THE WEST TEXAS TOWN OF LUBBOCK sits in a griddle-flat territory of space and time, where paved roads at the edge of the city dissolve into wind-scorched field and dust. It’s a conservative territory of farmers and cowboys, Baptists and oil people, and it has given birth to a remarkable lineage of music writers and singers who have put Lubbock on the world’s cultural map. Buddy Holly and Waylon Jennings came from Lubbock. So did a less famous but mightily influential group called the Flatlanders, whose first—and for decades, only—recording was an obscure 1972 eight-track tape, Jimmie Dale and the Flatlanders, that turned the band into an insider’s legend. The core members of the group were Joe Ely, Butch Hancock, and Jimmie Dale Gilmore. Each went on to build intriguing solo careers: Ely made his name mostly as a rocker, and toured with The Clash for a time; Hancock is a consummate songwriter, with a sidelines in architecture and photography. After the first Flatlanders album fizzled (the result of a Nashville swindle), Gilmore didn’t make another for sixteen years. Today, though, he has seven acclaimed solo records under his belt, the latest of which, Come On Back, was the third to be nominated for a Grammy. Over the decades, the members of the Flatlanders (the name comes from a term for natives of the stark plain of the Texas panhandle) have remained friends and reunite to play, write, and record. The 1990 reissue on CD of the original 1972 sessions was aptly titled More a Legend Than a Band.

Jimmie Dale Gilmore possesses a haunting singing voice, rich and quavering, with a nasal, high-lonesome tone that gives it a lingering poignancy. And remarkably, Gilmore has staked his claim in the worlds of traditional folk and alternative country music with songs whose lyrics are the unmistakable poetry of a dharma student. On Braver Newer World, an album he made in 1996, Gilmore recorded “Outside the Lines”:

I painted myself into a corner But footprints Are just about to become part of my design Now that I’ve found myself Over the line. And I cannot blame anybody But myself Cause every single choice I ever made was mine And now I find myself A little outta line.

Whether or not Gilmore intended it to be, “Outside the Lines” is a tidy tribute to the teachings on karma and the Third Noble Truth: there is a path out. “My Mind’s Got a Mind of Its Own”—a peppy, honky-tonk number by Butch Hancock, which Gilmore recorded on his 1991 album, After Awhile, and often refers to as his “theme song”—could be taken as a paean to the struggling meditator: “My mind’s got a mind of its own/ It takes me out awalkin’ when I’d rather stay at home/ Makes me go to parties when I’d rather be alone/ Oh, my mind’s got a mind of its own.” Critics, who love easy monikers, have dubbed him the “Zen Cowboy.”

Gilmore doesn’t study Zen, and he doesn’t come from ranch people, but he is, in fact, a Buddhist. He studies under Tulku Thubten Rinpoche, a young Tibetan lama from the Nyingma lineage who now lives in Berkeley, California. But Gilmore recorded “My Mind’s Got a Mind of Its Own” long before he considered himself a Buddhist. To practitioners who are also fans of Texas roadhouse music, his songs seem like anthems to the dharma, set to music that conveys the austere, romantic spaciousness of the West.

Gilmore writes tunes that are lush and spare, all at the same time, like the songs of some of his heroes: Hank Williams, Bob Dylan, Lefty Frizzell, and the Beatles. He wrings delight out of the tension between tune and poetry, pairing, say, an uptempo Texas swing or a lilting Delta blues with a lean, philosophical set of lyrics. From his steel string acoustic guitar, he picks long, keening notes that conjure wind and space. As Gilmore sees it, music, like a religious path, is nonlinear, and songs may have a spiritual life of their own that reveals itself when the hearer is ready: “A long time ago, I wrote ‘Tonight I Think I’m Gonna Go Downtown’; it goes ‘Tonight I think I’m gonna look around/ for something I couldn’t see/ when this world was more real to me.’ To this day it expresses an image that I relate to deeply. I still open my show with it 90 percent of the time. The song doesn’t really say anything, but it expresses a feeling so perfectly. Lately, I’ve had this odd sense that I finally understand something I was saying back then.”

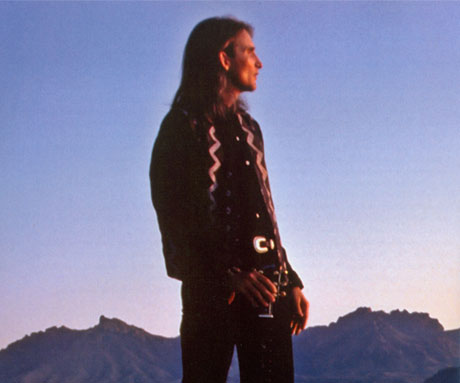

Gilmore is tall and lanky, and the leanness of his limbs and hands give his demeanor a certain delicacy. His deep-set eyes are small and almond-shaped. When something hits him as troubling or phony, they narrow and darken. His cheekbones are broad and high, and he has an elegant, aquiline nose—both features probably bequeathed by his Apache and Cherokee great-grandparents. His long silvery hair is something of a trademark—it makes him stand out in photographs and in life—and now, at sixty, he looks like a sorcerer or a shaman from some southwest version of Gondor. Like a lot of Texan men, Gilmore wears T-shirts under long-sleeved shirts, narrow-legged jeans and flat-heeled roper boots. Unlike a lot of Texan men, he drives a Prius hybrid sedan.

A Chicago music critic once deduced from Gilmore’s onstage patter that he was a man “who never met a digression he didn’t like.” Gilmore loves this description. He moves and talks in bursts of childlike excitement, cutting himself off in mid-sentence to plow into the next thought, the next anecdote, the next amazing bit of coincidence from his life. At a recent New York City gig, he admitted to hating having his feelings hurt by “stupid people.” “My policy, therefore, is to have no opinions whatsoever. Go for twenty-four hours without having an opinion—just try it,” he urged the audience. “You’ll be amazed!” He quoted Bertrand Russell on how “we cannot prove that the universe wasn’t created five minutes ago complete with memories and all. Many people find that depressing. I’m one of the ones who find it very energizing!” By way of apology for his ramble, Gilmore said, “I play this silly honky-tonk music and I think about Bertrand Russell. That’s what it’s like being inside my head.”

AS GILMORE WAS GROWING UP in Lubbock, a town with a steeple rising up from nearly every intersection, no one, amazingly, force-fed him religion. “My dad was raised in the Primitive Baptist Church and my mom in the Methodist Church. Their beliefs were fairly mainstream, but they didn’t like church. My dad promised himself that if he had children, he would never inflict it on them. He was a deeply spiritual man, but religion wasn’t discussed much.” Brian Gilmore died five years ago from Lou Gehrig’s disease and Jimmie Dale honored him with his most recent album, Come On Back, a collection of the old-timey country radio hits his father adored: “Saginaw, Michigan,” “Peace in the Valley,” “Don’t Let the Stars Get in Your Eyes.” The elder Gilmore played guitar in a country band, and named his son after the “Singing Brakeman,” Jimmie Rodgers, an icon of American country music. He took young Jimmie to his first concert, a double-bill of Johnny Cash and a baby-faced guy named Elvis Presley, and gave him his first guitar when he was sixteen. Jimmie’s first gigs were in Lubbock bootleg joints, playing solo.

Whatever subliminal spirituality may have imbued his boyhood home, Gilmore declares that his first bona fide religious influence was MAD magazine. When he was in his early teens, he would wait for each month’s issue with feverish anticipation. “I was a total MAD magazine addict. It was religious in the intensity of emotion I felt reading it, but more than that, it was the iconoclasm of the magazine, the not-taking-the-status-quo-for-granted that struck me as deeply moral. The passion for music and for MAD magazine were my first inklings of a spiritual life, that there was some internal state that was mysterious and not easy to access.” On the heels of that obsession, Gilmore became an insatiable reader of philosophy: the transcendentalists, the Beats, Aldous Huxley, Buckminster Fuller, Wittgenstein, transpersonal psychology, all poured into his head. In college at Texas Tech (where his father had run the dairy sciences department), one of Gilmore’s professors had studied under Bertrand Russell. The pieces were starting to come together. As far removed as Lubbock may have been from the centers of 1960s spiritual experimentation like San Francisco and New York, its children still caught the wave of their generation. In the early ’70s, along with thousands of other Americans, Gilmore learned about the teenage spiritual master Maharaji Prem Rawat. From the platform of his readings, he began studying meditation and Hindu Vedanta philosophy, and became such an avid disciple that Lubbock—and Texas—could no longer hold him. Not long after the Flatlanders cut that first record in Nashville, Gilmore moved to Denver to be part of a Maharaji community that had sprouted there. During the Denver years, Gilmore’s fourth child, Colin, was born to his second wife, Debby Fields. Colin is a singer and songwriter who sometimes tours with his father. (Gilmore’s three older children were born in Lubbock to his first wife, singer Carol Jo Pierce.) Gilmore remained in Colorado for nearly a decade, practicing meditation, reading fanatically, and consciously avoiding the music business; but he played and wrote songs all the while. His marriage to Debby eventually ended also, but the two remain tight friends.

Gilmore muses that during the Maharaji years, religion was “more of a hobby than a serious spiritual pursuit. The way I perceive it now, I didn’t have any real teaching; I wasn’t actually studying with a master, because I had no personal contact with Maharaji. I still have a deep love for him, but totally at a distance. I’m disaffiliated, but I’m not resentful. Far from it.” While meditation is, of course, the cornerstone of Maharaji’s teachings, there was no one to guide Gilmore across the plateaus. “I had always thought I was doing something wrong; not wrong in the sense of evil, but just incorrectly. I spent many, many, many years with a sort of low-level guilt about not meditating right. I thought that I wasn’t achieving the objective, but I didn’t realize I had barely gotten started.” In 1981, Gilmore left Denver and Maharaji and moved to Austin, Texas.

THE AUSTIN AIRPORT lets you know where you are. There’s a special section in baggage claim where guitars await their owners, and in the main terminal a giant color photograph of a nightclub stage flanked with musicians bears the caption “Sixth Street Music,” referring to the heart of the city’s live music club scene. Jimmie Dale Gilmore stands dead center in the photo with his guitar, head thrown back, his mouth shaping a vowel. In the early 1980s, when Gilmore moved there, Austin was just staking its reputation as a great music town, a generation after Willie Nelson laid the foundation. Gilmore, Joe Ely, Lyle Lovett, Tish Hinojosa, Marcia Ball, and scores of other musicians channeling the roots of country played at every local venue and justified the Chamber of Commerce’s claim that Austin was now “The Live Music Capital of the World.”

It was at one those intimate little venues where the Austin scene percolated in the eighties that another phase of Gilmore’s life began to unfurl. Up to that point, as he describes it, he’d been drinking whenever possible and practicing anything but monogamy. One night, after a gig, Gilmore met Janet Branch, a teacher from Memphis, at a table full of mutual friends. They fell in love, and have been married now for twenty years. Janet’s outward calm and elegant efficiency appear like ballast to Jimmie’s enthusiasms. In contrast to his spidery length and rapid-fire delivery, Janet is compact and graceful and speaks in a low, easy drawl. Gilmore rarely embarks on a topic without discussing Janet’s view or insight into the matter, and she was the first of the two to get serious about Buddhism.

In the comings and goings of the Lubbock crew in Austin, Janet met Joe Ely’s wife, Sharon Ely. They became good friends and began attending teachings at the Austin Shambhala Center. Jimmie would go along sometimes, but never took it to heart. He began reading more Buddhist literature, though: Nagarjuna, Shantideva, B. Allan Wallace, Robert Thurman, Joanna Macy’s Mutual Causality in Buddhism and General Systems Theory. What for years had been an intellectual interest began to coalesce. “I had a breakdown, for lack of a better word. I was reading all this stuff, and it was like my bookish spiritual understanding collided with my underlying, hypocritical hedonism. I realized that I embodied all the traits I most disliked in other people. I could see that I had always gone around with a superior attitude, that I was extremely self-centered and didn’t know it. In one sense, it was fantastic because I got the gift of the dharma. But coming to this realization wasn’t very pleasant. I wouldn’t wish it on anybody.”

IN THE WAKE of this realization, Gilmore’s meditation changed. “Over the course of a few weeks, after the sort of crashing out happened, I saw that I had always gone around with a superior attitude and I could see that it was a mask for some very deep feelings of inferiority. But rather than demoralizing me, in the context of the Buddha’s teachings, it just kindled a desire to do better, to become better. To practice being what I really wished to be. Up to that point, I had been a musician and a vagabond.” The text that acted as a lightning rod for Gilmore was a quatrain from Shantideva’s Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life:

All the joy the world contains Has come through wishing happiness for others. All the misery the world contains Has come through wanting pleasure for oneself.

“I had had spiritual experiences through my life that kept me going, but when I read Shantideva, I became a Buddhist. I finally grasped what it was I believed. The meaning of those words and how deeply I agreed with them is as close as I can get to what I think is the ultimate principle of religion. It was like the culmination of my bookish interests and my spiritual understanding. I know there’s a vast difference between reading things and actually experiencing them, but for me the experience came through the reading. Robert Thurman described that experience in one of his books; he said, ‘my rational mind was losing traction.’ The same thing happened to me as I sat reading a book.”

JANET AND JIMMIE live west of Austin in a comfortable, rambling log house in the durable landscape of Texas Hill Country, surrounded by scrub oaks, cedars, and cypress trees. Their posse of dogs, with names including Indra, Maya, and Naga, have the run of the place. In a spare, carpeted room off the living room, there’s a guest bed, a wall hung with guitars, and a tiny low table set up as Gilmore’s altar. On it sit a photo of Gilmore being draped with a white kata as he took his refuge vows, a picture of Tulku Thubten with his thousand-watt grin, and a few beloved tchotchkes. Janet’s shrine is in an outbuilding that also houses Gilmore’s music studio. Hers is bedecked with thangkas, deity statues, and a more formal altar with brass offering-bowls and incense; she calls it her “Disneyland.” Jimmie and Janet speak weekly with Tulku Thubten on the phone, and on Thursday nights they meet with their teacher’s two dozen or so other Austin-area students for chanting and meditation.

An iconoclastic kind of guy would need a teacher willing to embrace his iconoclasm. “When we met, I felt a really strong connection. I told him my history—I didn’t know if I was qualified to be a dharma student. He’s a teacher—very learned, extremely intellectual. But he’s also a spiritual friend and very open-minded. My bookishness is fine with him. In my practice with Maharaji, being a book person was not encouraged; it was even looked at as a distraction. In the dharma, the mind is regarded as one of the tools that’s used to help us go beyond the mind.” In the course of forgiving his intellect, his meditation started changing. “I began looking forward to it. If I missed a day, I didn’t feel I had committed some heinous error. The more I got into the meditation, the more my self-importance dried up.”

For his part, Tulku Thubten sees Gilmore as an untrammeled spirit who comes to the dharma with a good foundation for practice. “In our sangha, there are a few artists and musicians, including Jimmie. To my understanding, they tend to be mystical and have an inclination to transcend concepts easily. But I must say that it’s up to every individual. I have met lawyers and business people and plumbers who are very mystical, too. In Jimmie’s case, I get the impression that his heart is so open and devotional that it makes him a wonderful dharma practitioner.”

In the course of becoming a Buddhist, Gilmore says, “I realized that my personal religion, my deepest sense of what was important, has always been tied up with synchronicity and humor. When those two things are there, I sense that something’s really right.” Lately, more and more of his Lubbock cronies, the ones who make him laugh the hardest, have developed their own relationships with Tulku Thubten: Joe Ely did a Medicine Buddha empowerment with him; Sharon Ely now leads his Austin sangha; and a few months ago, Flatlander Butch Hancock and his partner Adrienne Evans took refuge and bodhisattva vows. “The three of us have always had this incredible curiosity about what we’re made of, and this drive to find out the truth, that led us into all kinds of discussions,” says Joe Ely. “What we’ve really gained from our constant quest is the fact that we can still get together and laugh, play music and it’s completely fresh: it keeps us in the present moment.” A couple of months ago, Joe, Sharon, Butch, Adrienne, and Jimmie all did a retreat with Tulku Thubten organized by Janet. Says Gilmore, “I’m coming to see my circle of friends as my guru.”

ABOUT TEN YEARS AGO Gilmore began giving songwriting workshops at the Omega Institute in upstate New York and at a kindred retreat center in the Texas Hill Country, perched on a wooded plateau not far from the Gilmore’s home, called “The Crossings.” The Crossings was conceived and built by Joyce and Ken Beck, who retired young as “Dellionaires,” the lucky folk who made a killing at Dell Computer Corporation. Their vision for the Crossings is that it be a Texas outpost for the world’s spiritual cross-currents and philosophers, a place where IT executives can meditate side by side with renunciate yogis. Gilmore has a special affection for this gorgeous, quintessentially Texan place: loping around cedar- and boulder-studded grounds, amid its swank and hushed sandstone buildings, he says he hopes The Crossings will flourish like a sort of southwest Esalen, the Big Sur retreat center at the vanguard of the human potential movement in the ’60s. Aldous Huxley may not find rebirth here, but a Jimmie Dale Gilmore songwriting retreat seems like a good latter-day substitute.

Along with Shantideva, Tulku Thubten, and meditation, the workshops have brought Gilmore to a new level of insight about his place in the universe. “For the first time ever, as a result of leading these seminars, I began to articulate ways that I had always worked and things that I had thought and felt and known intuitively, but had never put into words. I realized, first of all—and this sounds so cliche—that music is a language; one of the best; maybe the best. It has zero practical value—it doesn’t produce food, or warmth, but on the other hand, it’s as practical as anything. It’s used by churches and it’s used by military organizations. It can be used for manipulation. To this day, I’m still mystified that a song can have such a powerful impact on me. An old friend of mine from Lubbock, someone who thought I should pursue a music career, said, ‘You know, you can take the meanest, hard-headedest old cowboy you’ll ever find, and there’s at least one song that’ll bring a tear to his eye.’ I remember, as a little kid, listening to the song ‘Harbor Lights’ on the radio, when I didn’t know what a harbor was, much less had seen one. But that song took me into another world. I had a deep emotional response to it.

“Somehow, I always understood that, but didn’t put it into words until I did those classes. There’s an aspect of music that’s about pure communication. And there’s one aspect that’s so personal it doesn’t have anything to do with communication. It has to do purely with your own awareness.”

Contributing editor Mary Talbot edited “The Jhanas: Perfecting States of Concentration,” a special section in Tricycle’s Winter 2004 issue.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.