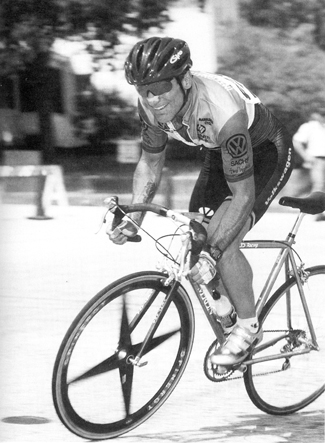

The first thing I noticed about James Veliskakis was the serpentine tattoo running down his arm. We were sitting silently next to each other during a ten-day meditation retreat. We later met at other Buddhist events, and I chatted with him about his passion for bicycle racing, his devotion to Buddhist practice, and his work mentoring youths—but he told me nothing about his pre-dharma life.

At a recent sangha gathering, however, James explained that prior to his encounter with Buddhism, he had been someone none of us would have wanted to know, and he added with chagrin that he would not have wanted to know us either. My curiosity piqued, I cornered him and asked to hear his story. He then regaled me with the details of his earlier life as “Jimmy the Greek” with the Hell’s Angels, the outlaw motorcycle gang. James’s account fascinated me. As a psychotherapist and spiritual seeker, I am always curious about what makes people change and awaken. How does someone go from a lifestyle often characterized by brutality and violence to one with a bodhisattvalike commitment to helping troubled boys and girls? I also wondered in what ways his two paths have been similar. Was the freedom sought by the outlaw the same freedom offered by the dharma? I interviewed James Veliskakis by phone in February of 2003.

—Carla Brennan

Let’s start with some of the details of your past. How did you get involved with the Hell’s Angels? I remember the first time I laid eyes on the Hell’s Angels. I was probably about four years old. It was a bright summer day, but I heard this thunder, and I knew it was coming from the highway near my house, in Peabody, Massachusetts. The next thing I saw was gleaming chrome, and long beards and hair, and black leather. It was bizarre, otherworldly.

It turned out that the Hell’s Angels had a clubhouse right down the street. We’d drive by the clubhouse and we would see them out front. As a kid, I was always on my tricycle. I’d just take off and nothing could stop me. Then later, when I was about nine, I organized my own bicycle gang. I called it “Vel’s Angels.”

Which angels? My last name is Veliskakis, so “Vel’s Angels.” We used to go down to the outdoor mall and terrorize the shoppers—I aspired to be a Hell’s Angel.

By the time I was fourteen, I had dropped my first hit of acid. That was both a blessing and a curse. I walked to a park and I lay down beneath a tree and looked up at the sky. Then the whole world just broke open for me, and I knew life would never be the same. I don’t know if it was some kind of deep spiritual experience or not. But then I started to have bad trips, and I had no one to help me. I sort of lost my identity. That’s when I started drinking, because I was able to overcome a lot of my insecurities and inhibitions with alcohol.

Then I found this gang in Salem called the Gallows Hill gang. They were like the farm team for the Hell’s Angels. I started to wear wristbands and skull rings. The power of the dark side started to appeal to that part of me.

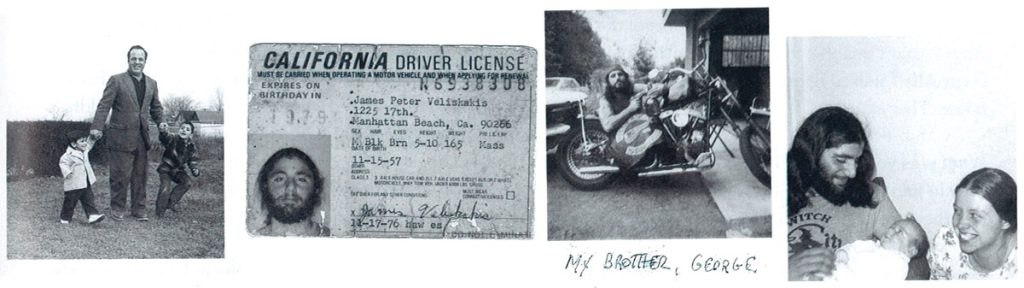

Then my brother became a full member of the Hell’s Angels, and I was able to go on runs with them, and eventually I started living at the Hell’s Angels’ clubhouse. They called me Jimmy the Greek.

What was your family life like then? What role did it play in joining a gang? My parents were from Greece, and they had very traditional values, which they tried to instill in us. My father wanted us to follow in the Greek tradition. My father was steadfast, very hardworking, and he wanted only the best for his family and his sons. But he was also kind of a brutal guy; he was like a dictator. So I had very mixed emotions growing up with him. What he didn’t see coming was living through the sixties with two boys who were karmically drawn to an outlaw, outcast lifestyle. I really loved my father.

You were in jail for a while, weren’t you? Going to prison was part of the deal of being a Hell’s Angel. They always said, “Everybody’s got to do time.” If you didn’t do time, you were kind of untrustworthy because it meant that you might be an informant. Because I had a clean record, I was always the guy who carried all the guns and dope: If I got caught, I would be a first-time offender, so I wouldn’t get a big sentence. I eventually ended up with a court case, charged with assault and battery with a dangerous weapon, a felony. I thought, well, here I go. “Everybody’s got to suffer” was also one of the Hell’s Angels’ favorite sayings. It’s like Buddha’s Number One Noble Truth! The Hell’s Angels knew it. But I got a pretty good lawyer, and we got the case dismissed. Eventually I got my wish and did do some time, but that’s another story.

How did you eventually leave the outlaw motorcycle gang scene? My brother became disillusioned with the Hell’s Angels because of the lack of support he was getting while he was in jail, and I started seeing what was really going on, too: drug dealing, corruption, murder. This destroyed my idealized notion that it was a brotherhood. Also, seeing my father break down in court when my brother received a long prison sentence was heart-wrenching.

I had a vision that to bring me out of the whole Hell’s Angels thing, I first had to purge my body. I learned how to box and trained like a true warrior. I discovered that I no longer needed the intoxication of drugs and drinking. I was training and living the lifestyle of a monk by just isolating myself in the gym.

Can you give an example of a specific incident that made you rethink what you were doing? Yeah. Late one night I left the clubhouse pretty high. A gang of three kids walked toward me. We made eye contact, and I knew something was up. So as soon as I got close enough, I took out my handgun and put it to one guy’s head and said, “You make a fucking move, I’m going to blow your brains out!” They backed down, and I just kept walking home.

The next day when I remembered what had happened, I just went, “Holy shit. What have I got myself into? I don’t know if I’m really like this.” When I was nineteen, my son was born, and I was starting to realize I had responsibilities to someone other than myself. Then my father died suddenly, and I was saddled with the responsibility of running his restaurant and being a caregiver for my mother, and that sort of just sealed it, so I gracefully bowed out. When I was coming out of the fog, I drew this mandala. It was a simple pyramid: mind, body, and spirit. I knew that the body was at the top of the pyramid for me; I knew I had to get clean and in shape before I could work on my mind, and then my spirit. I drew another pyramid within the first pyramid, for forgiveness, love, and acceptance, which made it a star. I was pretty regretful of my actions and started to feel the weight of things I had done. I started to forgive myself. I had this vision that I had exhausted the outlaw part of me, but still there were parts of it that I missed.

What did you miss? There is part of me that misses that complete devotion to living in the moment. Of course, it was more about instant gratification than anything else. But I miss that at the drop of a hat I could be on a motorcycle going anywhere.

It seems that there are many parallels between being in the Hell’s Angels and being on the spiritual path: They both espouse living in the present, freedom, community, testing yourself and being tested by others. You are encouraged to be true to yourself and to live an authentic life. If there is one common thing, it’s that the Hell’s Angels have this zest for life and know there’s more to it than having a job, a family, and pursuing the American Dream. In the moment, they are not regretting anything. And for me, that’s fearlessness. When you are around that you start to feel good, really good.

What do you think draws youth to the Hell’s Angels? It appeals to young people who see a discrepancy between the way life is presented at school and in the media, and the way it actually is. That, for me, was the seed for seeking alternative ways of self-actualizing—and also for taking a very dangerous path.

One thing about the Hell’s Angels, it was a training ground to come into manhood. There’s no room for any kind of bullshit or sweet talk; you get by solely on the integrity of who you are. I needed that. It was a validation that I was worthy. The Hell’s Angels are the number-one outlaw gang, so to be affiliated with that is huge.

After you left the Hell’s Angels, you went back to school and got your college degree, is that right? Up until that point, I only knew how to work with my hands. I’d worked as a fisherman, a truck driver, a carpenter. I decided to get my G.E.D. and sign up for a couple of college classes. Eventually I found my path in social work, and it was like finding the dharma. I started using my past experiences to work with kids who were feeling the same things I had. I tried to intervene in a meaningful way that might make them reflect before they did something that could cause harm to themselves or others. All of a sudden, my past, rather than being something shameful, became my resumé.

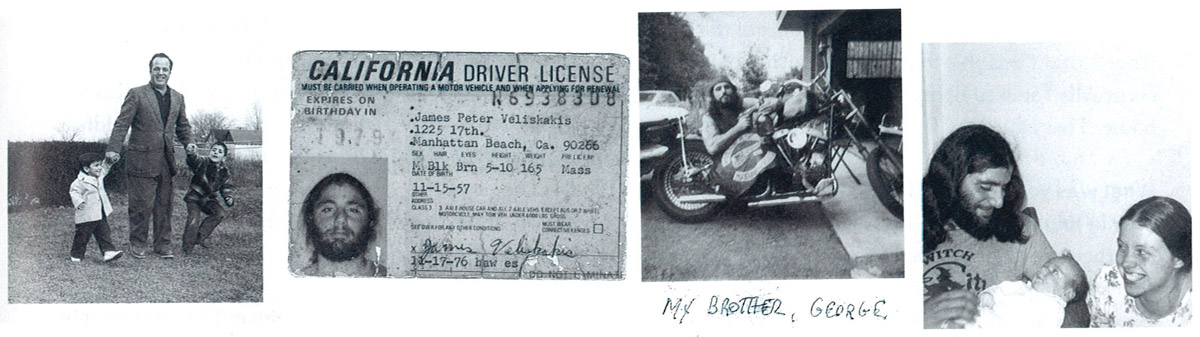

What did school lead to in terms of work? I graduated summa cum laude. I started a mentoring program at an agency that had a budding youth program. I saw the difference in the kids when they were one-on-one versus when they were with a group, and it reminded me of being with the older Hell’s Angels, that closeness and intimacy. These kids would be totally noncompliant and rebellious in the group. Then when I’d get them one-on-one, they’d be so open. The program took off. One of the activities I did with the kids was a bicycle mechanics program. I would teach them basic bicycle mechanics as well as healthy lifestyle and social skills, and they’d end up getting a bike out of the deal.

Is that what you’re doing now? We got funding for the bike program and named it “Tools for the Cycle of Life.” I use the bike and bike-repair lessons as a metaphor for bigger life lessons. We have the “Three Precepts for the Bicycle/Life Mechanic.” The kids always expect some kind of teaching at some point during the class, so I ask, “How can we relate this to our lives?” The kids roll their eyes, “Here he goes again!” But they are all ears at the same time!

I try to put some spin on what we learn: “The spokes of the wheels are like the spokes of our lives: our family, our community, everything that supports us. The center of our existence is the hub. And notice that when the wheel spins, everything is moving except for the center. That’s us, you know. Our wheels need to be true and straight. Be mindful of them, and tighten the spokes in the right way.” I have Om Mani Padme Hum mantras on my own bike wheels.

Like prayer wheels. Yeah, I’m turning prayer wheels when I ride!

So what are your precepts? Precept Number One is that Bicycle Mechanics are skilled at observing and are able to look at a bike and notice right away whether or not it is safe to ride. They are able to maintain the bike and prevent it from breaking down. Life Mechanics, in the same way, are skilled at seeing problems before they arise and become crises. When they see a problem, they attend to it immediately, calmly, effectively.

Precept Number Two is that Bicycle Mechanics know what is beneficial and what is harmful for a bike, what causes it to break down. Likewise, Life Mechanics know what causes happiness and what causes suffering.

Precept Number Three is that Bicycle Mechanics always test their repairs on the road, in real riding conditions. Similarly, Life Mechanics always learn from their experiences. They don’t look at anything as defeat. I started to realize that I had a positive way of influencing kids. If I am looking at a basic bicycle task as if it is a major life-changing event, they are going to look at it that way, too. I try to turn everything into a transformative experience.

You are teaching them basic Buddha-dharma! Right! So we go over what is harmful for a bike, and then what the harmful things are in our lives. Everything’s a teaching, and these kids are constantly giving us golden opportunities to teach them something.

The program sounds exciting and creative and full of opportunities for the kids to learn in ways they don’t even realize. It taps into the kids’ natural inclination to learn and to be part of something. These bikes are in rough shape; these kids are in rough shape. Take some steel wool and put it to those handlebars. What seemed worthless is now a valuable prize.

Can you describe how you were introduced to the dharma? My mother taught me that we are here as the result of something greater. For many years, I’d gone to the Christian Science church because my mother did. Later I was very taken by Native American spirituality. I’d gone to this local shaman, but it just wasn’t quite there for me. They didn’t really have any kind of practice, and that’s what I needed. I had an interest in Buddhism, but as they say, “When the student is ready, the teacher will appear.” Then in 1997 I walked into a bookstore. I saw the book Awakening the Buddha Within by Lama Surya Das. The title grabbed me. Then things just started happening.

What things? As I was reading, I thought, “This is it! It’s all getting clear to me. Somehow, this is all familiar.” Then I heard he was teaching at a conference in Boston, and I knew I had to see him. He started his workshop with the Gate, Gate mantra; I’d never chanted before in my life, but I was full into it. I had been seeing a therapist who was a Buddhist, and when I mentioned that I was going to see Lama Surya Das, she’d said, “He’s great, but I don’t think he’s enlightened.”

So at the end of the workshop, I raised my hand and said to him, “Are you enlightened?” He shot right back, “Yeah, are you?”

Did the whole place laugh? Oh, yeah! They were shocked that somebody would ask this straight out. I thought his answer was great; it was a Hell’s Angel response. I liked this guy! He was able to handle himself.

He asked me again, “So, are you?”

I said, “I don’t know. What does that mean?”

He said, “Have you had a moment of clarity or bliss or feeling completely one with what was going on, that everything was all right as it is?”

I started to remember, as a kid, I’d be in my backyard, by myself, just staring up at the sky, feeling complete contentment and love. “Yeah, I have.” I said.

He said, “That’s the experience of enlightenment.” I thought that was the coolest thing.

At the time, I didn’t know Surya was connected to Cambridge, and he explained that there was a Monday night group there. I said it was kind of a long ride for me and told him where I was from. He said, “What are you saying? I had to go to Tibet to get this! You can go from Peabody to Cambridge; it’s no big deal!” I loved this guy; he totally put me in my place! I went one Monday night and everybody there and the whole atmosphere—it was just right.

I can see why the Vajrayana and Tantric paths are right for you: You are a passionate person, and those paths use that energy for awakening. That’s right. The Vajrayana path is wonderful because it looks at everything as fuel for the fire. A metaphor that I love says that in the beginning, practice is like a candle flame and the slightest breeze can blow it out. After a while, as you start to experience more of the teachings, your practice and your confidence become more like a bonfire. Then a strong wind just creates more fire. You are able to handle all kinds of problems.

These gang members are committed and passionate and fearless; they’ve channeled their energy in a way they think is noble. These gang members are all looking for some kind of spiritual connection; any junkie or heroin addict is in some way trying to relieve their suffering. We’re all in this together, and we’re all trying to seek happiness in our own way. It takes a good, strong spiritual practice to take the drape of illusion off of you.

When I read stories about some of the Buddhist masters who had gone through outlaw lifestyles, I think, right on! These guys were brutal; they were murderers, thieves, whores, you name it. I can connect with this. They went out and lived in the wilderness and didn’t care what people thought of them. It’s Buddha-nature: Everybody’s ready to awaken.

You’ve changed from a lifestyle characterized by ruthlessness and violence to a path of love and compassion. How did your heart open along the way? Well, a part of it is a mystery. Believe me, throughout my time with the Hell’s Angels, I was a loving person. When it came time to be ruthless, I killed the pain of the violence with drugs. When I went to school, I found a way I could finally express myself, and I started to get a glimpse of how I created my own suffering, and how I could use that to open me up to compassion.

What’s your practice now? What do you do every day? My main practices are mandala offering and guru yoga. If I’m feeling guilty or remorseful about my past, I’ll do the confession practice and I’ll offer it up with everything else, my virtues, my vices. It’s the most beautiful practice.

I am grateful to my teachers. I’m also grateful to have support from my family. They’ve seen how it’s transformed me. That’s what I love about Buddhism: Nothing is taken at face value; all the proof is in the pudding. That’s been my biggest discovery. This stuff actually works! It’s like getting hit in the skull with a diamond.

It seems that you believe it is important to plant seeds for others and then help them bring those seeds to fruition. Absolutely. The little things you say or do can become the triggers for others’ awakening. You need to take the time to talk from your depth. What a shame it would be not to take advantage of this life. I reflect back, and I’ve had all these second chances, twentieth chances. If I were to turn away and not try to do something, I would be forsaking all my teachers—and all beings! The greatest gift I can give my teachers is to practice.

Is there anything else that you would like to say that you think might be helpful to others? Find a spiritual practice and stick with it. If you dig a well, you can’t just dig four feet here and four feet over there. You’ve just got to keep digging deep in one place. I feel so lucky and blessed. This life is really precious, you know.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.