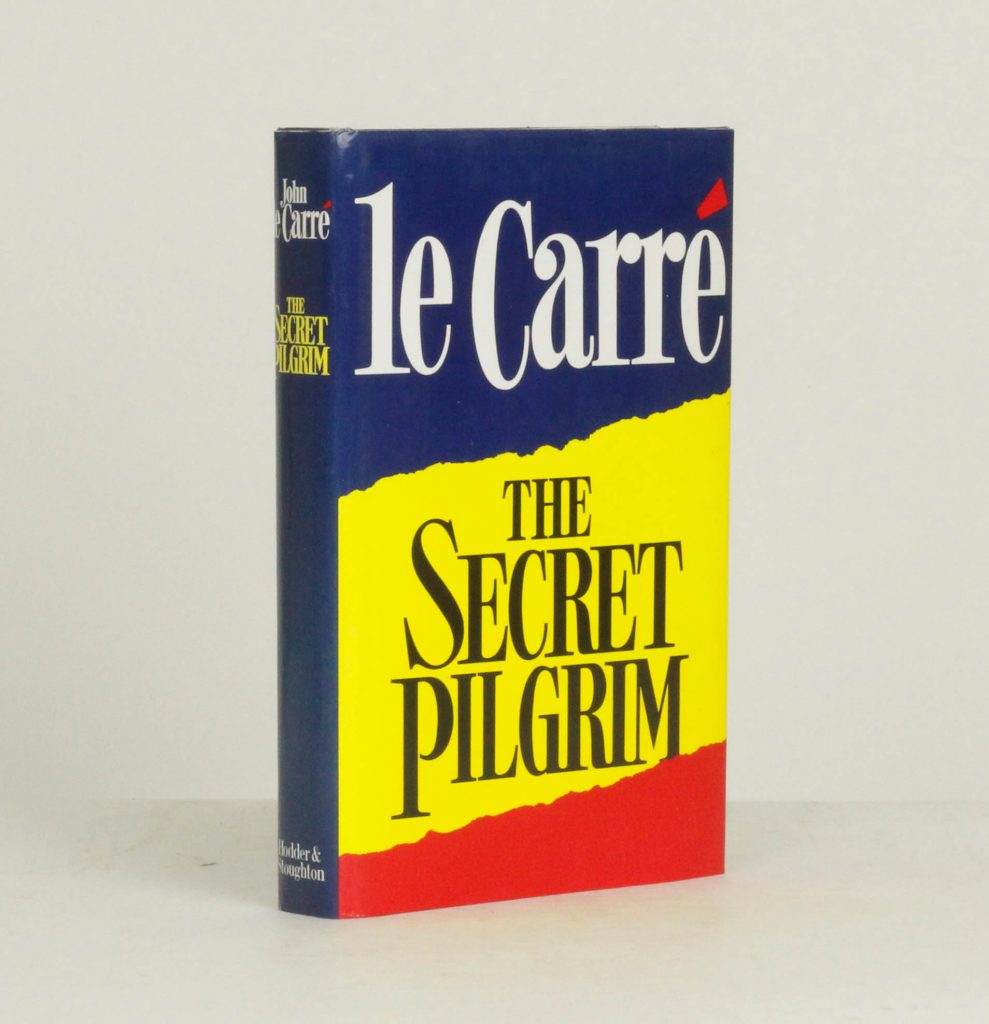

The Secret Pilgrim

By John le Carré.

Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1991,

336 pp., $21.95.

I have long been an admirer of le Carré, yet I was unprepared for his latest book, The Secret Pilgrim. And despite its great popularity I have felt alone with it, for no one I know seems to have read the same book that I did.

The Secret Pilgrim purports to be the final episode in the career of George Smiley, the inimitable and endearing ex-chief of the British Secret Service. The narrative is culled from the memory of an aging and about-to-retire training officer who has invited his old boss, Smiley, to give the “commencement” speech to his last small band of fledgling spies. The Berlin Wall has crumbled and the Cold War is over. Both le Carré and George Smiley are faced with the task of identifying the role of future spies in the west. It is no longer so clear who the enemy is. As Smiley warms to his subject, his old colleague Ned allows his mind to roam over their long years of collaboration and he starts to examine the motives that make men and women take up spying in the first place, what makes them continue, what tempts them to go over to the other side, and what, in the end, causes them to retire from the trade. As Ned’s mind throws up one vivid image after another and he recalls his involvement with people of all ages and nationalities, it gradually becomes evident that no two people—indeed no two situations—are ever completely alike and that no neat answer can be provided to any of these questions.

The reviews hailed le Carré as a master storyteller, a perceptive observer of human nature, a fine interpreter of the current political situation vis-a-vis the Soviet Union; the real subject seems to have remained completely obscured although it was there for all to see in the very title. This is not just an examination of what makes men spy but an inquiry into what makes us do anything at all—why we entered this life, what use we have made of our time here, whether it was worth it, whether we have even begun to recognize the things that are really important, and what our connection is to one another. And the key to realizing what le Carré is writing about is in Ned’s speech: “Some of us had only the haziest notion of what we’d joined. Finally we were to be enlightened.” “It is very dangerous to play with reality. Will you remember that?” “The real art lies in recognizing the truth.” “Who knows what a man hides, even from himself?” “Please don’t ever imagine you’ll be unscathed by the methods you use. There’s a price to pay, and the price does tend to be oneself.”

When I stopped to think about it, I realized that le Carré’s vocabulary has always been revealing. British spies have always belonged to “the Circus,” although I’m glad to report that in this book he advises us that it is now known as “the Service.” Then, of course, there’s the interesting phenomenon of what the spies themselves are called. Spies. Well, to spy is obviously to watch, to observe, to pay close attention, to be mindful. Spying has everything to do with seeing. And the Sanskrit term for seeing is vidya. Which also carries the meaning of knowledge, knowledge of the truth. A seer is wise beyond time and place. Even in this century and in the context of spying, we acknowledge that it is a business of “intelligence.”

In each incident in the book Ned seeks to clarify whatever it is that propels us into one action or another: “Life was to be a search, or nothing! But it was the fear that it was nothing that drove me forward. Every encounter was an encounter with myself.” “I felt a rampant incomprehension of my uselessness; a sense that, for all my striving, I had failed to come to grips with life; that in struggling to give freedom to others, I had found none for myself.” “I still looked to the world to provide me with the chance to make my contribution—and blamed it for not knowing how to use me.”

And in the end he arrives at the nub of the matter: even when the fate of empires hangs in the balance, the one thing that truly makes the difference is love. “Commitment is how I define love. Love is not separate from life. Love is totally integral to life, and what you get out of it depends on the ways and means whereby you invest your efforts and your loyalty. ” “Real love permits no rejection. There is no reward for love except the experience of loving, and nothing to be learned by it except humility.”

One more thing becomes very clear as the stories unfold: “Everything that happened to me on the way was a preparation for our meeting.” “There was no such thing to him as a casual question, let alone a casual answer.” Here is a man who realized long ago the Buddha’s teaching in the opening words of the Dhammapada: “All that we are is a result of what we have thought.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.