learning and his diligence and knew that they could get straight talk from him and learn something in the process. They called him Mr. B., a nickname he rather liked. It seemed to express the balance between familiarity and formality that he sought.

If the American internees had known their Mr. B. more intimately, they would have understood that his attitude toward Japan was realistic and not blindly supportive. He had begun the process of applying for Japanese citizenship before the war, but he allowed this process to lapse after the war began, saying that if Japan lost the war, then he would renew his application. (It turned out that he died a British subject.)

“Can you imagine people like these guards occupying your country?” he once asked me. Somehow he sensed how badly the Japanese were handling their responsibilities as occupation forces in Southeast Asia, and he felt a national defeat might be the salutary experience the country would need for true maturity.

So my lessons from Blyth Sensei included political science, as well as language, literature, and religion. He seemed to regard his understanding of culture as the ground for making judgments. After the war, while teaching and in residence at the Gakushuin (the Peers School), he pointed to an encyclopedia in his bookcase and said, “I would like to make a book of commentary that would follow the main topics of the compendium of facts.”

Blyth Sensei often mentioned how as a boy he was inspired by Matthew Arnold’s ideal of developing one’s self to the fullest, to be one’s own best linguist, musician, artist, and scholar. Thus he learned Spanish in order to read Don Quixote, Italian to read Dante, German to read Goethe, and he made a valiant effort to learn Russian in order to read Dostoyevsky. And, of course, he was a deep student of Chinese, Korean, and Japanese.

As a musician, he loved the oboe particularly but played virtually all the Western orchestral instruments. While he was at the Gakushuin, he constructed an organ, a remarkable feat of technical and musical skill. His words about Bach influenced my taste during the war and directed me on the path of music appreciation I still follow. And somehow just his passing words on Turner, Sesshu, and other artists established my understanding of art.

There were flaws in this Renaissance man, however. He did not go far enough in his Zen practice to justify his confidence in commenting on the Mumonkan (The Gateless Barrier)and that book is probably the weakest of his works. He loved women and scorned them, his relations with those close to him were stormy, and his remarks about women, particularly in the essays he published after the war, infuriate readers and alienate them to this day.

I accept these flaws as I accept the flaws in my own father. The one brought me into physical being and shaped my character, the other put me in touch with myself and with this rich, wonderful world. If we had not met, I might well have spent my life mundanely, saying and doing trivial things. His words rise in my mind as I speak to my own students, and his face still appears in my dreams.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.