With sixty to seventy thousand people dead and half a million more driven from their homes in barely two decades, Sri Lanka is in the grip of an epic tragedy that mocks the essential tolerance and compassion of Buddhism, the religion of the majority of the island’s people. Once a model South Asian democracy, and still the region’s most socially progressive country—with strong Buddhist, Hindu, Muslim, and Christian communities living peacefully together in many places—Sri Lanka is trapped in a suicidal civil war prolonged by politicians unable to rise above ethnic nationalisms and sheer opportunism. Both history and religion have become deadly weapons.

This war, however, is not intrinsically a Buddhist-Hindu struggle, although the Sri Lankan government, and its army, are certainly dominated by the country’s Sinhalese-Buddhist majority. They are fighting to prevent Tamil rebels from breaking off large areas of the country’s north and east as a nation for Tamils, most of whom are Hindus. Language and culture, as well as ethnicity and religion, divide them.

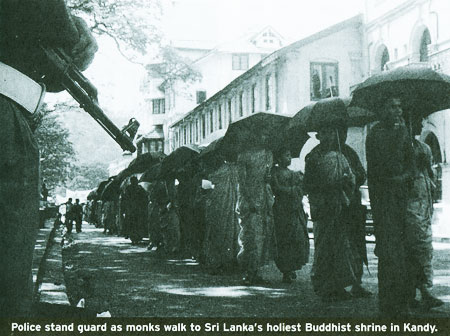

Buddhism took root in Sri Lanka more than two thousand years ago, but its early Buddhist kingdoms soon came under ruinous attack by the expansionist Hindu empires of South India. Millennia later, a suspicion of all things Indian remains part of the Sinhalese nationalist mindset—so much so that in the late 1980s, when the Indian Army came to Sri Lanka in a badly bungled attempt to disarm the Tamil rebels and enforce peace with the Sinhalese, an outburst of anti-Indian hysteria among Sinhalese nationalists fueled a second rebellion in the Sinhala heartland. Buddhist monks joined leftist Sinhalese revolutionaries in an anti-government crusade of startling brutality. That rebellion was put down a decade ago, and the rebels became a political party, the People’s Revolutionary Front. But their price for pledging recently to support a weak central government was still a promise of no concessions to the Tamils.

It is worth remembering that not all of Sri Lanka’s Tamils are fighting for Hinduism, and not all are separatists. The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (the Tamil nation), the last and most ruthless of about half a dozen Tamil rebel groups once in the fight, are, if anything, more Khmer Rouge-like in their totalitariansm, with Vellupillai Prabakharan, their leader, in the Pol Pot model. Since the late 1970s, when these Tamil groups operating from safe havens in India began to arm, saying that discrimination by Sinhalese gave them no option but separatism, fighting has centered in Sri Lanka’s north and east, where the majority of the Tamil population lives. But other Hindu Tamils working the tea plantations in the central highlands of the island have rejected separatism, as have many living in Colombo, the Sri Lankan capital, and other towns in the Sinhalese south.

Before independence in 1948, the northern Tamils, well educated by American missionaries, found good jobs in the British colonial administration. In the 1950s, the Sinhalese demanded that the Tamil presence be reduced. The “Sinhala only” language policy of President Solomon W. R. D. Bandaranaike marginalized and alienated Tamils. When I asked Bandaranaike’s daughter, President Chandrika Kumaratunga, whether she regretted this legacy, she explained that her father (who was later assassinated, ironically, by a nationalist bhikkhu) believed that the Sinhalese were in danger of losing their own cultural roots.

Can there be peace? Over the last year, Norway tried to broker talks, but progress has been elusive because of President Kumaratunga’s political vulnerability and the consequent inability of the political opposition to put national interests above the lust for electoral advantage.

Throughout the war, which has been fought mostly in skirmishes, ambushes, and acts of terrorism, there have been no significant peace movements led by Hindu or Buddhist leaders, despite the nonmilitaristic ideals of both religions. Only within the last few years has a movement struggled to arise despite government restrictions on demonstrations. The Sri Lankan Sarvodaya movement, known primarily for village development, was begun by Buddhist A. T. Ariyaratne, a former teacher. The movement is essentially Gandhian— nonviolent but more ecumenical than religious in inspiration. Sarvodaya calls repeatedly for cease-fires, saying that a generation is growing up knowing nothing but war. “We treat our children as cannon fodder for ethnic nationalism,” Dr. Vinya Ariyaratne, executive director of the movement, said recently in an interview. But Sarvodaya’s success, and that of a newer movement organized by business leaders, has been small, and the carnage continues.

A few iconoclastic scholars of Sri Lankan Buddhism, foremost among them H. L. Seneviratne, a Sri Lankan-born professor of anthropology at the University of Virginia, argue that mass Buddhism on the island has sunk to self-serving ritual bereft of the reason, generosity, and goodwill needed to override ethnic boundaries. “Forgetting the universalism of Buddhism, Sri Lankan Buddhists remain tethered to parochialisms of caste, kinship, neighborhood, race, color, language, ethnicity, and so on,” says Seneviratne, author of The Work of Kings, an examination of Buddhism’s evolution in Sri Lanka.

“Why is there no peace movement or anti-war campaign in Sri Lanka?” Seneviratne asks. “The answer is perhaps contained in the striking fact that most Sri Lankans themselves never ask the question.” ▼

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.