After bowing countless times, I had lost the feel for it. I was stuck. It was not altogether surprising, as this stuckness had been building in me for a while. But the timing was awkward. I was in the shrine hall of a Tibetan Buddhist retreat center in upstate New York, waiting for my teacher, Phakchok Rinpoche. Fellow students stood all around me, backs slightly bent and hands pressed together in anjali mudra. Once he arrived and sat down, everyone would bow their heads to the floor three times. I wasn’t sure what to do.

I had first met Rinpoche a decade earlier, in 2002, while living with my family in Kathmandu. I was curious about Tibetan Buddhism, and since we were the same age, I thought he might be a good person to talk to. I walked across the city to his grandfather’s monastery and was shown to a small room on the second floor. Rinpoche sat cross-legged on a low couch, dressed in maroon robes. His moonlike face lit up the room, but his dark eyes sized me up. I bowed, awkwardly, and sat down on a colorful woven carpet. I didn’t really know where to begin.

Rinpoche’s attendant brought us tea, and we talked about Buddhism. I was immediately drawn to his philosophical perspectives, as they informed my own ruminations about the role of the mind in shaping reality and where to find purpose in a world that felt so fleeting. From time to time, a monk came into the room to clarify a topic related to meditation or to explore the finer points of a text he was studying. Sipping my tea, I sensed I had stumbled upon an entire tradition concerned with questions I had thought were purely personal.

Nepal tugged at me even after I returned home and finished college. Before leaving, Rinpoche had given me a small painting of a Tibetan saint that I hung on my wall. It conjured up memories of a different way of life. I still didn’t know much about Tibetan Buddhism, but I had picked up a couple of books: The Snow Lion’s Turquoise Mane: Wisdom Tales from Tibet and Words of My Perfect Teacher, a translation of a 19th-century guide to a set of foundational practices known as the ngondro. These practices seemed like a portal into the lived world of Tibetan Buddhism, and, eventually, I returned to Nepal to do them myself.

Starting with full-body prostrations, each ngondro practice is typically performed 100,000 times or more. To do a single prostration, one drops from a standing posture, brings both knees down onto a slightly raised wooden platform, and then slides the entire body forward. I enjoyed the repetition and the physicality of the practice. From time to time, the old monks and nuns who lived in the same mountain hermitage would pop into the shrine hall and nod approvingly as I performed my prostrations. After months of bowing for hours each day, I finally completed my 100,000th prostration, and we all celebrated with delicious milk tea. The following day, I eagerly began the next phase of the ngondro.

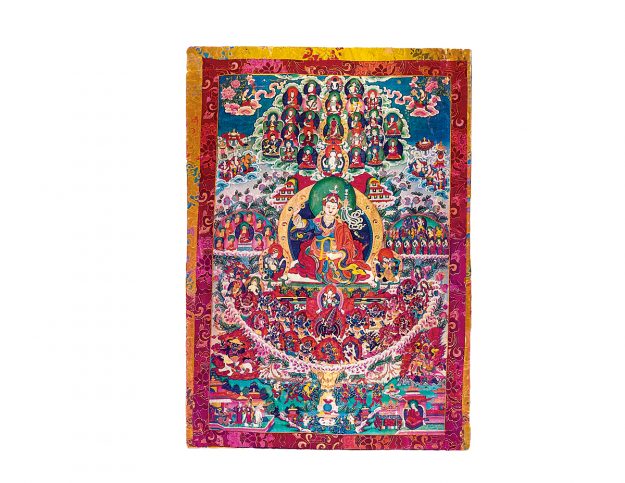

The foundational practices have a lively, imaginative dimension. While doing them, I visualized an elaborate refuge tree, filled with Buddhist deities and masters. Padmasambhava, who is widely credited with bringing the tantric teachings to Tibet in the 8th century, is the central figure. He is flanked by Shakyamuni Buddha, his disciples, and a group of bodhisattvas. Below is an array of wrathful deities, and above sit celestial beings intermingled with Indian and Tibetan masters of the past—the patriarchs of Phakchok Rinpoche’s lineage. Indeed, a key aspect of the ngondro was imagining Rinpoche as inseparable from these enlightened beings.

Guru yoga is the final and most essential part of the ngondro. In this practice, all the beings in the refuge tree dissolve into the central figure, who symbolizes one’s teacher. After supplicating, one imaginatively receives blessings and merges with the teacher’s awakened mind. Guru yoga is the bridge between the foundational practices and the rest of the Tibetan Buddhist path; it embodies the ethos of the tradition.

In light of the ngondro practices, I saw Rinpoche not only as a spiritual friend but as someone to be held in the greatest esteem—as a tulku, an incarnate lama. When he visited the hermitage, everyone welcomed him with great ceremony. I anticipated these opportunities to meet and discuss my practice. In those moments together, I, too, felt special.

The foundational practices are the basis for advanced tantric ritual and meditation practice, but they are also considered transformative in their own right. Tibetan Buddhists—including many renowned masters—often continue to do them throughout their entire lives. I was inspired by this approach. However arduous, the practices immersed me in the devotional life of Tibetan Buddhism, whether in a remote hermitage or among the motley group of monastics and laypeople who performed them each morning by the Boudhanath Stupa. Even when I was home in Vermont, working as a schoolteacher, I continued to do the ngondro.

By the time I was standing in the shrine hall in upstate New York, I had completed the foundational practices many times over. I had studied philosophy, learned numerous meditation techniques, and gained some proficiency in the ritual arts. And it wasn’t just Buddhism that had made me feel at home among Tibetans. I came to enjoy tsampa and butter tea. I spoke Tibetan, laughed at jokes, absorbed customs, and committed more than a few faux pas. Despite all this, something in me had started to shift. The very intensity of my engagement with Tibetan Buddhism had made me see that some ways of thinking and belonging would never be mine. Now, I found myself resisting even bowing to the lama—the most basic ritual form.

Over dinner the previous evening, I had discussed this issue with Rinpoche, a sign of my desperation to understand what was happening. I wasn’t against bowing or other ritual forms, but, inexplicably, they no longer felt like the right idiom for expressing my devotion. The practice was like a favorite shirt that no longer fit. Characteristically, he empathized with my situation, saying that at times he had also struggled to follow the protocols expected of him. Unlike so many times before, however, his advice did not get to the heart of what I was feeling. The very intensity of my engagement with Tibetan Buddhism had made me see that some ways of thinking and belonging would never be mine.

And, in this instance, how could I expect his insights to hit the mark? Patiently guiding me through countless ups and downs, Rinpoche had shown kindness and humor at every turn, along with an uncanny intuition for the workings of the mind. But there was one thing he couldn’t fully know: what it’s like to engage in Tibetan Buddhism as a cultural outsider—to not only try to grasp the complexities of another world but also to inhabit its values. As scholar Robert Bellah observes in his essay “The Meaning of Dogen Today,” Dogen could take certain elements of Buddhism for granted; he “is inside a tradition before he has to think about it.” The same could be said of Rinpoche. I, on the other hand, had been trying to figure it out all along. We were never going to be standing in quite the same place.

As I stood there the following morning, wondering what to do, I concluded that I must still have a few more bows left in me. Rinpoche entered the shrine hall and began to slowly walk to the front of the room. I bent forward to bow but then noticed that he was crossing toward me. As he drew near, I straightened up. He leaned over with that familiar smile, whispering in my ear, “Don’t fool yourself!” I had not expected him to weigh in on my dilemma so directly, but I was utterly relieved. His message was clear: If you’re not feeling it, don’t bow.

Among the Vajrayana Buddhist norms that came out of India, following the directives of a guru is particularly important. In many devotional narratives, students willingly obey the guru’s commands—even jumping into fire or breaking laws—fully aware that injury or punishment may follow. Whether told symbolically or literally, these stories illustrate hardships that test a student’s resolve and devotion to the guru’s unfailing guidance. Such stories were told and retold in Tibet to emphasize the importance of obeying the lama.

Phakchok Rinpoche’s suggestion—that I not fool myself when it comes to bowing—gave that logic a reverse spin. Paradoxically, to follow his instruction meant listening to myself. I had long assumed my path was already set, so I adhered to traditional forms. But in the days and weeks that followed, a different outlook emerged. I realized I was at an impasse. The apparent completeness of the Tibetan Buddhist path had given me a clear sense of purpose, yet I found myself increasingly drawn to explore the tradition in ways rarely addressed by Buddhist texts or teachers.

Once, in Kathmandu, a visiting American professor mentioned during a seminar that the Buddha might not have presented the four noble truths in his very first teaching. These core doctrines, he suggested, may have been systematized later in his life, or even codified by his followers after his death. For most of the students, this amounted to a heresy, but for me the idea that the very foundations of Buddhism are uncertain was thrilling. Stepping out of the monastery classroom that day, I wondered how everything around me—the ritual offerings, the chanted liturgies, and the spinning prayer wheels—had come to be part of the tradition.

Seeing Buddhism as historically fluid felt inviting, but for the most part, that wasn’t how I had heard it talked about. Being part of a tradition meant doing things a certain way—and who was I to question that? From bowing to guru yoga, foundational practices entail visualizing the lama as a buddha. Commentarial texts urge practitioners to surrender their perceptual agency and regard all of the lama’s actions as perfect. Relying on the lama often leaves little room for personal interpretation, and this stance is upheld by many contemporary teachers. I understood the ngondro’s importance from within the tradition, yet from a historical viewpoint I had no idea how Tibetan Buddhists came to do these particular practices.

Regarding the ngondro, other Buddhist students were interested in history too: Are the practices Indian or Tibetan? Why these particular forms? Do we really have to do them 100,000 times? Is the traditional ngondro still appropriate for our times? One friend asked an elderly lama whether he could instead do 10,000 of each foundational practice. “I have an old brain,” he kindly responded, suggesting that my friend stick with the larger number. I wondered to myself how long the preliminaries had been done this way. For Tibetan Buddhists, ngondro requires a great deal of time and effort, and questions about how it should be done are far from trivial.

The gap between the givenness of tradition and my own curiosity about how it all came to be became impossible to ignore, eventually leading me to study the history of ngondro in graduate school. I soon discovered that Sanskrit texts prescribe foundational practices different from those done in Tibetan traditions. For much of Tibetan history, even the standard ngondro practices weren’t tied to a fixed number but were instead performed for a specific amount of time or until a sign of accomplishment appeared. The now-common model of doing each practice 100,000 times may not have been standardized until the 18th century. Tradition, I realized, is more varied than I had long assumed.

Tibetan Buddhists, in some cases, explicitly concluded that Indian forms needed to be adapted to their own time and place. In The Profound Path of Guru Yoga, for example, Sakya Pandita (1182–1251)—a Tibetan scholar famed for his knowledge of Sanskrit—cites examples of the legendary hardships endured by Indian Buddhists, and how these trials led them to recognize their guru as a buddha. But he then recounts a conversation with his lama and paternal uncle, Drakpa Gyeltsen (1147–1216), who states that these days such hardships are not viable. Students get upset if a teacher utters one critical word, if a meal is late, or if they have to sit in a low seat. Given all this, Drakpa Gyeltsen rhetorically asks, “What’s the point of practicing hardships?” Ritual practices such as mandala offerings and guru yoga are presented as alternatives to the devotional hardships.

This shift in emphasis is striking. The focus on guru yoga, a practice with no exact precedent in Indian sources, was one of the most significant developments within Tibetan Buddhism. While Indian Buddhist rituals are typically directed toward buddhas, bodhisattvas, and deities, Tibetan guru yoga rituals also center on historical masters, such as Padmasambhava, the Karmapas, and Tsongkhapa. The absence of similar standalone guru yoga liturgies in Indic texts is conspicuous when contrasted with their eventual prominence across all schools in Tibet.

While moving offices recently, I came across the worn image of the refuge tree I had used throughout my time practicing guru yoga. I hadn’t seen it in years, but it felt instantly familiar, etched in my mind from the many hours I had spent visualizing it. The figures depicted are now recognizable to me from an academic perspective as well. The centrality and relative size of Padmasambhava—compared with Shakyamuni, who sits off to the side—struck me as particularly revealing. Focusing on more recent masters seems to have helped localize ritual forms such as guru yoga, situating practitioners within distinctly Tibetan Buddhist traditions.

Indeed, for guru yoga, it seems especially important to have a devotional mirror that reflects one’s sense of place. My own attraction to the practice was fueled by the conviction that if I did it enough, I would eventually experience Tibetan Buddhism from the inside out—that the imaginative merging with the lama would override any sense of cultural difference. Tibetan Buddhism did become part of me, yet something remained just outside the frame. The inherited symbols conveyed in the refuge tree proved difficult to fully internalize, and even now, they remind me that I’ve always been engaging with the tradition as a cultural outsider.

Oscar Wilde famously observed that “life imitates art far more than art imitates life.” Perhaps the same could be said of life and Buddhism. Believing there was a right way to be Buddhist, I spent many years trying to match my experience to an ideal or to Rinpoche’s inspiring example. This approach took me a long way, but in the end, it led to the ironic—and somewhat unsettling—realization that it had been my own journey all along. Studying history made that realization less lonely: Many others have grappled with tradition and made it their own. The path I found through guru yoga is nothing like what I expected, but it still feels like things fell into place.

“Don’t fool yourself.”

Indeed.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.