Throughout its history Buddhism has regarded the establishment of a monastic sangha—of at least five bhikkus, or ordained monastics—as the indispensable condition for a country to qualify as a place where the dharma has taken root. Symbolically, such a community represents the living presence of the Buddha’s dispensation; in real terms, it shows a society sufficiently conscious of the value of the dharma to support a community of men and women dedicated to its practice. Chithurst Forest Monastery is the first such community to be run entirely by Western monks and nuns, with the wholehearted backing of an orthodox tradition.

At Wat Pah Cittiviveka or Chithurst Forest Monastery, dawn awakes with the faint cry of a rooster and, moments later, cobalt-blue light smoldering in the panes of the Victorian bay window, sharpening the golden gleam of the Buddha’s forehead. Floorboards creak, radiators strain and clunk, as nine shaven-headed monks sit immobile, cross-legged, wrapped in creased ocher robes. Lone birds stammer out their first notes. The cooing of wood pigeons entreats them back to sleep. A cluster of leaves presses against a corner pane. The kitchen clatter of ill-fitting lids on aluminum pots signals the preparation of gruel.

Related: an English country house with Romantic roots becomes home to a Buddhist community

Chithurst is a converted nineteenth-century manor house situated amidst the pastoral affluence of West Sussex, England. These monks were born in America, Britain, Switzerland, and Latvia, but their spiritual roots go back to Magadha, the prosperous kingdom of northern India where the Buddha attained awakening and taught for most of his life. Their presence in Europe can be traced, via a meandering two-thousand-year trail through Ceylon and Thailand, to the missions of Ashoka, the Buddhist emperor of the third century B.C.E. who unified India and established Buddhism as the dominant religion of the subcontinent.

The Arhat Mahinda, son of Ashoka, introduced Buddhism to Ceylon around 250 B.C.E. One of his first tasks was to construct a sima—the formal boundary for monastic ordination—with the king himself driving a plough along the lines drawn out by the monks. Then he ordained the first Ceylonese bhikkus (monks), declaring that Buddhism could not be said to have taken root in the land until native Ceylonese had ordained and could recite the monastic rule (Vinaya). Shortly afterward, his sister Sanghamitta arrived in the island to institute the order of bhikkunis (nuns).

Of the two strands into which Buddhism was dividing at the time of Ashoka, Mahinda and Sanghamitta represented the tradition of the Elders (Sthavira) rather than that of the Majority (Mahasamghika). During Ashoka’s reign the first major rupture occurred in the Buddhist community; Ashoka convened a council at his capital, Pataliputra (modern Patna), to settle it. While outwardly the dispute between the Elders and the Majority concerned doctrinal differences, inwardly it concerned a more fundamental divergence over the nature of authority and the ordering of spiritual priorities. The Majority demanded a greater say in the running of the community for the ordinary, imperfect monks—even, it seems, for the laity. For the Elders, such democratic tendencies were felt to threaten the very authority they believed to have been invested in them by the Buddha. Ashoka’s council was unable to resolve this dispute, and the two sides went their own ways—ultimately resulting in the confusing division into the so-called “Hinayana” and “Mahayana” traditions of Buddhism that persists to this day. Over the centuries the Elders developed into numerous branches, the most resilient of which proved to be the Theravada, now the established school of Sri Lanka and much of Southeast Asia.

One of the first glimpses Europe received of such Theravada Buddhist monasticism was from Jean Marignolli, an envoy of Pope Benedict XII (1334-42), who, having been dispatched to China in 1338, returned home via Ceylon and wrote of the bhikkus:

These monks only eat once a day and never more and drink nothing but milk and water. They never keep food with them overnight. They sleep on the bare ground. They walk barefoot, with a stick, and are satisfied with a robe rather like that of our Friars Minor [Franciscans], but without a hood and with a cloak over their shoulder in the manner of the apostles. Every morning, they go in a procession to ask, with the greatest possible reverence, that rice be given them in a appropriate quantity for their number….I speak of these things as a witness and, in truth, they welcomed me as if I had been one of them….These people lead a very saintly life—albeit without Faith.

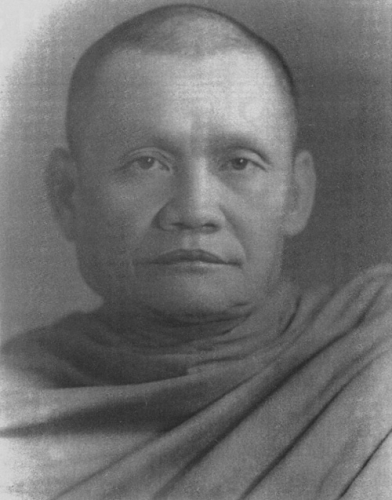

It was into such a Buddhist culture, little changed in the intervening seven hundred years, that Ajahn Chah was born on June 17, 1918, to a prosperous family in a village in the forested northeast of Thailand. After receiving monastic ordination at the age of twenty-one, he embarked on the usual course of studies in Buddhist doctrine and the Pali language. When his father died five years later, he realized that his learning had brought him no closer to the end of suffering. In 1946 he set off on foot with nothing but his robes, an alms bowl, and the minimal requisites of a monk in search of a way of life more conducive to discovering the freedom of nirvana. This quest led him to place greater emphasis on the monastic rule, which in the towns and cities was often lax, and to seek instruction in the practice of Buddhism, rather than contenting himself with knowledge of its doctrines.

H

is dilemma reflected a conflict that had beset the Theravada tradition throughout its history in Ceylon and Thailand. State support meant that the Buddhist order was guaranteed the material and social security needed to ensure the preservation of the dharma. But in return the monks were to serve the interests of the State by establishing a moral and spiritual framework whereby the people would live in harmony and obedience. This caused the order to fracture into two parts: “forest monks,” who placed a premium on realizing nirvana, and “town monks,” who chose to serve as village priests, administrators in city temples, or scholars and teachers. Once a bhikku’s role as a cleric superseded his religious aspirations, the very raison-d’etre of being a monk—”that suffering may cease and further suffering may not arise”—was undermined. Observation of the rule became largely a formality that went with the job, and the practice of meditation became a luxury for which there was little time and interest.

Such concerns led Ajahn Chah to the renowned meditation master Ajahn Mun. Although he spent very little time with this teacher, he learned something that transformed his understanding of Buddhism: the true way of practice lies in mindfully seeing that everything arises in ones own heart. This insight inspired him to spend the next seven years following the austere disciplines of the Forest Tradition, wandering through the countryside and meditating in jungles. In 1954 he returned to his home village and settled in the nearby woodland. His presence drew other monks to follow his example, and they founded a monastery that came to be known as Wat Pah Bong.

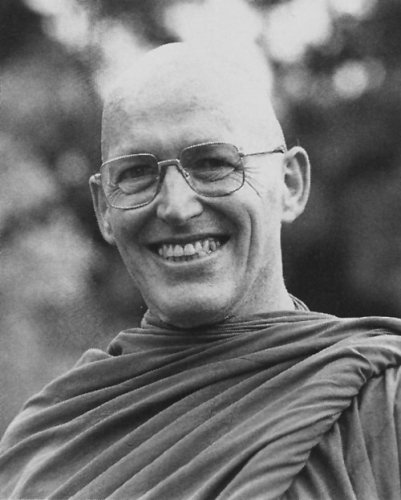

It was to Wat Pah Bong that a newly ordained American monk, Ven. Sumedho, was taken to meet Ajahn Chah in 1967. In his former existence as Robert Jackman, Sumedho had served as a medical officer in the Korean War, completed a degree in South Asian Studies at U.C. Berkeley, and taught English with the Peace Corps in Borneo. His first year as a novice in Thailand had been spent mainly in solitary retreat, where he had experienced an overwhelming sense of spiritual well-being but found himself incapable of coping with other people. Sumedho spent the next ten years under the guidance of this kind, humorous but uncompromising teacher, learning the principles that underlay Ajahn Chah’s approach: living harmoniously in a community, practicing mindfulness under all conditions, and ceaselessly letting go of clinging and conceit.

By 1974 the number of Westerners arriving to ordain and practice with Ajahn Chah led to the founding of Wat Pah Nanachat, a monastery dedicated to the training of Western monks. Sumedho was appointed abbot, the first Westerner to hold such a post in Thailand. But in 1977 this idyll in the Thai jungle was interrupted. Ajahn Chah received an invitation to the U.K. from the English Sangha Trust, a lay organization that since 1955 had been trying, as yet unsuccessfully, to establish an order of Western Buddhist monks in Britain.

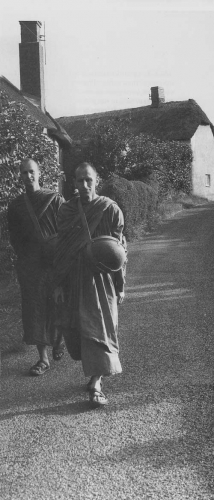

Ajahn Chah arrived in London with Sumedho, and left his American disciple—now Ajahn Sumedho—behind to take charge of three other Western bhikkus in the Vihara, a cramped house in the less salubrious end of London that rattled with the groan of passing traffic. Sumedho was firmly committed to the need for a monastic sangha.

One morning the following spring, while out on the daily ritual with their begging bowls in search of nonexistent alms, the bhikkus attracted the attention of a jogger on Hampstead Heath who offered them a forest. Hammer Wood in West Sussex had been bought with the intention to restore it to its original state. Recently the jogger had realized that his plan was too ambitious to accomplish unassisted. Although not a Buddhist himself, he felt that these monks would be ideal wardens. Bylaws, however, forbade any permanent structures to be built in the wood. The forest monks had a forest but nowhere to live. So the following year the English Sangha Trust sold the Hampstead house and purchased a dilapidated Victorian one about a mile from the woodland in the village of Chithurst.

T

he previous owners had let Chithurst House fall into ruin over the years, retreating from the leaking roofs and decaying floors until only four of the twenty or so rooms were habitable. The electricity had long since failed, only one cold water tap worked, dry rot infested the woodwork, the cesspool had not been emptied for twenty-five years, and more than thirty abandoned cars littered the gardens. For two years they put aside their monastic routines and turned into builders, carpenters, metalworkers, and plumbers, pausing for contemplation only during the Rains Retreat or when funds ran out.

In 1981 three events signaled, if not completion of their task, at least that its end was in sight. In February, the radiant half-ton golden Buddha arrived as a gift from a devout lay-supporter in Thailand and was maneuvered into the newly prepared shrine room. On June 3, Ven. Anandametteya, an elder from Sri Lanka, established a sima (monastic boundary) in the garden and conferred on Ajahn Sumedho the authority to perform ordinations. And on July 16 the first Theravada Buddhist ordination in Europe to be carried out by a Westerner took place as Ajahn Sumedho ordained three Western postulants as bhikkus.

This flourishing of Buddhism in Sussex coincided with the collapse of Ajahn Chah’s health in Thailand. Earlier that summer the diabetes that had affected him for years became suddenly worse and he was rushed to Bangkok for an operation. This was of little help. By the autumn he had lost his speech and shortly afterward the use of his limbs. By the end of the year he was paralyzed and bedridden.

For the next ten years, his comatose existence was maintained by his disciples in a custom-built clinic in the forest at Wat Pah Bong. Paradoxically, during the period he had been silenced by disease the number of monasteries inspired by his example grew to nearly a hundred worldwide. On January 15, 1992, Ajahn Chah died.

By the time of his death, Chithurst House had been immaculately restored in every detail, from the spiraling brick chimneys to the well tended lawns, from the scrupulously polished floors up to the caringly re-crafted banisters. Radio, television, and newspapers are forgotten rather than banished, days are regulated by bells and lunar cycles instead of clocks and calendars, and a vital stillness absorbs anxiety and precipitates “wise reflection on the dharma,” silent meditation, bowing, and chanting: in short, a life of awareness.

Its success has surprised not only skeptic outsiders, but even members of the English Sangha Trust. The very notion of shaven-headed bhikkus in thin cotton robes and sandals going on a daily alms-round through English towns and villages, where not only Buddhism but monasticism and mendicancy in general are alien, seemed ludicrous. Surely the sensible thing to do would be to modify certain aspects of the monastic rule so that the contrast between the monks and the rest of society would be lessened. But Ajahn Chah and Ajahn Sumedho—as well as the ethnic Thai community in Britain—would hear nothing of it. If change comes, it will come in its own time, they said. Our sole task is to place unconditional trust in the rule of the dharma. If the conditions are ripe in Europe, it will work; if not, then we’ll go back to Thailand.

It is noteworthy that despite the current level of interest in Buddhism in America, a Theravada monastic community such as Chithurst has not yet been established. It is equally ironic that it took an American—Ajahn Sumedho—to provide the inspiration and resolve to create the monastery at Chithurst, and subsequently, branch monasteries elsewhere in Britain, Switzerland, Italy, and New Zealand. The Theravada tradition in the U.S. has so far been primarily a lay movement, headed by teachers such as Jack Kornfield (himself formerly a bhikku with Ajahn Chah) and Joseph Goldstein, who have presented the Theravada teachings through their highly successful vipassana meditation retreats.

Related: a teaching from Jack Kornfield inspired by his time at Ajahn Chah’s forest monastery

At the root of Chithurst Monastery lies the encounter between Ajahn Chah and the straggling procession of disaffected Westerners who drifted into Thailand during the sixties and seventies. Ajahn Chah, himself a rebel against the lax clerical Buddhist establishment of the towns, appealed to these veterans of the hippy trail and the Vietnam War as someone who offered not only a radically simple and sane philosophy of life but an embodiment of it in his daily existence. The austere lifestyle he followed was infused not with the dour, world-denying outlook one might expect but with a sparkling, roguish, and above all contented personality. Years of hedonistic excess, together with a loss of faith in Christianity, had led these young Europeans and Americans not to unfettered freedom but to spiritual despair. And this pot-bellied little monk, who looked more like a bullfrog than a saint, turned their worldview on its head.

The long hair and beards were shaved off, the embroidered Afghan shirts and baggy Indian trousers were exchanged for hand-dyed ocher robes, and total unrestraint was replaced by 227 rules of conduct. “I know that you have had a background of material comfort and outward freedom,” Ajahn Chah would tell them:

By comparison you now live an austere existence. Food and climate are different from your home….This is the suffering that leads to the end of suffering. This is how you learn….I know some of you are well educated and very knowledgeable. People with little education and worldly knowledge can practice easily. But it is as if you Westerners have a very large house to clean. When you have cleaned the house, you will have a big living space. But you must be patient.

T

he explicit emphasis on a simple and harmonious community life and the implicit need to train with a teacher wiser than oneself are at the basis of Ajahn Chah’s understanding. No matter how uncomfortable or irrational the monastic rule may seem at times, unconditional confidence that it is vital to Buddhist practice is the act offaith upon which the community is founded. The danger of it’s becoming constricting and legalistic is avoided by emphasizing moment-to-moment examination of the mind and letting go of fixations. This combination of literal adherence to the rule with open-minded, warm-hearted awareness not only endeared Ajahn Chah to his Western disciples but also endears the monks and nuns at Chithurst to the lay community that supports them. Thus a relationship of mutual, freely offered provision is established: the community gives spiritual nourishment to the laity, and the laity provide nourishment for the monks and nuns.

If you want to really see for yourself what the Buddha was talking about,” Ajahn Chah would say, “you don’t need to bother with books. Watch your own mind.” This non-scholastic, experience-based approach to Buddhism is central to the community at Chithurst. It does not mean that books are forbidden—there is an extensive library of Buddhist scriptures in the monastery—but it teaches one to treat intellectual knowledge with caution. The absence of emphasis on Pali texts, especially the commentarial literature, has freed the Thai forest tradition to follow a strand of the Buddha’s teaching which receives only scant attention in the recorded discourses: “This mind, monks,” said the Buddha, “is luminous, but it is defiled by taints that come from without.” In contrast to many Theravada Buddhist teachers, who tend to speak in terms of “nonself” and “nirvana,” Ajahn Chah, following his teacher Ajahn Mun, uses expressions like “true mind” to designate a basic dimension of being that neither arises nor passes away; it just is:

About this mind…in truth there is nothing really wrong with it. It is intrinsically pure. Within itself it is already peaceful. Our practice is simply to see the Original Mind. So we must train the mind to know the sense impressions, and not get lost in them. To make it peaceful. Just this is the aim of all this difficult practice we put ourselves through.

For a mind on the edge of nihilism, traditional Buddhist doctrines of non-self and emptiness can seem threatening. To be told that fundamentally you are sane, radiant, and at peace with yourself provides metaphors of reassurance with which to build a non-egoistic self-confidence as the basis for ethical and meditative practice.

Related: Why the Doctrine of No-Self Is Not Nihilistic

Ajahn Chah is fully aware of the dangers of reification, of turning the “Original Mind” into a subtle kind of self-centeredness. When once asked whether something really did exist independently from the changing processes of body and mind, he replied:

There isn’t anything and we don’t call it any thing—that’s all there is to it! Be finished with all of it. Even the knowing doesn’t belong to anybody, so be finished with that, too! Consciousness is not an individual, not a being, not a self, not an other, so finish with that—and finish with everything! There is nothing worth wanting! It’s all just a load of trouble….You can call it “Original Mind” if you insist. You can call it whatever you like…

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.