When the Venerable Tenzin Priyadarshi announced to his parents, secular Hindus, that he planned to convert to Buddhism and ordain as a monk, his father convened 76 members of his extended family to discuss the matter. Over several hours his relatives plied him with questions, an ordeal Priyadarshi calls “trial by family” in his memoir, Running Toward Mystery: The Adventure of an Unconventional Life, coauthored by Zara Houshmand. To understand his parents’ severe reaction, it helps to know that at the time of the interrogation Priyadarshi was only 10 years old. He had just run away from boarding school in West Bengal, India, and vanished without a trace. His family had spent two anguished weeks trying to locate him and finally tracked him down at a Japanese Buddhist temple in Bihar, nearly 300 kilometers from the school where he was supposed to be. At that moment, they were not feeling very sympathetic.

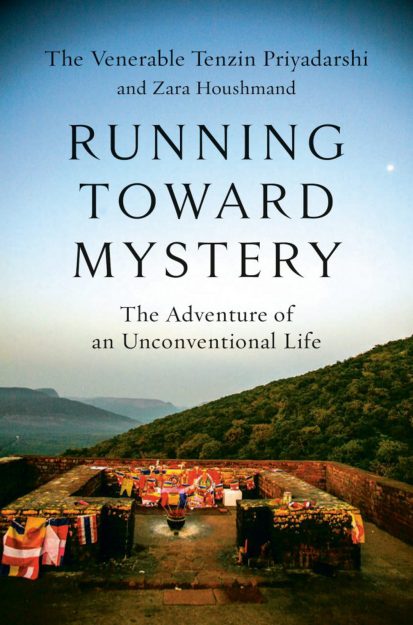

Running Toward Mystery:

The Adventure of an Unconventional Life

By Tenzin Priyadarshi and Zara Houshmand

Random House, April 2020 $28, 256 pp., cloth

The members of Priyadarshi’s clan were familiar with spiritual seekers— this was India—but these were modern, educated, and secular Brahmins. One stated flatly, “Full-time religion is what people do when they have no education, no prospects, no other way to survive.” Priyadarshi’s clan boasted prestigious scholars and prominent political leaders and social activists. They were influencers of society, not dropouts from it. “Why be a monk,” they challenged him, “when you could be respected and make a difference in the world?”

It is a fair question, one anybody might ask, even many Buddhist practitioners. Running Toward Mystery delivers one convincing answer, demonstrating the value of a renunciate life to the contemporary world. Today, Priyadarshi is a dharma teacher with an international following and serves as the first Buddhist chaplain at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). He is also the president and CEO of the Dalai Lama Center for Ethics and Transformative Values at MIT, an ethics think tank, and founding director and president of the Prajnopaya Foundation, a worldwide humanitarian organization. In 2013, the Harvard Divinity School named him a Peter J. Gomes Memorial honoree, an award for alumni who have made outstanding contributions to society. For all that, the book’s subtitle, Adventures of an Unconventional Life, refers not to Priyadarshi’s professional trajectory—his career is sidelined in the book—but to the motivations and experiences driving his contemplative life.

From the age of 6, Priyadarshi was haunted by a series of strange visions and recurring dreams. “They seemed to come from beyond me,” he writes, “beyond the world of logical sense, a genuine mystery that begged to be solved.” They beckoned him urgently, and for 4 years he resisted their siren call. But finally, in the middle of one sleepless night at boarding school, he yielded. Slipping out of his dormitory, with no money, no map, and no idea where he was going, he followed that inner compass—first by rickshaw and then by train, bus, and truck, and finally on foot—arriving two days later at the feet of his first Buddhist teacher at the Buddhist pilgrimage site of Vulture’s Peak. “I belonged here,” he writes. “I knew it with a certainty like the last piece of a puzzle clicking into place. This was where I felt complete, in a way that I had never felt anywhere else in my short life.”

His family, however, didn’t understand. “What they saw as running away, in defiance of all expectation that society had laid on me, I felt instead as running toward something that pulled me, mysteriously but irresistibly,” he writes. This was the beginning of a conflict between Priyadarshi and his parents that troubled their relationship for life. That tension frames his memoir, a story in which his parents’ conventional values and choices act as a foil for Priyadarshi’s unconventional ones.

In demonstrating the value of a renunciate life, Priyadarshi isn’t promoting the institution of monasticism. He never joined a traditional monastic community. (The monastery where he lives is within his heart and mind, he writes: “The whole world is my cloister.”) Nor is he, primarily, advocating for a traditionally Buddhist interpretation of the dharma, although he certainly does encourage that. He isn’t even lauding religion exactly. Rather he is promoting a form of contemplative life seldom addressed in contemporary biographies of Buddhist teachers written for a general Western audience—one that embraces and trusts in non-ordinary experiences, or what is usually called “mysticism.” Running Toward Mystery demonstrates the value of that form of contemplative life within the context of traditional Buddhist practice.

Priyadarshi avoids the label “mystic,” perhaps because it would exoticize his experiences, thereby countering one aim of the book. People tend to think that those with mystical ability have a special gift, but to Priyadarshi that is a wrong view. “I believe that all humans are contemplative by nature. We all share the potential for contemplative exploration that beckoned to me. Whatever we think of religion, however we are culturally shaped, we are all drawn to deeper questions about the meaning and purpose of our lives.” The mystery that beckons him is calling us too, he insists, and we could learn to embrace it. Running Toward Mystery invites us to try.

In divulging intimate details of Priyadarshi’s mystical experiences, some of which seemingly violate laws of nature, Running Toward Mystery breaks a silence about extraordinary experiences that in Western Buddhist sanghas is a dharma taboo. There are good reasons that tradition prescribes discretion: talking about unusual spiritual experiences can reify them, generate clinging, or increase pride. Yet the traditional dictate for silence exists in a context in which mystical experiences are understood as yogic; hence, they are considered unusual because they are uncommon. By contrast, framed against the backdrop of a modern Western worldview, experiences that violate the laws of nature are considered unusual because they are scientifically impossible. In that context, to not talk about extraordinary experiences is to maintain denial they can happen. So the taboo of silence, despite its merits, has a considerable drawback. It forecloses asking the important question that Running Toward Mystery implicitly raises: can modern Westerners, too, run toward mystery?

Priyadarshi clears a path of sensibility for readers to access mysticism in terms they can understand. In so doing, he makes the mystical world the baseline. As the book unfolds, Priyadarshi’s life begins to seem normal and sensible to the reader, while what starts to look strange and remote—even exotic—are ordinary ways and assumptions.

The book tells an entertaining story, but it is also full of dharma lessons. For the mystically inclined, the reading is straightforward: Priyadarshi offers insider coaching on topics like renunciation, guru devotion, and emptiness. For more mystically challenged readers like me, the narrative also becomes a doorway to examine one’s own sense of reality. It transports readers into Priyadarshi’s point of view. We come to sympathize with his perspective, and we struggle alongside him to make sense of experiences we might not consider possible. And yet those impossible experiences are undeniably happening to him and, vicariously, to us. This creates cognitive dissonance for skeptical readers and raises a provocative question: whose sense of possibility will win out? In short, as we confront Priyadarshi confronting mystery, we also confront ourselves.

A spiritual path that embraces mystery requires a very open mind. In reading this book, you’ll find out quickly whether or not you have one. Priyadarshi’s spiritual adventures run the full mystical gamut from surprising coincidences and odd familiarities to remarkable visions and downright miracles. Your first discovery, occurring perhaps in the moment a teacher steps out of Priyadarshi’s dreams and into his waking life or a deceased spiritual master appears among the living, may be the limit of your sense of possibility.

Yet it is not just Priyadarshi’s specific adventures that seem exotic. A strangeness pervades all his experiences as though embedded in the very fabric of his mysterious world, giving a through-the-looking-glass otherworldliness to the whole book. For example, spiritual practice, for Priyadarshi, is not only a moral pursuit but also an aesthetic one. The integrity that results, like mastery in artwork, is visibly evident, so he advises that students watch the teacher closely: the behavior of the teacher is “Torah to be read.” And for Priyadarshi, the uncertainty one encounters in the pursuit of mystery isn’t something to dispel; it is something to explore.The challenge isn’t to find answers but to ask better questions. “Like a prism revealing the colors contained within a beam of white light, mystery serves as a portal to deeper questions and answers than our rational minds can perceive,” he writes.

Other things also behave in unfamiliar ways. A question can “crack open the world.” A mantra contains “the whole universe imploded in a single point.” Statues and paintings open “doorways through which one could catch a glimpse of the enlightened beings they represent.” Texts provide passage to “a universe that pervaded the very air around us.” Objects are not inert here, nor are they functioning symbolically. Something uncanny is going on.

Priyadarshi has a rare talent for bridging difficult divides. He particularly shines when the communication impasse is of the most intractable sort; that is, when the differences are paradigmdeep. (It is not surprising that he has been a leader in interfaith dialogue with people like Pope John Paul II, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, and Pope Benedict XVI.) His coauthor, Zara Houshmand, has comparable talent in this respect. An Iranian American, she translates Persian literature, and as a former publications director for the Mind & Life Institute she has edited many books on the dialogue between Buddhism and science. But bridging divides between people who have different beliefs, languages, or ideas is a minor challenge compared with the more formidable task of bridging divides between people who inhabit the world so differently that they might in effect be inhabiting different worlds. Guiding a reader across that kind of abyss is the combined forte of Priyadarshi and Houshmand in this book.

They write, for example, of the night Priyadarshi cracks open a door and peers into the room where his teacher is practicing. He is stunned to see the altar on fire and his teacher sitting cross-legged amidst a blaze of light. An instant later, the fire is gone, and his teacher is sitting as though nothing unusual has happened. The next morning, the teacher acknowledges they both saw the same thing. As Priyadarshi tries to make sense of what happened, he muses:

Is it possible to contain that blaze in reason’s straitjacket? In the encounter between Buddhism and the modern world we have been quick to discard what seems alien and fanciful, and to highlight what conforms to the Western scientific worldview. . . . In all this cherry-picking we are filtering out something important. It’s not that science is wrong-headed, or that we should bend the laws of physics to accommodate the paranormal, but there is more than fits in that box. There are other ways of knowing and engaging with the world that are also valid. Deep in the heart of Buddhist philosophy at its most rational is the premise that the reality we encounter in our day-to-day lives is less solid than it appears, and that it is constructed with our participation. Science doesn’t disagree. From the ambiguities of quantum physics to the biological mechanisms of perception and embodied experience, our deepest understanding of how the world works is a lot less rigid and a lot more participatory than what hard-nosed common sense offers on the surface. And if it’s less rigid and more participatory, then it may also be malleable in ways that surprise us.

Priyadarshi calls this understanding a “less-than-solid ontology.” The word ontology is a signal that what he is questioning is the nature of being itself. Priyadarshi is targeting our felt sense of how things exist, which is something we don’t ordinarily examine. But if we don’t realize that how things exist can even be at issue—that not everyone experiences the world as solid and mind-independent—we won’t be aware that our own ontological perspective is not universal. Nor will we appreciate that there can be differences dividing people that cut world-deep.

Priyadarshi seems to suggest that whether or not Westerners too can “run toward mystery” hinges on breaking a spell—not a spell that is entrancing mystics but one that might be captivating readers. Here it helps to ask: Why might mysticism skeptics think the world is not malleable? They think the world is not malleable because they presume it is not participatory—not constructed with their participation. In fact, they likely take for granted the opposite— that the world is mind-independent. But as Priyadarshi points out, quantum physics doesn’t accept that notion, nor does Buddhism. (He cites the 7th-century Indian Buddhist philosopher Chandrakirti, “whose commentaries still serve as a classic textbook on that less-thansolid ontology.”) In a participatory world, objects function in ways that independent objects cannot. This key difference accounts for the pervasive uncanniness of Priyadarshi’s experiences and explains why what is possible for mystics may be foreclosed to mysticism skeptics.

It would have been helpful if Priyadarshi had further developed this point about ontology, because it is crucial to an understanding of the book yet easy to miss. If you do miss it, you will know you did when you reach the end of the book and wonder, as I did, why the last three chapters were included. Since these chapters aren’t about Buddhism, they seemed out of place in what I had assumed was a story about a Buddhist monk coming of age. But then I understood that these chapters show Priyadarshi stepping outside Buddhist paradigms and learning to navigate encounters with increasing degrees of difference. Two of the closing chapters show him in dialogue with representatives of other religions, Father Thomas Keating, a Trappist monk who founded the practice of Centering Prayer, and Archbishop Tutu. These chapters prepare readers for the encounter with difference that comes next.

The uncertainty one encounters in the pursuit of mystery isn’t something to dispel; it is something to explore.

The last chapter tells how Priyadarshi, in Colombia for a speaking engagement at the Universidad Del Rosario in Bogota, responds to an invitation from an isolated indigenous mountain tribe, the Arhuaco, that has been extended to him because of a 300-year-old prophecy presaging his arrival. Accompanied by the Arhuaco messengers who have traveled to Bogota to summon him, Priyadarshi flies to Valledupar, drives into the mountains, and hikes up to a sacred hilltop with a university dean and a handful of faculty members in tow. There they meet with tribal elders who deliver a message they report they have intercepted from nature itself warning of impending environmental doom. One of the elders explains to Priyadarshi that the Arhuaco see the world as one living body and themselves as the guardians of its health. The mountains are their mother, who has provided for them, so they must care for her wellbeing in return—that is their original law. “All of their understanding of nature evolved from relationship,” Priyadarshi observes. The elder was grieving because “his brothers in the outside world . . . had lost something terribly precious,” he writes. “What they had lost was the very nature of how to be human: an understanding of how to be in relationship.”

In a remarkable scene, the Arhuaco elder and Priyadarshi—neither of whom speaks the other’s language—engage in a kind of mind-meld, understanding each other “immediately and instantaneously,” well in advance of their translators. From the perspective of a modern Westerner, this degree of relational attunement seems superhuman—and hard to believe. The book implies, however, that such mastery is a possibility not magically present in a mystical world but tragically missing from a modern one.

After Priyadarshi returns from Colombia, he attends a conference on climate change and ethics at which the Dalai Lama is a participant. Priyadarshi tells the story of the Arhuaco and gives the Dalai Lama a gift from them: a piece of agave fiber adorned with a single knot. That string carries a message—“We are small threads woven together into a vast web”—and could be interpreted as a spell-breaking talisman. Faced with imminent climate catastrophe, Priyadarshi implies, modern people need to snap out of their illusion of separateness from nature and recover the lost understanding of how to be in participatory relationship with it.

Priyadarshi’s family need not have worried that his life choice would make him socially irrelevant. At this critical historical moment, if humanity is to survive and thrive, people of all cultures across the globe must find ways to recognize their commonality. “The real challenge is not the ever escalating threat of change,” Priyadarshi writes. “Change always looms, if rarely so dramatically as now. The real challenge is to bring this scattered family together to reach across the boundaries of our separate beliefs, with empathy and a shared understanding of ethics, to learn to care for one another.” In other words, Priyadarshi seems to suggest, the most pressing exigency facing humanity today is learning to navigate not change but difference. And the leaders who could best teach us how to do that might not be activists, scientists, or politicians. They just might be mystics.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.