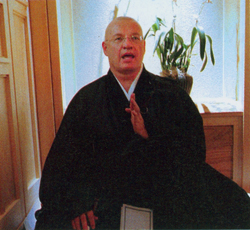

After attendees chanted the Heart Sutra to the beat of a drum, Reverend Dai En Wiley Burch of the Hollow Bones Rinzai Zen school dedicated the space with these words: “May this Buddhist sanctuary spread the dharma like a great Bodhi tree, sheltering the cadets and airmen of the United States Air Force from storms of ignorance and the suffering of war.”

Burch, a graduate of the first class of the Air Force Academy in 1959, is largely responsible for garnering the grants to help renovate the 274-square-foot hall, where the twenty-six cadets who currently practice Buddhism will finally have a decent space for their practice.

The improved dharma hall will be a bright spot for the Academy, which has taken its share of blows in the press. Scandals including lawsuits over religious discrimination, sexual assault, cheating, and drug abuse have sullied the Academy’s reputation in recent years. Most recently, questions have been raised about recruiting practices and the lack of diversity in the student body.

It is a conservative institution in a conservative city. Colorado Springs, Colorado, just an hour’s drive south of Denver along the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains, is flanked by the Air Force Academy to the north, Peterson Air Force Base and the Army’s Fort Carson to the south, with Schriever Air Force Base just ten miles east of Peterson. The city is also home to a large number of religious organizations and churches like Focus on the Family and New Life Church, founded by the recently disgraced minister Ted Haggard.

Tenzin Kacho, the first Buddhist instructor to be hired by the Academy, admitted she was initially hesitant to move to the city because “I’d heard it was a very strong conservative community, that they had a stronghold with Focus on the Family and New Life Church. But I found that the people in town were very accepting. As a Buddhist nun, I couldn’t be incognito very well.”

Buddhist faculty member and 1988 Academy graduate Dave Levy said that the Academy’s search for and eventual hiring of Kacho as sangha leader in 1999 was instigated by an encounter between the chaplain and a cadet during basic training that year, long before religious diversity at the Academy would even be called into question.

“The chaplain said, ‘OK, for Protestant services you go to the chapel. For Catholics, you go here. Jews, there’s a synagogue.’ After he finished his directions, this one cadet raised his hand and said, ‘Sir, I’m a Buddhist. Where do I go?’ The chaplain said, ‘I don’t know. We’ll find something for you.’ That initiated them finding and tracking down Tenzin.”

Of Japanese heritage and raised in Hawaii, Kacho came to Colorado in 1974 to study Tibetan Buddhism in the Gelugpa tradition in Boulder. She was ordained by the Dalai Lama in 1985 and has been a Buddhist nun for twenty-two years. Kacho, who left the cadet sangha in 2005 after being called to Los Angeles to coordinate a tour for the Dalai Lama, visited the dharma hall shortly after the dedication on October 29 and was stunned at the change. She remembered that when she had taught there, the unheated room was made of bare concrete.

“When we first started, that particular section of the chapel was so cold,” she said. “While we meditated and discussed the dharma together, we could see our breath. We’d sit with all our down coats on. Now with the dedication of the new hall, it’s one of the warmest parts of the chapel.”

With Kacho gone, there was a transition period during which a string of Buddhist teachers visited to lead occasional services and faculty members Levy and Stuart Lloyd, an assistant professor in the Department of Behavioral Sciences and Leadership, helped bridge the gap between Kacho’s resignation and the hiring of a new full-time sangha leader.

Many of the cadets who attended the dharma hall dedication said that Major Lloyd, who is currently deployed in Iraq, had influenced their decision to begin Buddhist practice because of his survey course, Psychology of Religions, which included a section in Buddhism.

Senior cadet Erin Woodside took Lloyd’s class two years ago, and it piqued her interest enough to give the weekly sangha meetings a try. Woodside, raised in a Protestant family, said that the internal aspects of Zen practice match beautifully with her Christian practice, and that the increased internal focus and quiet that sitting meditation provides have helped her through many of the rigors of life at the Academy.

“When I have a big assignment or PT [physical training] test, I stress myself out and get sick, get tired—all of these cadet-like things,” she said. “Zen says to stop and breathe. There’s a peace outside of your life.”

Leah Pound, another senior cadet who took Lloyd’s class, did not have a religious upbringing and said she came to a point in her stressful freshman year when she realized that she was suffering by not having a spiritual outlet. After she began sitting with the group, she found a sense of calm slowly creeping into her everyday life.

“I remember being at softball practice one day, and I was so mad at my coach,” she said. “Then there was just this sense of ‘Why are you mad? Do you need to be mad?’ It’s a mindfulness of noticing what I’m feeling and what I’m doing.”

Cultivating steady mindfulness, often the aim of all those hours of meditation, seems to have made its way into all of the cadets’ lives. Levy said the group didn’t do as much meditation under Kacho, but after their new sangha leader, Sarah Bender, took over in early 2006, the dynamic of the group began to change.

“It took a couple of years to get to the point where we could really consider ourselves a sangha,” Levy said. “It’s not anything against Tenzin at all. She took us from nothing to where it was when she left, and Sarah has built on that. Now it’s a community.” Levy attributed the change to the new instructor’s zest for meditation, and said the cadets had begun to take on leadership roles like timing meditation periods, striking bells, and other duties. Bender, a learning disabilities specialist with a private practice for eighteen years, began her tenure as head of the cadet sangha in February 2006. She is a sensei “fully authorized to teach Zen and work with individual students,” and this September she received her transmission from Joan Sutherland, founder of The Open Source, a collaborative network of Zen communities centered in Santa Fe with participating sanghas in California, Colorado, and Hawaii.

Bender wasted no time, beginning with basic meditation instruction and then moving on to studying the Buddhist precepts, “because the precepts are a facet of Buddhist practice in all of the Buddhist traditions that I’m aware of,” she said. “They’re guidelines that the Buddha and later followers developed for getting along with each other in the world.”

Bender listed and discussed the lay precepts against killing, stealing, indulging in sexual misconduct, lying, or taking intoxicants. “You can imagine that the discussion about not killing was pretty lively,” she said. “The cadets were aware that it was very important for them to hold that question about ‘how do we embody not killing? How do we live with the intention not to kill when we’ve taken up the form of service that we’ve taken up?’ And you heard Dai En’s take on that yesterday.”

Dai En Burch’s speech at the dedication ceremony pointed directly at the elephant in the room, the apparent conflict between Buddhist precepts and military service. “Without compassion, war is a criminal activity,” he said. “Sometimes it is necessary to take life, but we never take life for granted.”

Burch has consistently emphasized that there is no conflict between a warrior’s duties and the Buddhist life; this is perhaps not surprising, given his association with the Academy and his training in Rinzai Zen—known for the severity of its training methods and close association with samurai standards of conduct.

Bender plans to approach the dilemma from both sides. She’s already done koan work with the cadets using a book by Trevor Leggett called Samurai Zen: The Warrior Koans. “Interestingly enough, though the book is a collection of koans and is about koan study, it does discuss the context in which Zen koan use emerged in Japan, and in particular the kind of Zen inquiry that is part of the samurai training. I’ll also be going further into looking at the dark side of that allegiance,” Bender said. “It’s possible to take an emptiness perspective to an extreme in such a way as to deny the actual consequences of your actions…. There’s a book by Brian Victoria called Zen at War that really says we must look at what can happen when Buddhism is put in the service of nationalism.”

The nature of modern warfare often separates the killer from the victim, a point that cadets like Pound have obviously been mulling over. “I’m going to be a behavioral scientist. I’m not a pilot. I’m not in the fight, really. But I’ll be one of the people who design cockpits for a plane that will eventually drop bombs and kill people,” she said. “I’m trying to make this machine so efficient that a man can push a button and drop a bomb. Killing becomes easy. So that’s very closely tied to what I do. It’s kind of hard for us today, because we don’t cut across someone’s stomach with our sword and kill them; we drop bombs on them from many miles away.”

Other cadets, like senior Bradley Carroll, don’t seem to be having as much trouble. “I don’t believe there’s any conflict,” Carroll said. “I guess you can interpret the precepts many ways. I’ve chosen to interpret them in a way that allows me to continue to serve my country and do my duty.”

Bender, for her part, said she would continue to provide the tools for inquiry and for developing an openness of mind and heart, skills that would allow the cadets she works with to meet their experiences and choices fully. Her approach rejects easy answers in favor of close inquiry, good advice for Buddhist and non-Buddhist alike.

The new dharma hall is not just a bright spot for the Academy; it is a symbol of Buddhism’s growth in the United States, springing up in a place where it would hardly have been imagined only a few years before. It seems heartening that here, at a conservative American military institution, a questioning mind is being cultivated.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.