The goal of Buddhist practice, nibbana, is said to be totally uncaused, and right there is a paradox. If the goal is uncaused, how can a path of practice—which is causal by nature—bring it about? This is an ancient question. The Milinda-pañha, a set of dialogues composed near the start of the common era, reports an exchange in which King Milinda challenges a monk, Nagasena, with precisely this question. Nagasena replies with an analogy. The path of practice doesn’t cause nibbana, he says. It simply takes you there, just as a road to a mountain doesn’t cause the mountain to come into being, but simply leads you to where it is.

Nagasena’s reply, though apt, didn’t really settle the issue within the Buddhist tradition. Over the years, many schools of meditation have taught that mental fabrications simply get in the way of a goal that’s uncaused and unfabricated. Only by doing nothing at all and thus not fabricating anything in the mind, they say, will the unfabricated shine forth.

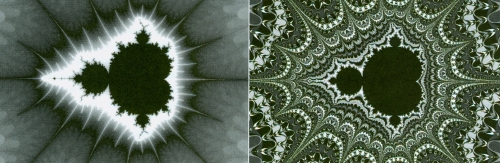

This view is based on a very simplistic understanding of fabricated reality, seeing causality as linear and totally predictable: X causes Y, which causes Z, and so on, with no effects turning around to condition their causes, and no possible way of using causality to escape from the causal network. However, one of the many things the Buddha discovered in the course of his awakening was that causality is not linear. The experience of the present is shaped both by actions in the present and by actions in the past. Actions in the present shape both the present and the future. The results of past and present actions continually interact. Thus there is always room for new input into the system, which gives scope for free will. There is also room for the many feedback loops that make experience so thoroughly complex, and that are so intriguingly described in chaos theory. Reality doesn’t resemble a simple line or circle. It’s more like the bizarre trajectories of a Mandelbrot set.

Because there are many similarities between chaos theory and Buddhist explanations of causality, it seems legitimate to explore those similarities to see what light chaos theory can throw on the issue of how a causal path of practice can lead to an uncaused goal. This is not to equate Buddhism with chaos theory, or to engage in pseudo-science. It’s simply a search for similes to clear up an apparent conflict in the Buddha’s teaching.

And it so happens that one of the discoveries of nonlinear math—the basis for chaos theory—throws light on just this issue. In the nineteenth century, the French mathematician Jules-Henri Poincare discovered that in any complex physical system, there are points he called resonances. If the forces governing the system are described as mathematical equations, the resonances are the points where the equations intersect in such a way that one of the members is divided by zero. Dividing by zero, of course, produces an undefined result, which means that if an object within the system strayed into a resonance point, it would no longer be defined by the causal network determining the system. It would be set free.

In actual practice, it’s very rare for an object to hit a resonance point. The equations describing the points immediately around a resonance tend to deflect any incoming object from entering the resonance unless the object is on a precise path to the resonance’s very heart. Still, it doesn’t take too much complexity to create resonances—Poincare discovered them while calculating the gravitational interactions among three bodies: the earth, the sun, and the moon. The more complex the system, the greater the number of resonances, and the greater the likelihood that objects will stray into them. It’s no wonder that meteors, on a large scale, and electrons, on a small scale, occasionally wander right into a resonance in a gravitational or electronic field, and thus to the freedom of total unpredictability. This is why meteors sometimes leave the solar system, and why your computer occasionally freezes for no apparent reason. It’s also why strange things could happen someday to the beating of your heart.

If we were to apply this analogy to the Buddhist path, the system we’re in is samsara, the round of rebirth. Its resonances would be what the texts called “nonfashioning,” the opening to the uncaused: nibbana. The wall of resistant forces around the resonances would correspond to pain, stress, and attachment. To allow yourself to be repelled by stress or deflected by attachment, no matter how subtle, would be like approaching a resonance but then veering off to another part of the system. But to focus directly on analyzing stress and attachment, and deconstructing their causes, would be like getting on an undeflected trajectory right into the resonance and finding total, undefined freedom.

This, of course, is simply an analogy. But it’s a fruitful one for showing that there is nothing illogical in actively mastering the processes of mental fabrication and causality for the sake of going beyond fabrication, beyond cause and effect. At the same time, it gives a hint as to why a path of total inaction would not lead to the unfabricated. If you simply sit still within the system of causality, you’ll never get near the resonances where true nonfashioning lies. You’ll keep floating around in samsara. But if you take aim at stress and clinging, and work to take them apart, you’ll be able to break through to the point where the present moment gets divided by

zero in the mind.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.