Abbess Fushimi was born on December 1, 1938, in Tokyo, Japan. She is the great-granddaughter of Japan’s last shogun, Yoshinobu Tokugawa. She entered Tokujo Myoin convent at the age of nine when her stepmother brought her there after the death of her father in World War II. She took the tonsure at age fourteen. Now the head abbess of Tokujo Moyin convent, she graduated from Bukkyo University, a Pure Land denominational school, in 1962.

Abbess Fushimi’s interest in photography began with her first trip abroad to India in 1966. Since the mid-eighties she has taken a thematic approach, photographing sunsets in many countries, including India, Burma, China, Cambodia, Indonesia, and Nepal. In addition to being master of the Keiho Schools of Tea Ceremony and Flower Arrangement, Abbess Fushimi is an accomplished poet and calligrapher. The following was adapted from an interview in Japanese conducted and translated by Elizabeth O’Brien.

For me, photography is a hobby. I didn’t start taking pictures as a deliberate extension of my religious practice. But I grew up in the Pure Land faith, and so I naturally approach photography with the same mind that I approach my practice. I completely lose myself in my picture taking. I achieve a state of mu, or egoless emptiness, which is the state that we must maintain if we are to reach Buddhahood. Whenever I see a sunset, whether I am photographing it or not, I always imagine the Buddha on the western horizon. That being said, I don’t find time to take many pictures at home in Japan. Photography isn’t part of my daily routine; it’s an activity I enjoy when I travel.

In my faith, we believe that all humans are inadequate beings, and we cannot possibly reach enlightenment on our own. So we throw the self away and cling to the Buddha for salvation.

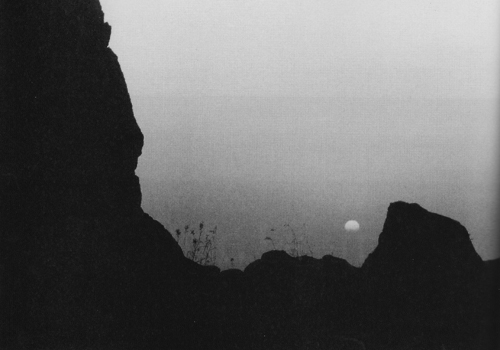

I shoot mainly landscapes, always in color. My favorite subject is the setting sun. I remember my first sunset shot very clearly. I was in southern India, and I think the year was 1984. One evening I happened upon the most glorious sunset, which I witnessed from my hotel balcony. The enormous sun setting to the west seemed to take possession of me, and I ran for my camera. Ever since then, no matter where my travels have taken me, I’ve found myself quite drawn to the setting sun. It holds great symbolic meaning in my Pure Land faith. We believe that where the sun sets is the Western Paradise, and the Amida Buddha is there, welcoming all those who have passed out of this current lifetime. We pray for rebirth in this land of enlightenment, the Pure Land heaven. When I take pictures, I am not as concerned with preserving an image as I am with capturing the fleeting moment when the sun sets and the Buddha appears in the west to greet those who are reborn in paradise.

Related: Capturing the Ephemeral

In my practice, there is no meditation per se. Our main focus is on chanting the nembutsu, “Namu Amida Butsu.” It’s an expression of oneness – the Amida Buddha and I – and a way to show gratitude for the universal compassion that the Buddha shows to all of us flawed mortals. We chant all the time, whether we’re sitting or moving, and even when we’re speaking to others we chant in our hearts.

I believe people encounter their rightful path through the workings of fate. Some people meet with an easier path, like those who practice Pure Land. Some people meet with a more difficult path, like those who practice Zen. In my faith, we believe that all humans are inadequate beings, and we cannot possibly reach enlightenment on our own. So we throw the self away and cling to the Buddha for salvation. The central force is Other-power, not Self-power. No matter how high our station in life may be, we all experience some measure of problems and earthly desires. However, in my Pure Land faith, there’s no self-conscious examination of our transgressions. We feel that we can naturally flush away these negative aspects with a sincere, continual recitation of the nembutsu. You could say that, in general, we don’t practice any kind of self-analysis.

Convent life hasn’t changed much in the last hundred years or so.

As society becomes more and more flashy and modernized, people become increasingly interested in experiencing a simpler way of living, so they come to try out life in the temple. Right away, they’re confronted with our first principle, cleaning. For most people, that means sayonara.

Not only in convents, but also in Japanese Buddhist institutions generally, there are three fundamentals: (1) cleaning, (2) religious service, and (3) learning. To tell you the truth, where I live it feels more like it’s (1) cleaning, (2) cleaning, (3) cleaning. We really put our all into cleaning. When I say “cleaning,” though, I don’t just mean physical maintenance of the garden or the buildings. It also means sweeping all the desires and the worries from our hearts. Regardless of where you are in the temple hierarchy, you have to clean. In fact, we senior members must take the lead if we expect those under us to follow.

People come to us with the misconception that all we do the whole day is sit and watch our lovely gardens grow. They don’t want to dig out weeds. They expect to come here and have their own room, with a TV, no less! They don’t want to live communally. They don’t want to deal with the temple hierarchy.

I feel that modern Japanese society is moving away from the traditional religions. Including myself, there are four women living at my convent. That being said, we don’t do too much recruiting. I’m not good at going out and speaking to large groups of people.

But I do teach flower arrangement, tea ceremony, and calligraphy to people in the local community. I have students of all ages coming to the temple to learn. Even those with no prior connections to religion come to feel the presence of the Buddha through the time they spend inside the temple grounds. I’m not looking to convert anybody. I just want to increase the number of people who pass through the temple gates, even if they only take a single step inside.

It’s very difficult to begin with students’ hearts, so I begin with the outside, teaching them the proper way to bow, the proper way to sit. I don’t speak about anything difficult; I just have them practice the proper form. And very naturally, they learn. I do consciously incorporate some religious elements into my teachings. For example, in my school of flower arrangement, we hold the five-year certification ceremony in the main hall of the temple, before an image of the Buddha. When they receive their certificates, students put their hands together and bow their heads before the Buddha. Irrespective of their religious backgrounds, the students get very excited. It’s a start. Some of my students see that as the first step and then enter the faith.

I think the master-disciple relationship is the same, regardless of the school. It’s like the relationship between a mother and a child. My own teacher passed on to the next world soon after I took the tonsure. I missed her and her guidance terribly, but thanks to the warm nurturing that I received from the other nuns, I managed to continue on my path. Now that I’ve become a spiritual mentor myself, I’ve found that the teaching works in both directions. My own disciples have taught me so much. I used to be a more impatient person, easily frustrated by what others said or did. But my students opened my mind to different perspectives. I realized that people thought about ideas that I’d never even considered before. By listening to them, I’ve grown tremendously. I think it’s the Buddha’s way of teaching me a lesson, through my disciples.

It’s outside the nature of both my personality and my faith to speak much about myself. I don’t think people are truly capable of knowing exactly who they are, and that, myself included, any attempt to define this “I” approaches arrogance. Our hearts and minds change from moment to moment, just as the clouds shift in the evening sky as the sun goes down. Who are we to think we have grasped the true nature of our souls? The Buddha-mind within us will not be constrained by the limits of language.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.