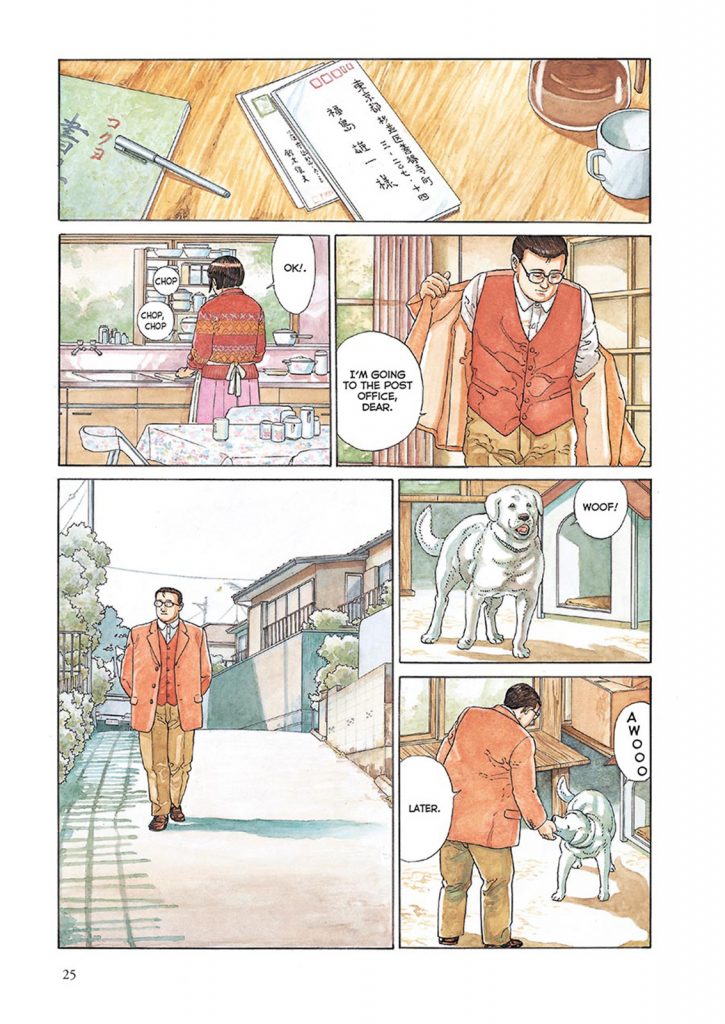

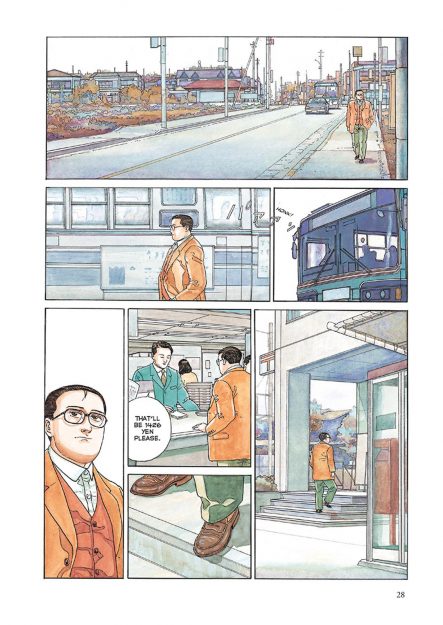

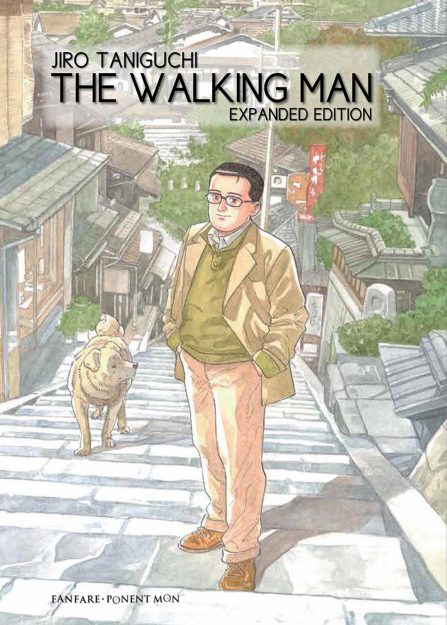

Only a few panels in Jiro Taniguchi’s masterful comic The Walking Man feature any dialogue at all. The plot is so thin that it seems to evaporate upon inspection: A man in a nondescript Japanese town goes on walks. He has a wife. Sometimes he gets off at the wrong train stop. Sometimes he gets caught in the snow. So why is almost every spread of the 232-page graphic novel so unbearably moving?

By Jiro Taniguchi

Ponent Mon, March 2006, 232 pp., $30.00, paper

Unfortunately, it might be Taniguchi’s very slowness and care that have prevented him from garnering more attention in America. Despite being one of Japan’s most celebrated artists when he passed away in 2017, much of his output has remained inaccessible to English-speaking readers until recently. Thankfully, translations of his most-praised work hope to bring attention to one of the medium’s true masters.

What The Walking Man often shows us is how simple life can be when we get down to it. How little we need to be happy: A thick carpet of cherry blossoms. Rain falling on a temple mound. The shattered landscape created by broken glasses. Wading through a puddle shoeless on your way to the train station. A slice of luscious cake. Where is the plotline? The aspiration? The goal? Taniguchi seems to ask: why does there have to be one?

It isn’t only the everyday snatches of delight that have resonance in his work, either. It’s also the struggle. In one chapter titled “A Reed Screen,” our walking man protagonist rambles home through the swelter of summer heat carrying a rolled-up screen. He takes shelter from the sun under a bridge, sweats through his shirt on the roadside, pauses briefly in the scattered sunlight of a forest, and then drenches himself in an outdoor faucet. All in silence. The chapter ends with him back at home, sipping a cold drink next to his wife in the now unfolded shade of the screen.

That’s it. “Isn’t it wonderful?” Taniguchi seems to be saying. “Look at the rhythm and repose of our lives, the great drama that emerges when we simply pay attention.” And yet he’s never didactic, hammering you over the head with a lesson about being in the moment. There isn’t enough dialogue for that to be the case. Instead, each chapter serves more as a reminder. We already knew that all of this lay at the heart of existence. Of course we did.

Zen often has a similar relationship to language and silence. At best, words serve as a means to an end: a finger pointing at the moon of reality. Yet the use of language is fraught. We can get tied up in its concepts, confusing the finger pointing at the moon for the moon itself. Zen philosopher Shizuteru Ueda describes this tricky give-and-take when he says we’re always dynamically “exiting language and exiting into language.”

Taniguchi’s most recently translated work, The Solitary Gourmet, revolves around a wandering salesman who experiences a similar movement from language into silence. Each chapter centers on a different restaurant our protagonist has stumbled into.

Often, he begins these episodes like a hungry ghost, his mind swirling with thoughts: He’s harried by his busy day at work. He’s starving. The weather is lousy. But eventually he settles into his chair, he overhears the patter of the regulars. Language melts away entirely. “Something is different here,” he thinks in one such moment. “The flow of time is completely different than in my own business.”

What’s different is that for a fleeting moment, this character has become unencumbered by words and their illusions. He forgets about his hunger, both literal and spiritual. And without all of that baggage, he’s able to find a pocket of stillness where he can care more deeply about the world around him. “What’s going to happen to the man running that [bakery] in the future?” he thinks in a later chapter while driving below a statue of Kannon, the bodhisattva of compassion. “He said his wife’s health was bad… In another five, ten years… He’ll be all alone… In this town…”

Then he trails off into silence.

Taniguchi and his wandering protagonists keep drawing away from language like this. That they’re always pulled back into a relationship with words doesn’t make the exit any less important. In the silent episodes of the solitary gourmet’s life, in the walking man’s quiet appreciation for just being, we’re reminded that no matter how often we fall for the tricks of attachment, life will always be here for us when we quiet our minds.

It brings to mind Henry Shukman’s memoir One Blade of Grass, which explains that Zen commands such as just walk don’t mean “keep your mind only on walking and don’t think about anything else.” Rather, they’re saying “there is no mind to put on walking. There is only walking.” And this is what Taniguchi captures in his work. His protagonists are not fighting to find mindfulness amidst the whirlwind of existence. Rather, they become the very thing they do. Just walking. Just eating. Just being.

And this returns us to the initial question: how does Taniguchi manage to move us so deeply through his silence? Why does his depiction of, say, a raindrop hitting a leaf stir more tenderness than such a sight often does in our own lives? Perhaps it’s that, in the former case, someone like him cared enough to draw the thing. He observed the way water moves, studied the patterns of leaves, and spent the quiet hours of his days trying to communicate his depth of feeling. Like his protagonists, he found a little bit of stillness and used it to surround the world with his own heart.

Long after we’ve set his books aside, their wordless resonance stays with us.

But The Walking Man, The Solitary Gourmet, and many more of Taniguchi’s works invite us to make this creative leap on our own time. Long after we’ve set his books aside, their wordless resonance stays with us. We should try caring about the world ourselves, they seem to suggest. After all, how hard can it be to take in the small wonders of life on a stroll through the neighborhood?

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.