What makes a translation work? For poetry and for practice-related texts—pointing-out instructions, oral pith instructions, songs of mystical insight, and even certain sutras—what makes a translation work is the effect it has on the reader. Ideally, when I translate a text, the translation elicits an experience in the reader that is at least an echo of what I experience when I read the original.

Garab Dorje’s Three Lines That Hit the Nail on the Head is probably the most famous pointing-out instruction in the Dzogchen tradition. It is a profound and somewhat enigmatic first-century text that has inspired much commentary and instruction. Numerous translations have been made. I have translated it three or four times myself. None of them, I feel, reflects either the power or the poetry of the original. What, I wondered, would happen if I broke a few conventions and really focused on the experiential quality? In this article, I lift up the hood on the translation process and show you a little of how I go about it, what happens, and what it leads to.

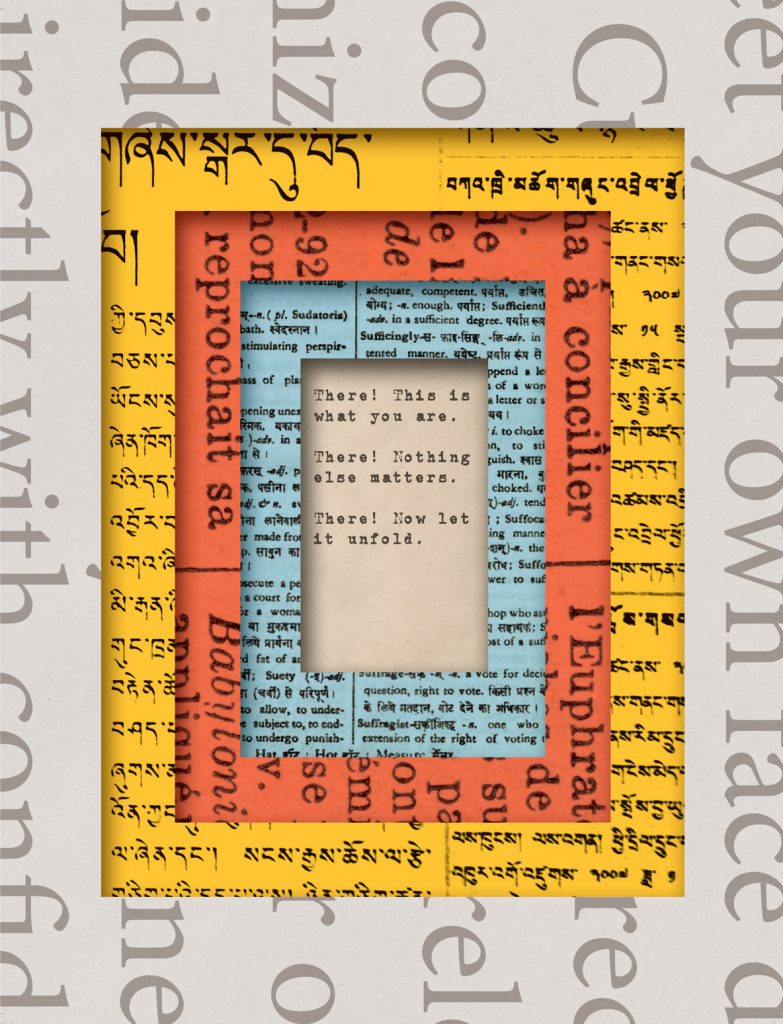

For those of you who know Tibetan, the three lines are these:

ངོོ་རང་ཐོོག་ཏུ་སྤྲད༔

ཐག་གཅིིག་ཐོོག་ཏུ་བཅད༔

གདེེང་གྲོོལ་ཐོོག་ཏུ་བཅའ༔

Tibetan is a monosyllabic language. Almost every syllable is a word in its own right. Because the formal written language was developed to express Buddhist thought and practice, it often takes only a few syllables to express profound instructions and insights. Yet even by Tibetan standards these three lines are extraordinarily dense. They pack a punch in their combination of key technical terms, poetic meter, alliterative emphasis, precise instruction, and experiential impact.

A word-for-word rendering with minimal accommodation to English idiom or grammar might read this way:

Meet your own face directly.

Cut one rope directly.

Go with confidence and release directly.

As they say in business, “Price, quality, service—pick any two.” The same often holds for translation. Literal accuracy, clear meaning, experiential impact—pick any two. In most translations the highest priority is literal accuracy. If the translation conveys the meaning clearly, so much the better. Experiential impact is rarely a consideration. The absence or presence of experiential impact becomes obvious when you read a translation out loud.

From the perspective of literal accuracy, the phrase meet face in the first line is an idiom and is usually rendered in English as “recognize.” “Face” is taken to refer to one’s own mind or mind nature. Thus a typical translation might read “Recognize your own face,” “Recognize your own nature,” or “Recognize mind nature.”

In the second line, Cut a rope is also an idiom. It means “Decide.” Thus we have “Decide on one option.” However, the word “decide” in English is quite a bit weaker than the Tibetan idiom. The Tibetan carries the idea of coming to a decision so deeply that all other options are eliminated. “Conviction” might be one possible rendering, but because one can be convinced about something that is completely wrong, it is not the right word. In an earlier translation, I had tried “Be absolute about one point”—a choice that is accurate in terms of meaning, perhaps, but unattractive in terms of sound and rhythm.

Literal accuracy, clear meaning, experiential impact—pick any two.

Finally, in the third line, the idea is to continue, to keep going, to become familiar with this way of experiencing life. You have recognized your own face or nature. You have decided on the one option. Now you make it part of your life by relying on your confidence in the experience that movements in mind release themselves or let go on their own. The idea of release is often rendered as “liberation,” or “liberate,” but the form of the verb in Tibetan has no agent; there can be no liberator as such. Because an agent is implied by “liberate”— someone or something sets you free—some translations use the term “self-liberate.” It is workable, but I feel that the image is wrong, and with four syllables it is clumsy English. I use the word “release” because, at least in theory, an outer agent is not necessarily implied. A knotted snake unties itself. Thoughts and other movements in mind just let go, seemingly without reason or agent. They vanish as they arise, like drawings on water or snowflakes on a hot stove, when the energy in your attention is at a sufficiently high level. But I am getting ahead of myself a little.

When we choose literal accuracy as our top priority, we usually end up with something like this:

Recognize directly your own nature.

Decide directly on one option.

Continue directly with confidence in release.

This translation has quite a bit going for it. It is clear, to the point, and straightforward. I am being told to take three actions: recognize, decide, and continue. Yet although the translation makes sense, it does not move me. As I think about it, questions arise. What does “recognize directly” mean? It doesn’t sound quite like English. Ditto for “decide directly” and “continue directly.” My own nature— what’s that? One option—what option? Continue with confidence—continue what?

Stumbling blocks are places where the reader starts to think about the words. In writing and in translation, they are problematic, particularly when you are trying to move the reader into a nonconceptual experience.

BACK TO THE DRAWING BOARD.

Now that we have a basic translation, we need to take another look at what we are doing. Is there a way to eliminate these stumbling blocks? Is there a way to make these lines pop with energy? Is there a way to make something happen in the reader? Perhaps we should start with the key ideas—recognize, decide, continue—and see what can be done with those.

Here we run into a peculiarity of English: we have two vocabularies. We have a sophisticated, intellectual, and conceptual vocabulary based on words with Latin roots, most of which came into English after the Norman Conquest. The French invasion did not obliterate the language of the countryside and the streets completely, however. Old English with its Germanic and Norse roots survived, though it first broke up into several regional dialects and then recoalesced into a common tongue. Philosophers, intellectuals, and academics generally gravitate to the Latinate vocabulary because it offers a wide range of precise terminology steeped in classical thought. Poets and writers, however, find that the energy and power of English are in the old language, in words that have Old English, Germanic, or Norse roots.

“Recognize,” “decide,” and “continue” are all Latinate—reconnaître, décider, continuer. They are accurate and precise translations, but they lack power and energy. What to do?

In translation, when I run into difficulty expressing something in English, I go back to the Tibetan and go deeper into the meaning. What does it mean to recognize your own nature, your own mind, your own face? What experience does this refer to? Where in life do we find ourselves committing to one option and eliminating all others? What does it mean to have the confidence that thoughts and emotions release themselves in the groundlessness of experience? And what about this “directly”? What’s going on with that?

“Directly” is the one word that is repeated in each line. The Tibetan is ཐོག་ཏུ (pronounced tok tu). It means “directly” or “immediately.” Again, we run into those vocabulary issues: Both these words are Latinate and both have lots of syllables. They are adverbs, too. You lose power in writing and speaking when you use too many words, too many syllables, or too many adverbs. Here we are translating pointing out instructions, which are pithy, poetic, and punchy. How do we point something out in English and deliver a punch at the same time? We say “There!” We could say “Right there!” for even more emphasis, but in writing, less is usually more. “There!” seems to say everything in one syllable.

We could also ask to what the Tibetan ཐོག་ཏུ refers. It refers to what you are experiencing right at that moment. When you sit with your teacher and follow his or her instructions, when he or she asks you a question and your mind just stops, your teacher might say “There!” or indicate in some other way that you are experiencing what he or she is pointing to. There is a sense of immediacy in the Tibetan. According to the 20th-century Austrian-British philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, the meaning of a word is its use. If we follow his guidance, “There!” conveys the meaning at least as effectively as “directly.” Let’s try “There!” to translate ཐོག་ཏུ.

Now, what to do with “recognize”? Let’s go back to the actual experience of recognizing. Here it is not recognizing another person, but recognizing something about yourself, about what you are. Consider the situation when someone, a good friend perhaps, or someone you are getting to know, says, “Do you know that you are . . . ?” and she names some quality. It may be a compliment. It may be a criticism. It may be just an observation. At first you don’t see it. What is she referring to? She says it again or gives you an example. You still don’t see how that quality applies to you. And then you do. “Oh! Yes, I am that.” You recognize that quality in you.

That is what is happening here. A teacher, a fellow practitioner, a line in a book or a song, or a question from a student points you to a clear empty knowing that cannot be described in words, a knowing that does not rely on understanding or concept. You are a bit stunned at first; there is absolutely nothing there. But then you see. Underneath all the confusion of conceptual thinking and emotional reaction, underneath all the ideas you have about who and what you are, there is nothing—no self, not a vestige—but there is a clear empty knowing. There! This is what you are.

At this point, we could take a chance. Instead of trying to find another word for “recognize” that conveys that experience, why not go right to the experience? This is what you are. Recognition is implicit here, but that fits well with how the Tibetan original works. In Tibetan, grammar is centered more on what happens rather than who does what. Let’s take this for our first line.

There! This is what you are.

Interesting. Let’s keep going and see where this approach takes us.

The next line falls into place a little more easily. For some time now, I have been comparing mystical practice with musical practice. They are different, of course, but there is a lot of overlap in terms of the calling, the yearning, seeking out guidance, apprenticeship, training, experience, tribulations, struggles, transformation, accomplishment, and acquired skills. Many musicians pursue music at considerable cost to their health and well-being, they ignore or let go of alternative careers, and they may even neglect important relationships. They do so because they have to—nothing else matters. The same holds for mystics. Nothing else matters.

Nothing else matters? That phrase seems to capture the decisiveness of the second line better than “Decide on one point.” “Nothing else matters” conveys more than an intellectual decision. It carries emotional and experiential weight. Nothing else matters! And it does not contain any adverbs or any long words. It is a leap, of course, and it is definitely not a literal translation. However, we are going for clear meaning and experiential impact, not literal accuracy. And, perhaps fortuitously, the act of deciding now becomes implicit in this line, just as the act of recognizing became implicit in the first line. Let’s go with it.

There! Nothing else matters.

TWO DOWN, ONE TO GO.

The last line is the most difficult in Tibetan—so many ideas, so few words. We now have an additional challenge. At this point, we have

There! This is what you are.

There! Nothing else matters.

Both lines are six syllables. Wouldn’t it be great if we could find a way to put the third line into six syllables, too? In practice, that means five, because “There!” counts as one. Five syllables to express confidence, release, and continuing—definitely a challenge.

Perhaps we could get away with using trust instead of confidence? That would help with the syllable count. But what about release? What about continue? I could not find any shorter words that might work. I tried different formulations, including one that was a bit dubious grammatically: “Trust— let it unfold.” Still, I was not satisfied. Something was off.

At each step I have chosen clear meaning and experiential impact over literal accuracy.

Most teachers explain these three lines in terms of view, meditation, action, or, to translate them in another way, outlook, practice, and behavior. Outlook is the utter groundlessness of experience, that empty clarity that is our human heritage—this is what you are. Practice consists of coming to that again and again, whatever we are experiencing—nothing else matters. Behavior, how we live this, how we make it part of our lives, is based in the confidence of what we have already experienced—movement in mind releases itself, and this knowing is always present. If we let it, this knowing unfolds in every moment we experience. Mystically speaking, we make it part of our lives by having the confidence to step out of its way and just let it be. How do we say that in five syllables?

I am OK with “Let it unfold.” It isn’t literal, of course, but it seems to carry the idea of stepping out of the way and letting awareness be itself. The sticking point is the idea of trust or confidence. Ah! To keep the parallelism with the other two lines we should make the key idea implicit rather than explicit, and the key idea in this line is confidence. How do we make it implicit? I tried different ways, but nothing worked. Then, while I was listening to a flute duet played by a couple of friends in a bookstore in Sebastopol, California, it came to me:

There! Now let it unfold.

Why does “Now” work? I’m not quite sure, and it may not work for everyone. Perhaps it’s because it says (again implicitly) that you have come to this point and there is nothing to do but live in this awareness. To do that requires a great deal of confidence—confidence that mind, or mind nature, or natural awareness, functions just fine when it is freed from the fetters of conceptualization and reactivity. “Now” seems to say all that without saying it.

We are finished. The translation is complete, or, to be precise, we have taken it as far as I know how. As you see, at each step I have chosen clear meaning and experiential impact over literal accuracy. Does it work? The only way to know is for you to read it aloud and let it resonate in you. Then you will know whether it works or not. Here you are:

There! This is what you are.

There! Nothing else matters.

There! Now let it unfold.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.