From sheltered youth to forced laborer to government official, Arjia Rinpoche tells the story of his extraordinary life in Chinese-occupied Tibet, including an eyewitness account of one of the most infamous events in recent Tibetan history.

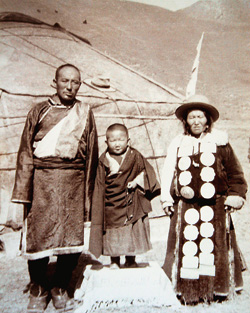

Arjia Rinpoche was born in 1950, the same year Mao Zedong’s People’s Liberation Army invaded Tibet. His early years were ones of geographical and political isolation. His nomadic family herded their yaks across the high plains of the Tibetan-Mongolian border, their camp never far from the vast blue waters of Lake Kokonor. At the age of two, he was recognized by the Tenth Panchen Lama (the second-ranking figure in Tibet after the Dalai Lama) as the reincarnation of the father of Tsongkhapa (the founder of the Gelug sect of Tibetan Buddhism). At the age of seven, he was sent to live in Kumbum Monastery, one of Tibet’s six great monastic universities.

In the following years, the Arjia Rinpoche’s life became a series of extreme swings of fortune: first as a carefree child, then as a protected and revered incarnate lama, then as a youth singled out and ridiculed by the Communists, then as a forced laborer in a Chinese camp, then as a “rehabilitated counterinsurgent” released from hard labor at the age of thirty, and, finally, as a favorite of the Beijing hierarchy, he was named head abbot of Kumbum Monastery, a position that proved to be more political than religious; it paved the way for even higher positions, including vice-chairman of the Chinese Youth Association, vice president of the Central Government’s Buddhist Association, and member of Beijing’s Central Government.

Arjia Rinpoche also remained closely aligned with the Tenth Panchen Lama throughout this time. He acted as his assistant for many years and was with him the day before he died in 1989—an event still shrouded in rumors of foul play. After the Panchen Lama’s passing, Arjia was named a member of the Communists’ nominating committee, created to select a new Panchen Lama, a task traditionally left to the standing Dalai Lama. He witnessed firsthand as the Communists choreographed the “lottery” for the Eleventh Panchen Lama. (The little boy who had been the Dalai Lama’s choice was apprehended by the Chinese; tragically, the boy’s whereabouts are still unknown.) After the rigged selection, Arjia Rinpoche was named tutor of the new Panchen Lama. Demoralized and realizing that he could no longer support the grim charade of a false Panchen Lama, Arjia Rinpoche fled China. Against tremendous odds he successfully eluded the Chinese and in 1998 reached American soil, where he was granted political asylum by the United States Government. His escape remains a major source of embarrassment for China’s Central Government.

In 2005, the Dalai Lama appointed Arjia Rinpoche the director of the Tibetan Cultural Center (TCC), in Bloomington, Indiana. His Holiness’s eldest brother, Professor Thubten Jigme Norbu, established the strictly nonpolitical, nonprofit TCC in 1979 to support Tibetans both in Tibet and in exile and to preserve Tibetan (and Mongolian) Buddhist culture. This past March, I interviewed Arjia Rinpoche at his office in Bloomington.

—Mikel Dunham

Rinpoche, one of the fascinating aspects of your tumultuous life is the extent to which you were insulated from the Communists up until the very day that they seized control of your monastery, Kumbum. You were eight years old at the time. Would you recount that day? It was in 1958, the beginning of Mao’s Great Leap Forward and a year before the Dalai Lama fled Tibet. Freedom to practice Buddhism was deteriorating rapidly, but I had no idea. The cadres who were stationed at Kumbum Monastery had been forcing all the monks at Kumbum to attend political sessions for months on end. But I guess because I was so young, I wasn’t required to attend. The monks, particularly the monks in their teens and early twenties, were being successfully brainwashed by the Communists and trained to speak out against religion, landowners, reincarnates, teachers, and so on.

One day that winter, the cadres called the entire monastic community to an outside meeting in Kumbum’s central square. There were somewhere between thirty-five hundred and four thousand of us. Soldiers with guns surrounded the courtyard and lined the rooftops, their machine guns trained on us.

Some of the monks who had been drilled by the Communists began to shout slogans at the rest of us: “Time for revenge!” “Time to uncover the wrongs of religion!” It was the first time that I had witnessed thamzing—a Chinese “struggle session” [public trial]. The police grabbed a few of the most important lamas, including the head abbot of Kumbum, who was in his early sixties. They tied his hands behind his back with rope, very tightly. He cried out. Young monks yanked him by the rope and pulled him toward the bottom step of the high stage so that everyone could see him. They yelled, “You are sucking our blood! You are eating our flesh!” The abbot was sobbing. He was the first one at Kumbum to be treated like that.

In all, over five hundred monks and lamas were arrested, beaten, and dragged away that day. My tutor, my housekeeper, my assistants—all of them were pulled away from me where I was sitting. The only rinpoches who were not arrested were the very young boys like me—ages six to ten, something like that.

The meeting lasted until late in the afternoon. I was paralyzed. I had no idea what to do. I didn’t even know where I was supposed to go. It was the first time in my life that I had no adults to take care of me. The only thing I could think to do was to go back to my rooms. But when I got there, young monks had been moved into my space. My residence had been reorganized into a commune: Team Number One, it was called.

In the following weeks, we were forced to cut up our maroon robes, dye them black or dark blue, and refashion them into Mao suits. Those became our new uniforms. We had mandatory study groups every day, endless: the cadres taught us why religion was so bad, and why religious reform was so necessary, and why the most venerated lamas were the ones who most deserved thamzing. Basically, Kumbum became a school where children were taught to denounce monasteries and the elder lamas who ran them.

The following March, in 1959, His Holiness the Dalai Lama fled Tibet, leaving the Panchen Lama the most powerful religious figure in Tibet. What was your connection with the Panchen Lama? There was a family connection. The Panchen Lama’s tutor, Gyayak Rinpoche, was my uncle. Also, we all came from the same area in Amdo province. And historically, all the Panchen Lamas had been closely aligned to Kumbum Monastery, so there was that as well. It was the Panchen Lama who identified me as the reincarnation of Lama Tsongkhapa’s father when I was two years old. The Panchen Lama was only fourteen at the time. Then, in the early 1960s, he passed through Kumbum and made arrangements for me and another young monk to be transferred to Tashilunpo—the official seat of the Panchen Lama, in Central Tibet [Shigatse]—so that we boys could study the sutras without so many cadres watching us.

Some historians have portrayed the Tenth Panchen Lama as little more than a Communist puppet—a stooge for Party rhetoric and propaganda. Not at all. After the Dalai Lama fled to India, the Panchen Lama became the number one protector of Buddhism inside Tibet. In spite of the difficulties presented by the Communists, he stood up, spoke out, and did his best. He traveled tirelessly and investigated many places to see firsthand what was happening to his people and their monasteries. He complained to Beijing: “You said that communism would be good for us, but you are doing bad things in my country.” In 1962, he met with Zhou Enlai, the premier of the People’s Republic of China [PRC], to discuss a very critical petition he wrote about the worsening situation in Tibet. And eventually, of course, he got into serious trouble with the Central Government for being so confrontational, particularly after the onset of the Cultural Revolution. He was thrown in jail in 1968.

You didn’t escape the hardships of the Cultural Revolution either. No, I didn’t. I was singled out because I was a recognized reincarnation. Apart from the mental abuse, I was also sentenced to hard labor, from the time I was fourteen until I reached thirty; fieldwork in the summertime—plowing, planting, hoeing, harvesting, animal husbandry—and the rest of the year I was sent out to work on the construction of dams or roads. Sixteen years I worked like that, until about 1980.

From sheltered youth to forced laborer to government official, Arjia Rinpoche tells the story of his extraordinary life in Chinese-occupied Tibet, including an eyewitness account of one of the most infamous events in recent Tibetan history.

Why so long? The Panchen Lama got out of prison in 1977. Well, yes, he was released from prison after Mao’s death in 1976, but he remained under house arrest in Beijing until 1982, when the PRC authorities pronounced him “politically rehabilitated.”

When were you pronounced “politically rehabilitated”? Two years before the Panchen Lama, actually. Kumbum Monastery was reopened. Monks could return to practice there, including my uncle, Gyayak Rinpoche—although he was held under house arrest at Kumbum. Whenever my uncle and the Panchen Lama needed to privately communicate with one other, I acted as their go-between. I traveled back and forth from Kumbum to Beijing to relay their messages. That was when I really gained the Panchen Lama’s trust, even though I was fourteen years his junior. Then, after he was “rehabilitated,” he quickly rose to important positions, including vice-chairman of the National People’s Congress. This allowed him an enormous amount of freedom, including trips abroad, which was quite unusual in those days. Often I went with him as his assistant: Nepal, Canada, Brazil, Bolivia, Uruguay, Peru, and other South American countries.

You also helped him establish his private company, Kanchen, which among other things oversaw the building of the only hotel in Beijing catering to nomads. What was that all about? The Panchen Lama wanted to establish an office separate from the Central Government. He wanted complete control of his activities. In order to do that, he had to be financially independent—thus his construction of the Tsongtsen Hotel in Beijing and other enterprises. Kanchen was quite successful. Kanchen means “the treasure of the snow lion.” He created branches in different provinces. His idea was to supply all necessary funds for Buddhist projects without the Chinese authorities constantly breathing down his neck. Financially, the government would not have to worry, so his association with the Buddhist monasteries in Tibet became a more independent affair. It was a brilliant plan. Throughout the eighties, until his passing, the Panchen Lama was able to acquire significant funds for the monasteries. He was responsible for retrieving countless sutras and statues and sacred objects—all taken away from the monasteries during the Cultural Revolution. Those that hadn’t been destroyed, he would track down and persuade the Communist leaders to “make gifts” to the monasteries, which was just a nice way of saying return property to the monasteries.

Party leaders were never jealous or suspicious of his independence? Well . . . there was always a lot of pulling and pushing—positioning of power, that sort of thing.

But the Chinese never openly objected to the privileges his independence afforded him? Not in so many words, no. Of course later, after the Panchen Lama’s passing, there was the rumor that he had died of poisoning. That was never medically proven. But if the rumor was true, I think the most likely reason for his poisoning would have been his establishment of Kanchen, and the independence his company gave him from the Central Government.

In your forthcoming autobiography, you write about the difficulties the Panchen Lama faced in Lhasa in the autumn of 1987. A few monks from Drepung Monastery came into the Barkhor District [the old part of Lhasa] and shouted the two treasonous words “Free Tibet.” Four days later, several hundred monks from Sera Monastery marched on Barkhor, and all hell broke loose. The Chinese opened fire. Lhasa became a battleground. Beijing sent the Panchen Lama to Lhasa to assess and quell the situation. And you went with him. The mood was very ugly. The Panchen Lama headed up three teams flown out to Lhasa in a private jet. There were about one hundred of us: the religious team, which was the Panchen Lama’s hand-picked group; the political team, which was composed of Communist cadres; and the police. You can imagine the tension in the airplane. There was the unspoken understanding that if the Panchen Lama couldn’t clean up the mess, more drastic measures would be taken by the Central Government.

The TAR [Tibet Autonomous Region] cadres arranged for a viewing at the Panchen Lama’s residence of videotapes taken during the demonstrations that would prove the Chinese were blameless. There was lots of footage of the monks shouting and demonstrating in the streets, but no coverage at all of how exactly the police were handling the Tibetans. When it was over, the lights came on and the Panchen Lama looked around the room. He said, “That’s it? That’s all? Where are the police in all this?”

And then he got really mad. You should understand that the Panchen Lama could be very imposing when it suited him. He cast a big shadow. So he walked over to the guy who was operating the video and grabbed him by the collar and yanked him up to his feet and yelled at him.

It must have been about midnight. The Panchen Lama said, “Okay, let’s go!” and herded us out to the cars waiting outside. “Get into the cars!” he ordered. “All of you!” Off we went to TAR Headquarters—just five or ten minutes away—which was also the private residence of the TAR Party Chief, Hu Jintao [currently the Paramount Leader of the PRC].

The Panchen Lama knocked on Hu Jintao’s front door. All of us Tibetans were a little proud. It was such an unusual feeling to watch a high-ranking member of the Party being bullied by a Tibetan! Hu actually came to the door in his pajamas. Personally, the Panchen Lama and Hu were friends at that time, so when Hu saw him, he called him “Great Master” or something like that and was very shocked and asked what in the world had happened.

The Panchen Lama said, “Do you trust me or not? If you don’t trust me, I can go back to Beijing. I can leave tonight! You don’t want me to investigate, then you report back to the Central Government!” The Panchen Lama—I’ve never seen someone so brave. The next thing I knew, everybody was making phone calls. The Panchen Lama was calling Beijing. Hu Jintao was calling his police. A little later, a Chinese guy came to Hu’s residence and produced a tape and gave it to the Panchen Lama. This version was entirely different. This time, we could see Chinese police all along the rooftop of the Jokhang, the holiest temple in Tibet. Then the monks came crowding down the street. The police started yelling very bad things down at the monks, and then we saw the police open fire on the monks.

The Panchen Lama confronted the police, “Why would you start shooting the people? You are supposed to represent and protect the people.” The Panchen Lama could be fearless.

Many contend that he paid for his fearlessness with his death. You were with him in 1989 in Tashilunpo, the day before he died. Can you explain why so many lamas had come to Tashilunpo at that time, and why the rumors of murder won’t go away? Traditionally, the final resting place of the relics of the previous Panchen Lamas was Tashilunpo. Prior to the Cultural Revolution, each Panchen Lama had his own memorial temple. During the Cultural Revolution, most of the relics were taken and the temples were destroyed. But after 1980, people began to secretly approach the Tenth Panchen Lama with bits and pieces of the relics. Eventually, he collected the relics of five of the previous Panchen Lamas. So he built a temple with a central stupa and, within this stupa, he put five safes to house the relics. The opening ceremony for this stupa—a two-week affair—was the reason for the Panchen Lama’s last visit to Tashilunpo. This was in December 1989. Almost all the high lamas of Tibet were in attendance. Naturally, his unexpected death was a major shock to everyone.

But there were also political overtones to the celebrations, right? That’s true. At one point the Panchen Lama gave a long speech, and much of it was critical of the Chinese government. It was a political speech. But it was given in the context of recent history. In other words, he recounted many bad things that happened during the Cultural Revolution and then cautioned the Chinese government to take heed of its own mistakes and to avoid them in the future. As always, he had to be careful when he did this.

People have accused the Chinese of killing the Panchen Lama because of that particular speech, but I don’t think that’s logical. They kill him because of one speech? I don’t think so. For one thing, anytime the Panchen Lama was scheduled to give a public message, he had to submit a draft of his speech to be approved by the Chinese censors, so really, that one speech could not have come as a big surprise. Anyway, the celebration lasted for two weeks. The night before everyone returned to their own monasteries, we had a big party. Everyone was so happy! And then we left. My group was returning overland to Kumbum. We had just arrived at a place north of Lhasa when we heard a radio broadcast that announced the unexpected passing of the Panchen Lama. We were stunned. Speechless. Every Tibetan felt torn apart, and suspicious.

What was the official reason for the Panchen Lama’s death? High blood pressure. It’s a plausible explanation. He was considerably overweight. I would be surprised if he didn’t have high blood pressure.

But your uncle, Gyayak Rinpoche, remained in Tashilunpo with the Panchen Lama after you left. What did he say about the Panchen Lama’s death? I was told that after the big party, the Panchen Lama complained that he was feeling uncomfortable. A doctor came in and gave him a pill and that was it. The next morning, early in the morning, they discovered him in his room and he had passed away, apparently in his sleep.

But there is something very interesting beyond that. Gyayak Rinpoche’s assistant told me that when they visited his body that morning, the Panchen Lama’s face was very calm and beautiful. They began doing prayers for him. But when the Chinese found out, they brought in guys who tried to resuscitate the dead body nearly all day! Until four o’clock in the afternoon! They just would not leave his body alone. Why would they do that? Is that not a little strange? From seven a.m. to four p.m.—nine hours of resuscitation?

And was Hu Jintao still the Party Chief of the TAR at the time of the Panchen Lama’s death? Yes.

From sheltered youth to forced laborer to government official, Arjia Rinpoche tells the story of his extraordinary life in Chinese-occupied Tibet, including an eyewitness account of one of the most infamous events in recent Tibetan history.

And rumors arose connecting him somehow. Yes, but people soon turned their attention to choosing the next Panchen Lama, the Eleventh. That became the most important thing.

The selection didn’t occur until 1995—almost six years after the Tenth Panchen Lama’s passing. Why the long gap? From the very beginning of the process, there were so many obstacles created by the Chinese government. Number one: they made it quite clear that they intended to be part of the election process. In the first stages, they seemed open to speaking to the Dalai Lama. They formed two teams: the political and the religious team. I was appointed secretary of the Religious Selection Committee. But there was also the problem with the Tibetan community.

Before I go on, I think I should mention something about the character of the Tibetan people in general. They have a kind of weakness when it comes to harmony with one another. Our mind process is like this: I’m from Amdo, you’re from U-Tsang, he’s from Khampa; we are all different—separate. Tibetans don’t really think of themselves as one big family. So right from the beginning, there were regional rivalries that played into the selection of candidates for the Eleventh Panchen Lama. First of all, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama and the Tenth Panchen Lama were both from Amdo. So some of the people said, “This time, the Panchen Lama should come from Lhasa, not Amdo.” The general feeling among the Tibetan team was not one of compromise. To make matters worse, Gyayak Rinpoche, who was initially head of the religious team and a very powerful influence, became ill and was hospitalized. Things went downhill from there.

What was your role as secretary of the selection committee? In the early stages I did not play a significant role. I was busy with other duties. But then the events of Tiananmen Square took place and everything was turned upside down. As you recall, the students came out in massive demonstrations. As fate would have it, the number one supporter of the Tiananmen students within the Chinese hierarchy was Yan Min Fu, who also supported the idea of including the Dalai Lama in the Panchen Lama selection process. Tiananmen Square marked the end of his career, and once the smoke cleared, the tentative consultation relationship with the Dalai Lama also collapsed. The Central Government’s principal concern, after Tiananmen Square, was stability. Given the mood of the leaders, there was no way that anyone could pursue contact with His Holiness. It’s a great tragedy, really. If there had been secret contact with His Holiness, the Chinese would have been able to publicly announce the candidates and make it look like it was their idea, and then there probably would have been no problem. Saving face is extremely important in Chinese politics.

But that’s not what happened. From what I understand, there was a little bit of a mistake. His Holiness made a public announcement first, I guess because Dharamsala wanted to demonstrate their authority over the choice of the next Panchen Lama. The Chinese were furious, and everything got very difficult after that. An emergency meeting was convened in Beijing. All the lama members of the religious team came. Right before this meeting, a high-ranking Party official and some of his associates interviewed me and asked me, “What is your opinion? Are you supporting the Central Government or not?” I told them the truth, that I thought that they should include the Dalai Lama in the selection process.

How did the official respond? “This is not negotiable. Luckily you are from Kumbum in Amdo. If you were from Central Tibet, from Tashilunpo Monastery, you would be in big trouble right now! Never say these things again.”

I learned something very important that day. While the Panchen Lama was alive, I felt like a child protected by a father. But during that interview, I realized I was an orphan who had lost all “parental” protection.

What about the emergency meeting held the next day? All of us who were members of the religious team were forced to agree to all the Central Government’s proposals, which included removing the Dalai Lama from the process and agreeing to the Communists’ implementation of a lottery, which would take place at the Jokhang in Lhasa.

I think I should add that during the meeting all of the lamas were silent. But the meeting was filmed, and that night on TV they panned over the lamas with subtitles that said, “So-and-so-lama said this; so-and-so-lama said that!” It was all lies.

In your autobiography you describe the trip to Lhasa as intense and surreal. Yes, even when we landed at Gonggar Airport, we realized that the Central Government was proceeding with a great show of urgency. The terminal was swarming with armed PLA [People’s Liberation Army]. As you know, Gonggar Airport is sixty miles south of Lhasa. Along the way, from the terminal to the Lhasa hotel—on both sides of the road, about fifteen feet apart—there was an armed soldier! All the way to Lhasa!

And that kind of intensity never let up. After we checked into the hotel, we were called together and told: “You will not leave the premises of the hotel. You will not ask friends or associates to come into the hotel to visit. You will be prepared to leave for the ceremony without prior warning. During the ceremony, if any of you act up or do bad things, there will be no excuses and the punishment will be severe.”

About midnight, or maybe one in the morning, we were once again called together. “Time to leave!” they said, and by two in the morning we left the Lhasa hotel. We boarded a bus. The distance couldn’t have been more than fifteen minutes. This time the PLA were on both sides of the road the entire way, shoulder to shoulder—faceless men with helmets, face masks, and big guns and shields. The Chinese were doing everything they could to make it feel like a major historical moment. We entered the Jokhang. The main temple room was already full of witnesses saying prayers: high lamas, local representatives, important monks—I don’t know how long they had been there. The ceilings are very high inside the Jokhang and it’s very dark, even with thousands of butter lamps flickering. But as my eyes became used to the darkness, I realized that around the perimeter of the main temple there were plainclothes police, shoulder to shoulder.

My group was escorted up to the main altar. Directly in front of the main altar, in the position of honor, sat the highest-ranking Communists from Beijing. There was a big table between them and the altar. Perpendicular to the right end of the table was another group of lesser officials. We religious leaders were ushered to the left end of the table and seated facing the lesser officials across the way. I was in the second row. The Karmapa sat directly in front of me and partially blocked my view. Visibility wasn’t great for most of us. Incense was billowing up everywhere. The room was dark, and it was very, very crowded, and on the big table sat the Golden Urn.

Had you ever seen the Golden Urn before? I don’t think any of us had ever seen the Golden Urn before. This was a Chinese thing—something mentioned in old Chinese history books—but I don’t think it was ever used, at least in Tibetan ceremonies. If you go to Chinese temples, you can see these kinds of urns with sticks inside that they once used to divine the future.

The urn they had flown to Lhasa was impressive: bigger than a basketball, with a stem like a goblet’s. Inside, there was a vase within the larger urn. And in this smaller vessel, there were three ivory sticks about a foot long and one inch wide. The nominees’ names had been typed on paper—except for the Dalai Lama’s choice, of course. The altar attendants (they weren’t the regular altar monks) glued the papers to the ivory sticks, pulled tight-fitting gold silk covers down over the sticks, and replaced them in the urn.

Bumi Rinpoche, who was the president of the Buddhist Association of TAR, was asked to come forward and select a stick. He did as he was told, then handed it to the head official, who, after inspecting it, handed it over to the official next to him, and so on, over to the next representative from Beijing.

The event was televised. Later, when we saw the video on TV, we could easily see that the stick that was chosen was a little longer the others. Obviously, this raised everyone’s suspicions—not that we weren’t already suspicious.

So you returned to Beijing demoralized? It was not a happy time. And sometime later, after we returned from Lhasa, officials came to me and offered me the position of tutor to the new Panchen Lama. They said I was going to gain a lot of prestige and power, if I would accept. Of course it was not really an invitation. It was an order. They said, “Anyway, you have to be his tutor because your uncle, Gyayak Rinpoche, was the previous Panchen Lama’s tutor. He did a wonderful job. Now you have to do a wonderful job.”

I realized that I had reached the end of the road. The only thing left for me to do was to defect. Four of the people closest to me escaped with me. It was a complicated escape route. First we went south and eventually ended up in Guatemala. We were hoping to get visas to the United States, but it took a long time. In the meantime, we had to be on our guard. I could be kidnapped and forced back to China, or who knows? Finally, we were cleared to go to America. That was 1998.

I arrived in New York City about the same time as the Dalai Lama did; he was scheduled to give a teaching in Manhattan. It was the first time I had seen the Dalai Lama since 1954, when he briefly passed through Kumbum on his way to Beijing.

You had a private meeting with him in New York? Yes, and I was shocked by what he told me. You see, up until that moment, I had only been thinking about getting away from the Chinese safely, and hoping that the people I had left behind were going to be okay. I really hadn’t thought about what my escape might mean to other people outside of the People’s Republic of China.

When I had my meeting with His Holiness, he told me, “In the eyes of the Chinese, except for my escape, your defection is the most politically sensitive escape they have ever had to deal with. You shouldn’t criticize them or denounce them. Don’t do that. You should try to keep a good relationship with them. Write to Beijing and try to reestablish your relationship with them. Make this connection.”

I had just escaped! The last thing I wanted to do was to have contact with them! I hadn’t thought about all the political ramifications. But the Dalai Lama was right: Good relations might be beneficial for the Tibetan people, no matter what I personally believed. And the future of our Tibetan society was more important. So I wrote to Beijing.

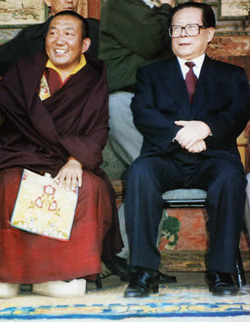

Did you get a reply? Eventually. It was strange. I received a poem from the President of China at that time, Jiang Zemin.

President Jiang Zemin wrote you a poem? Yes, a poem about how wonderful Kumbum Monastery was. “A hundred thousand buddhas have gathered here. So why have you left?” it said, or something like that. “The town is beautiful and the Lotus Mountain is in the background. What kind of nice place are you searching for? You had such a high position in China. Do you have an equally high position in America? Do you think that the Government in Exile will really believe that you are now on their side?”

This was Jiang Zemin’s way of inviting you back to China? Well, yes, the implication was that I would be better off if I returned. And in fact, the Chinese left my position open for a couple of years after that, so I guess they hoped that I would eventually come back, even though I had sought and received political asylum here in the United States.

Have you avoided politics since then? Yes. His Holiness asked me to come here to Bloomington two years ago, and the TCC is strictly nonpolitical. TCC is not an anti-Chinese organization. The question and real challenge for the TCC is: How do we maintain the Tibetan traditions and culture in twenty-first-century America? I don’t know. It’s not going to be easy. But at least we have to try. TCC is a place for healing and hope.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.