Bay Area artist Squeak Carnwath never plans a new painting in advance. Instead, she embraces the unknown, allowing the art to unfold on the canvas with each brushstroke. “I see art-making as a kind of self-making, as a way of finding out who we are, where we are, and how we’re oriented in the universe,” she said in an interview with the Oakland Museum of California. This process of discovery and rediscovery is evident in the materiality of Carnwath’s paintings, as old layers of paint and writing peek out through the new, bestowing them with a distinct illuminance.

“I see art-making as a kind of self-making, as a way of finding out who we are, where we are, and how we’re oriented in the universe.”

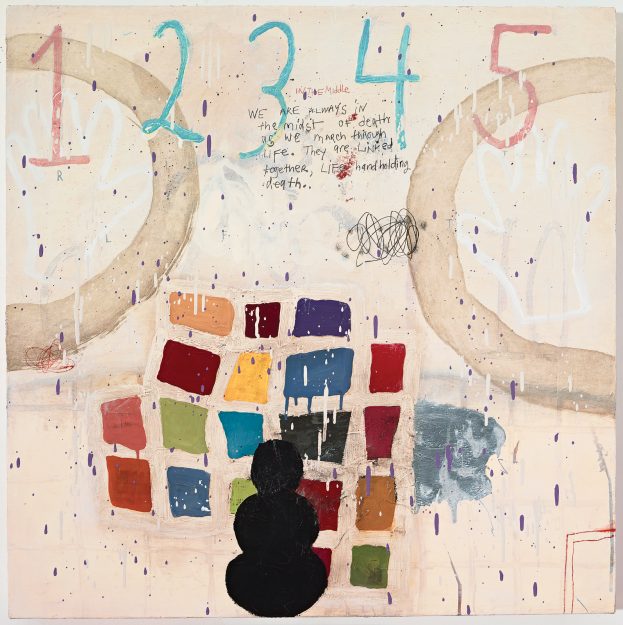

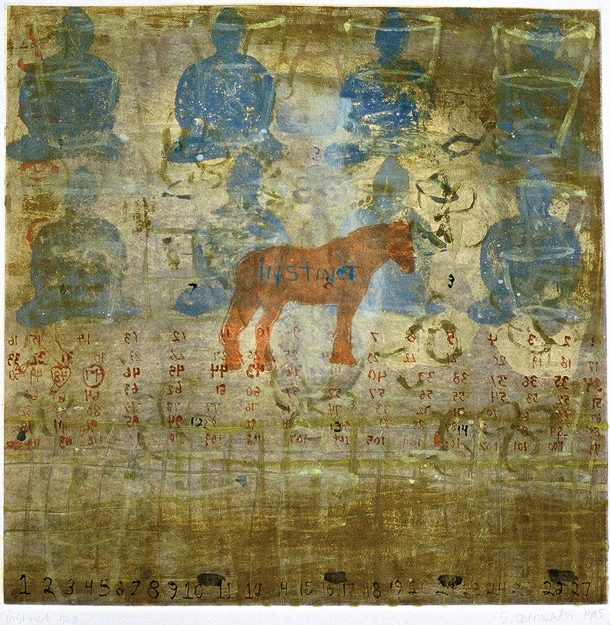

Born in Abington, Pennsylvania, in 1947, Carnwath—who goes exclusively by her childhood nickname, “Squeak”—received her MFA from the California College of the Arts in Oakland, California, in 1977, where she has lived and worked since. Though her career now spans over five decades, clear common threads connect her earliest works with more recent paintings. Carnwath’s signature blocks, dots, handprints, and animal and human figures float on top of color fields and against grids. And present in nearly every painting are lines of numbers and written observations, which she has likened to messages scrawled on the wall of a public bathroom, a space that is uniquely intimate and public.

While her repetitive use of specific iconographies suggests personal significance, Carnwath prefers to leave their interpretation to each viewer. “I like the elasticity of symbols and the fact that people read them in different ways,” she told UC Berkeley News. To Carnwath, shapes and colors hook viewers into an art object, and, after they’re drawn in, “they will start free-associating to a thing that’s familiar and can make sense of the imagery as it relates to their own life.”

How can we be happy in a world characterized by impermanence?

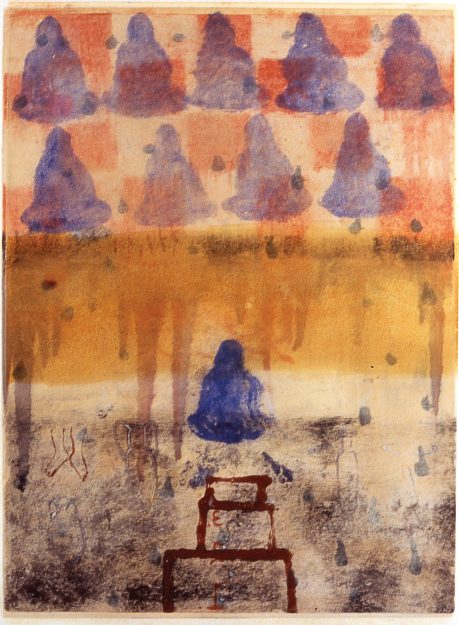

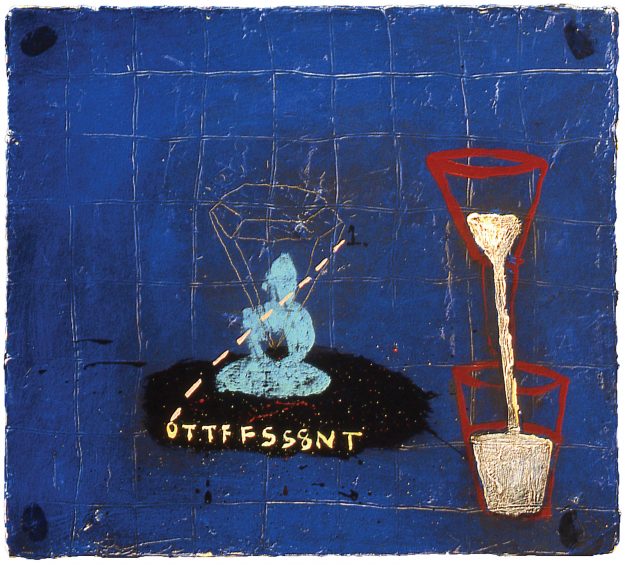

Certain symbols recall the mundanity of everyday life, such as cups of water in Instinct 1, 2, 3, while others conjure up more philosophical ideas, like the blue Buddha sitting atop a black field of stars in Buddha Funnel. In Trying Simply To Be Happy, the canvas is split into two halves, light and dark, and scrawled notes remark on the transitory nature of our world: “What are we going to do without ice at the North Pole”; and “Grafitti [sic] (from memory) as it once existed in the school elevator. It has since been sanded and ground off the steel doors.” These musings, combined with the work’s title, suggest that Carnwath is grappling with a universal question: How can we be happy in a world characterized by impermanence?

Framing all the colorful chaos and shapes are blue Buddha silhouettes, twelve at the top and twelve at the bottom, evocative of the Medicine Buddha and his twelve vows to free sentient beings from physical and mental suffering. Maybe Carnwath is suggesting that happiness is possible, that the benevolent Buddhas can guide us on a path out of the cycle of light and dark, birth and death. Or maybe it should be left up to interpretation.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.