Thoughts on the East

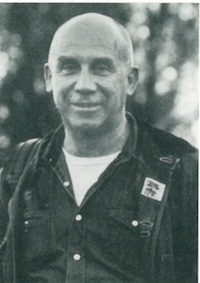

Thomas Merton

Introduction by George Woodcock New Directions, New York, 1995.

75 pp., $6.00 (paper).

Given the views on Buddhism offered recently by Pope John Paul 11 in his book Crossing the Threshold of Hope, it is ironic that so much of my literary introduction to the philosophies of Asia came from the pen of a monk in one of Catholicism’s strictest orders, the Cistercians (more commonly known as Trappists). Before Thomas Merton began writing on Asian philosophy and spiritual practice in the mid-sixties, he rarely ventured out from his monastery in Kentucky. He had, however, already established himself not only as an original thinker whose prose works—like Seven Storey Mountain and New Seeds of Contemplation—had a wide general readership, but also as a very fine poet. This aspect of Merton’s great body of work remains neglected in our time.

Merton began his short series of works on Asian religious traditions as late as 1965, less than four years before his death, although he had been in touch with D. T. Suzukias early as 1961 and had also been reading Aldous Huxley and others on mysticaI traditions. He was a peculiar monastic, and one who refused to confine his world behind monastery walls. He greatly admired both Gandhi and Martin Luther King and, having worked briefly as a social worker in Harlem, was deeply concerned with the civil rights movement of the sixties. And it was through his interest in nonviolent resistance that he even tually turned to the Bhagavad Gita and began his Asian studies.

Drawing from all of Menon’s Asian books, George Woodcock has editedThoughts on the East, a concise introduction to Merton’s oeuvre, with chapters on Taoism, Zen, Hinduism, Sufism, and on “Varieties of Buddhism,” including Merton’s notes on conversations with the Dalai Lama. Like Merton, however, Woodcock died before completing his work,and several of the chapter introductions were prepared by the staff at New Directions.

Thoughts on the East should not be taken as a scholarly introduction to Asian religious and philosophical practices. Rather, it is a subjective and deeply personal meditation by a Trappist monk who in all likelihood never practiced zazen in the traditional sense and who indeed understood shunyata, the teaching that things are devoid of self-nature, only as an intellectual concept. Merton the Trappist could understand meditation only in the sense that “the religious contemplation of God is a transcendent and religious gift.” He would write in New Seeds of Contemplation: “It is not we who choose to awaken ourselves, but God Who chooses to awaken us.” And yet he believed that certain traditional mystical threads transcend culture and religion to open human consciousness.

Following a prefatory comment on Taoism are five “imitations,” or “free interpretative readings of characteristic passages” that held “special appeal” to Merton. In “Perfect Joy,” he captures an essential element of Chuang Tzu. “The ambitious run day and night in pursuit of honors, constantly in anguish about the success of their plans, dreading the miscalculation that may wreck everything. Thus they are alienated from themselves, exhausting their real life in service of the shadow created by their insatiable hope. . . . Perfect joy is without joy. Perfect praise is to be without praise.” In “Where is Tao?” Merton transforms one of the most famous conversations of Chuang Tzu into a poem in which Master Tung Kwo questions Chuang, who in turn says that the Tao is found in the ant, in the weeds, in a turd. “None of your questions,” Chuang says, “Are to the point. They are like questions/ Of inspectors in the market,/ Testing the weight of pigs/ By prodding them in their thinnest parts./ Why look for Tao by going ‘down the scale of being’/ As if that which we call ‘least’/ Had less of Tao?/ Tao is Great in all things,/ Complete in all, Universal in all,/ Whole in all.” Merton’s syntactical model for this structure follows a direct line from the Bible to Blake to Whitman while presenting a respectable Chuang Tzu.

Merton also glimpsed a degree of seriousness and difficulty in Zen practice that few Westerners without formal monastic training could have seen. “The Zen tradition absolutely refuses to tolerate any abstract or theoretical answer to it. In fact, it must be said at the outset that philosophically or dogmatically speaking, the question [what is Zen?] probably has no satisfactory answer. Zen simply does not lend itself to logical analysis. . . .Zen is therefore not a religion, not a philosophy, not a system of thought, not a doctrine, not an ascesis.” Like most who have addressed this question, he can only list what Zen is not. “It is impossible to attain satori (enlightenment) merely by quietistic inaction or the suppression of thought. Yet at the same time ‘enlightenment’ is not an experience or activity of a thinking and self-conscious subject. Still less is it a vision of Buddha, or an experience of an ‘I-Thou’ relationship with a Supreme Being considered as object of knowledge and perception. However Zen does not deny the existence of a Supreme Being either. It neither affirms nor denies, it simply is. One might say that Zen is the ontological awareness of pure being beyond subject and object,an immediate grasp of being in its ‘suchness’ and ‘thusness.”‘

In a lovely appreciative essay, “On the Significance of the Bhagavad Gita,” Merton addresses one of the main problems facing all Westerners exploring classical Asian spiritual discipline. “The hazard of the spiritual quest is of course that its genuineness cannot be left to our own isolated subjective judgment alone. The fact that I am turned on doesn’t prove anything whatever (Nor does the fact that I am turned off.) We do not simply create our own lives on our own terms. Any attempt to do so is ultimately an affirmation of our individual self as ultimate and supreme. This is self-idolatry which is diametrically opposed to Krishna consciousness or to any other authentic form of religious or metaphysical consciousness. The Gita sees that the basic problem of man is his endemic refusal to live by a will other than his own. For in striving to live enrirely by his own individual will, instead of becoming free, man is enslaved by forces even more exterior and more delusory than his own transient fancies.”

Merton’s firsthand experience with Tibetan Buddhism came through an encounter with a Nyingmapa monk, Sonam Kazi, who urged him to undergo formal initiation. “I am not exactly dizzy with the idea of looking for a magic master but I would certainly like to learn something by experience and it does seem that the Tibetan Buddhists are the only ones who, at present, have a really large number of people who have attained to exrraordinary heights in meditation and contemplation. This does not exclude Zen. But I do feel very much at home with the Tibetans, even though much that appears in books about them seems bizarre if not sinister.”

It is interesting to note that Merton appears not the least concerned about making such assertions based upon limited experience. He had never visited China or Japan, nor had he been to Korea, nor had he any significant firsthand experience with other forms of Buddhism in Asia.

At the end of his life, Merton encountered the Dalai Lama, who cautioned him about the suitability of undertaking rigorous practice outside ofhis own tradition, and Merton’s reflections on those conversations are a closing note toThoughts on the East, followed only by a brief memoir about a visit to Palannaruwa. These two experiences brought him to realize that his “Asian pilgrimage has come clear and purified itself. I mean, I know and have seen what l was obscurely looking for. I don’t know what else remains but I have got beyond the shadow and the disguise. This is Asia in its purity, not covered over with garbage, Asian or European or American, and it is clear, pure, complete. It does not need to be discovered. It is we, Asians included, who need to discover it.”

This closing comment comes from The Asian Journal, published in 1973, but written just days before his untimely death by electrocution in his bath. In the end, the trappist monk who modeled his discipline on that of the desert fathers of early Christianity found in the mountain masters the same spiritual longing, the same spiritual discipline that balanced and informed his own.

Thoughts on the East is a lovely little anthology of Merton’s views on Asian spiritual practice and a lively introduction for the new reader. As someone who read Merton early on, it is strange to realize all these years later that, although I have never been a Christian and am often put off by the pronouncements of the Catholic Church, l owe a debt, as a practicing Zennist, to one of Catholicism’s strictest adherents. After thirty years, l can find all sorts of nits to pick, but it is surprising how deeply engaging Merton remains today, both as a poet and as a spiritual seeker.

Sam Hamill is a Contributing Editor to Tricycle. His book Destination Zero: Poems 1970-1995 was published by White Pine Press.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.