I noticed the afternoon was getting hotter as I unloaded my family from the car at the Subang Jaya Buddha Vihara in a suburb of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. “It’s going to be great,” I convincingly reassured my two kids. “How often do you get to see someone ordain for real?” We had come to witness Chin Leag’s pabbajja, or ordination as a novice monk.

I first knew Chin Leag in March 1998 through chatting on the Dhamma-List, a locally hosted Internet mailing list. He was an anonymous voice, appearing as words on a computer screen. I had pictured him to be in his mid-thirties. It was several weeks after we knew about each other that we met in person. One Sunday morning at the Brickfields Vihara, I overheard a pale, young man talking to a friend about a comment someone had posted on the List. “Hey, that was me. I wrote that!” I remarked to the stranger. His astonished look mirrored my own. That was how we met, almost a year ago. Six months after that, he posted a cryptic message to the List saying, “I got the permission.” That was his first announcement of his intention to go forth. He was twenty-seven years old. It was not all smooth sailing.

I wanted very much to have my children attend an ordination service. My son, aged eleven, and daughter, seven, attend the local Sunday Dhamma school, so taking them to a vihara would not be strange. The sight of images and monks is not new to them. Indeed, they are right at home running around the shrine and playing their children’s games. For several years, it has been a part of our life to visit the various viharas in the city for talks, community events, and such, but the ordination of a monk is an extremely rare event. So I had expected them to be as excited as I.

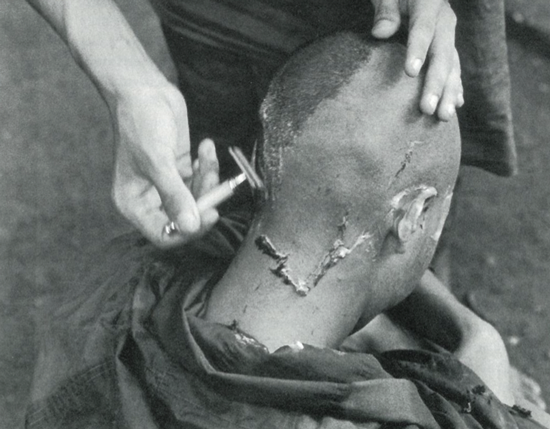

When we arrived, several people, mostly in their twenties, were already at the vihara. I assumed they were mostly members of the vihara’s youth group. Lots of chattering, giggling, and noise. I met up with some of the other Dhamma-List members from various Buddhist societies. It was like family—one of our own is ordaining. Someone popped his head through the door and said that the ordination would be held upstairs in the Sima Hall. So we all trooped up the stairs. Chin Leag’s parents, brother, and sister were there. A stool was arranged in the corridor for him to sit on for the hair-cutting ceremony. Then, one by one, his friends stepped up to snip off his hair. It started solemnly enough, but it had to come—comments on his new punk hairstyle. After the scissors had passed through the hands of about thirty people, Chin Leag’s head was beginning to look like a scalded cat. More chattering, giggling, and noise. Less than one hundred meters away, cars caught in the Kesas Highway jam were honking. This was not turning out to be the awe-inspiring event I had expected. I tried to visually transpose the scene against the Ganges Valley of the Buddha’s time but did not achieve much success. So I observed the father, who was grinning, looking very much like a bride’s father at his daughter’s wedding. The mother, however, was a silent spectator, alone with her thoughts.

When Chin Leag’s hair was sufficiently depleted, a monk told us to gather in the Sima Hall while the novice-to-be shaved off the rest of his ashubha hair. (Maybe I was just trying to be humorous thinking of it that way, because in Pali, ashubha means “foul,” and in Theravada ordinations the novice is supposed to reflect on the foul bits and pieces of the human body as his hair is shaved off.)

So we all went in and waited. And waited. The abbot who officiated at the ceremony sat motionless at the front. No more chattering and giggling. Things were beginning to get serious. But we waited. My kids started a boxing match in the Sima. A thought arose: “Opportunity for practicing patience,” but I chose not to follow through. So I growled at them, then I got up to see the action outside. I walked over to the lavatory where I knew Chin Leag was and peeked through the open door. There he was, standing in front of the mirror and turning his shaven head from side to side, examining it. It reminded me of a girl putting on lipstick. Then he was putting on his robes, so I tiptoed back to the hall.

In a few minutes, the brown-robed Chin Leag shuffled in and took his place in front of the monk. The abbot opened up a book and started reciting the formula for the Taking of Refuge and the administering of the precepts. Chin Leag followed hesitantly. There was some confusion somewhere along the process. “Wow, no rehearsal,” I thought. In less than ten minutes the ceremony was over, and Chin Leag was bestowed the name Samanera Kumara. (Samanera is Pali for a novice monk who takes the ten precepts.) There were smiles and agreeable nods all round. People started to dig around for their ang-pows, small red packets holding money that are given out on auspicious occasions, following Chinese custom. Then the abbot picked up a book from his side, flipped to some pages, and started to read theSekhiya (rules of etiquette for monks). “Rule number one: I will wear the lower robe wrapped around me, a training to be observed. This rule means that the novice must wear the lower robes in public. Rule number two: I will wear the upper robe wrapped around me, a training to be observed. That means the novice must wear the upper robe also. Rule number three: I will go well covered in inhabited areas, a training to be observed. This means . . .” After a few more rules, his voice began to fade as my head started to nod into sleep. It wouldn’t be so bad if I could understand him. Because the congregation was largely Chinese Malaysian, the abbot, who was Burmese, was trying to speak in English, and he struggled to explain each and every rule slowly and carefully. The ceremony continued. “Rule number twenty-four: I will not sit with my head covered in inhabited areas, a training to be observed.” I tried to pick up his words. “Rule number twenty-five: I will not go tiptoeing or walking just on the heels in inhabited areas, a training to be observed”.

My attention wandered off across the room. Most of the people were hunched over, staring down at their feet. I was feeling sorry I convinced my wife and kids to come. I had assured them it would be more interesting than shopping at Carrefour, a nearby mall. I looked at them. They were staring at their feet.

I looked at Chin Leag’s mother again. She had hardly spoken a word throughout the proceedings. Now she was sitting, leaning back against the wall, her eyes fixed on her son’s crisp brown robes. Chin Leag had told me she was very resistant to his ordination. I wondered what she was thinking then. What goes on in the mind of a mother who had carried her baby, cuddled him, fed him, raised him to an adult, cried over him, dreamed big dreams for him, and then seen him turn away from it all? I felt sorry for her. If mothers cry at their daughters’ weddings, a son’s ordination must be even more heartrending. Gone are her dreams of a doctor or lawyer for a son. Gone are her dreams, all wrapped up in brown, to be sent away. I noticed their eyes did not meet. Mother and son, two dreams in opposite directions.

Chin Leag had told us that when his grandmother heard of his decision, she called him over the phone and cried bitterly. He was her favorite grandson. Why was he doing this? Why now, after a full university education? On the Dhamma-List, he asked for help. How do you explain to others and to your granny that you want to become a monk? Suggestions came in from different parts of the world. Be honest, some said. Explain the Dhamma to her, others suggested. I contributed my own philosophical piece. In the end, he told us he was going to visit his granny just before the event to say the same words he had said to his mother to obtain her permission. He would explain that he had to follow his heart. And that if he didn’t, he would regret it for the rest of his life, not knowing where this path would have taken him; not knowing the wonders and opportunities he would miss. He had been given this chance for the highest quest and he could not let it slip by. Chin Leag did not tell us what his granny’s reaction was. When he was back on the List, he did not relate the event but spoke only about Dhamma, just like on any other day.

“Rule number twenty-six: I will not sit holding up the knees in inhabited areas, a training to be observed,” the head monk droned on. I glanced at him, then back at Samanera Kumara, my friend. Yes, he had heard the sound of distant drums. Many of us have heard them in our past, too. Most of us simply chose to ignore them and get on with our busy lives. We may also choose to blame our conditioning, or say that it was the wishes of our parents, or expectations of society. Whatever it was, we made the choice to close our ears and turn away. So the drums remained as echoes in the back of our memories. But Samanera Kumara had turned toward their sound.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.