Wild Wild Country

Directed by Maclain Way and Chapman Way

Duplass Brothers Production, 2018

USA, Six-part TV documentary series

All the strangers came today

And it looks as though they’re here to stay

—David Bowie, “Oh! You Pretty Things”

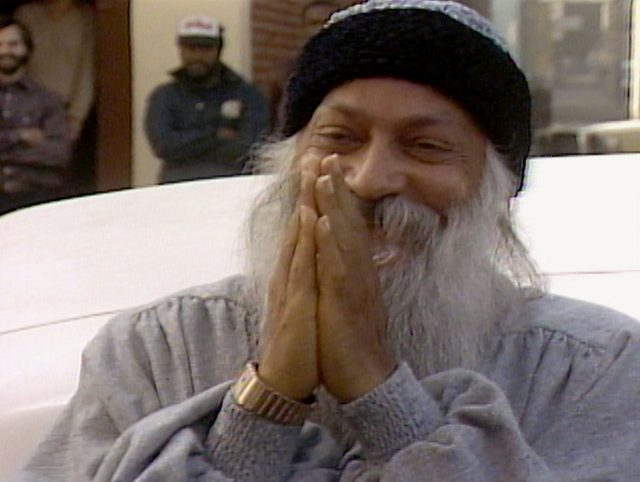

Maclain and Chapman Way’s film Wild Wild Country (WWC hereafter) is a larger-than-life documentary about Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh and his homemade paradise, Rajneeshpuram, developed by his followers in eastern Oregon in the early 1980s. I won’t rehearse the scandalous history of the commune; it’s enough for present purposes to say that it is full of deceit, betrayal, sex orgies (of course), assassination plots (surprisingly), bioterrorism (really surprisingly), and something close to civil war with the nativist Christians living down the road in the town of Antelope.

I’m also not much interested in extending the moral calculus concerning heroes and villains that has enflamed magazines, newspapers, and websites since the film’s release on Netflix in March. The media have been particularly fascinated by the character of Ma Anand Sheela, Bhagwan’s secretary and Rajneeshpuram’s primary administrator. Was she “evil,” as the prosecuting U.S. Attorney Robert Weaver insisted, or was she just protecting her people and their right to participate in a minority religion? Such questions are part of the sensationalism that has made the series so popular, but they shouldn’t be of primary interest here.

According to the Way brothers, the film began with a happy coincidence: they discovered three hundred hours of archival footage about the Rajneesh commune at the Oregon Historical Society while doing research for their first documentary, The Battered Bastards of Baseball, a charming and uncontroversial film about the Portland Mavericks, the last independent professional baseball team. The Way brothers had no prior interest in New Age spiritual movements or Human Potential; they were merely looking for product, their “next film.” And Netflix, for its part, was looking for “content,” something to help maintain the twenty million new streaming subscribers they gained in 2017. Baseball, Buddha: it was all the same to them.

What is notable is the fact that in this archive the Way brothers stumbled upon one of the first open conflicts in what would come to be known, in the 1990s, as culture war. Seeing this distant origin of the current antagonism between “bicoastal elites” and the “Trump base” is fascinating, like learning for the first time that the light that we see from a star has been traveling toward us for thousands of years. Disappointingly, the Way brothers don’t seem especially interested in how the Rajneesh conflict comments on the recent history of the culture wars.

Unfortunately, what they are interested in has more to do with “true crime” than social issues. For example, in the first episode of the series we are introduced to some of the good folk of Antelope. The surviving townsfolk are interviewed in their orderly and familiar homes, talking calmly and reasonably, full of good humor if not forgiveness. And yet their sense of once having been the victims of an outlandish group of religious crazies, perhaps a sex cult, remains strong. Their resentment for the “red people” (a reference to the colors in which Rajneesh’s disciples dressed) is still palpable, and their sense that they should “keep Oregon Oregon” (that is, keep it white and Christian) is still vivid for them, as is their fear of becoming a minority “in our own country.” Much to the Way brothers’ credit, it is captivating to watch as rural friendliness passes over to xenophobia, and then back again to reasonable concern, all in the course of a sentence or two, rather like people who, in principle, want to be kind but who often find that self-preservation makes it necessary to be cruel.

Following this introduction to local Oregonians, the Ways provide the first images of the sannyasins [devotees], the followers of Bhagwan. Ghostly figures dressed all in maroon wander in slow motion, aimless as zombies, down otherwise deserted streets. There is spooky, otherworldly music, perhaps meant to echo the soulless sound inside their heads. Members grin vacantly, and one plays the flute. From overhead, we see the beginnings of their massive “encampment,” as the CIA might put it, as if it were a photograph of a secret Soviet missile site taken from a U2. WWC may be a Netflix Original, but this introduction feels more like the History channel’s Ancient Aliens.

Moments later, the perception that there was something weird or demonic about the Rajneeshees is emphasized again by images of naked devotees writhing to heavy metal music, meditation as mosh pit, Black Sabbath stuff, real “worship this at your own risk” stuff. In other words, the visual rhetoric in these first scenes strongly suggests that the filmmakers are on board with the citizens of Antelope: strange doings! As Bill Murray says in Ghostbusters, “Human sacrifice, dogs and cats living together—mass hysteria!”

Of course, the Way brothers do not endorse bigotry, and they later allow the blunt-spoken Ma Anand Sheela to name it for what it is. But why then, if they aren’t xenophobic, would the Ways introduce us to the commune from such a morally canted angle? Are they trying to show us how the townsfolk perceived the Rajneeshees?

The answer is simpler than that: for the Way brothers, and implicitly Netflix, the weird intro is only a carny’s come on for you-the-viewer. It’s Dateline Oregon, a crime drama. The Way brothers are setting the narrative hook. The Rajneeshees are soon enough allowed to emerge from the alien haze in order to make their case, but, importantly, that case never wanders far from the scandals, the crimes, the lawsuits, and the bitter aftermath. It is only, if you will, what “Enquiring minds want to know.”

Unfortunately, this approach means that a lot of worthy questions don’t get asked. First, there is the question any decent police procedural should include: what did Bhagwan know about the criminal activities of his lieutenants and when did he know it? This one, you’d think, would be right in the Netflix wheelhouse. So in the course of the five days that the Ways spent talking with Sheela, why not ask?

There are other questions that don’t get asked. Shouldn’t any investigation of a religious group be curious about the group’s beliefs? In other words, shouldn’t the Ways have been curious about what exactly Bhagwan taught? He was obviously a very persuasive person. Thousands left their ordinary lives to follow him, and many thousands follow him still nearly 30 years after his death. It couldn’t only have been that beguiling smile and those depthless brown eyes, could it? There must be something in all the books he wrote. Well, what was it?

There is only one moment in the film when we learn something from Bhagwan, or from anyone, about his theology (if that’s the right word for it): he says that humans have two ways of dealing with sex. They can either repress sex or they can transform it. He was for transformation through creativity. He says, “Hence I teach my sannyasins to be creative. Create music, create poetry, create painting. . . . Bring something new into existence and your sex will be fulfilled on a higher plane.”

Obviously that is not an outrageous teaching. It is far less outrageous than the attitude of the Christians of Antelope whose anxiety about a “sex cult” made them like medieval inquisitors of Cathar heretics, who were persecuted for sexual deviance because they preached celibacy. In fact, Bhagwan’s eclectic teaching is nothing like the thinking of a sex cult: it is more like Freud’s theory of erotic libido transformed into creativity through sublimation. Rajneesh was a syncretist who crudely joined Nietzsche and Freud to the Buddha and the Bhagavad Gita and then threw in a little Dale Carnegie for the fun of it (Bhagwan was adamantly, even aggressively, pro-capitalist). It would have been useful to have someone explain that fact in the film.

The Ways have frankly acknowledged that they are not “very well versed in spirituality.” Worse yet, as Maclain Way explained in an interview with the movie review forum MovieBoozer, the brothers dislike documentaries “that have talking heads who have studied an issue for a really long time and have a PhD in something.” The Way brothers prefer “storytelling” to an academic setting of context. Given their candor, it is perhaps small-minded to suggest that their lack of spiritual “verse” disqualifies them from making a film about a spiritual movement, even if it is one as convoluted as Bhagwan’s. After all, in the Information Age—dominated by Wikis, blog sites, and chat rooms, all watched over by smarter-than-thou trolls—my information is as good as anyone else’s, even if I don’t actually know anything.

Ironically, it appears that Bhagwan felt much like the Ways. It does not appear that there was any coherent intellectual authority behind Rajneeshism beyond Rajneesh’s personal charisma, nor were there any institutional traditions. The only proof for his authority was how one “felt,” especially how one felt in his presence. Apparently, Bhagwan didn’t need any PhDs either.

What this suggests is that both the filmmakers and their subject worked within what the social critic George W. S. Trow called “the context of no context.” Both WWC and the religion it examines are ahistorical, and both lack an intellectual framework. Both are convinced that whatever they need can be summoned in the moment from their own idiosyncratic resources.

The downside of this approach is that the film comes almost wholly from perspectives that are self-interested. Whether listening to members of the commune, neighbors, or lawyers, one has to listen to their stories “across the grain,” that is, one has to listen skeptically and bring to the film the social, religious, and intellectual contexts that the film itself refuses to provide. That’s a tall order for most people, which is why the judicious use of experts, people outside the fray, is a good thing in documentary filmmaking. Deprived of that, WWC devolves toward mere infotainment.

Another outrageously absent question is this: what was daily life like for the typical sannyasin? To judge from the comments of the commune members at the end of the film, even after all of the uproar and scandal, a lot of them were very sad when the commune closed and they had to move on. There are reasons for that sadness. As Milt Ritter, a cameraman for a local television station, said in an interview at the news website Uproxx:

Look at what the Rajneeshees did in just a few short years with this ranch that was completely depleted of everything. It was so overgrazed and in such poor, poor shape. They turned it into an oasis. They planted tens of thousands, maybe hundreds of thousands of saplings along the creeks. They replenished the riparian zones, and then they built that big dam and all those buildings. Some of them were not small buildings. It is amazing what they did. The organic farms, the meeting areas—it really is amazing what they did in such a short period of time.

The absence of any portrait of the daily experience of the commune caused Sunny Massad (formerly sannyasin Ma Prem Sunshine) to complain to Rolling Stone, “I believed that he [Maclain Way] genuinely was going to do a story about the people that lived in the community—not just the few people who destroyed it.”

If the leaders of Rajneeshpuram were involved in a “criminal conspiracy,” as federal attorneys proved in court, it plainly was not a conspiracy for everyone involved. Some of the people who lived there were guilty only of wanting Rajneeshism to be a real response to their own longing for something other than a brutal status quo that has only gotten more brutal since then (more debt, more soulless work, less education, more inequality).

The most articulate and persuasive spokesperson for those folks is Bhagwan’s attorney, Philip J. Toelkes (Swami Prem Niran). His story is compelling: before the commune he was “burnt toast,” a corporate lawyer, but in the commune he was “loved and accepted . . . for the first time.” Toelkes is admirable not because of his loyalty to Bhagwan and his cult, but because of his loyalty to his own experience. For the film’s audience, Toelkes’s testimony is dissonant: we feel that his loyalty to Rajneesh’s cult of personality is mistaken, but we can’t dismiss his claim that the community he discovered in the puram changed his life for the better.

This dissonance should have led to the biggest question, the opportune question that WWC seems willfully to ignore: “Why do people seek out cultures that are a negation of the culture into which they were born?” And this one: “Are such cultures viable alternatives for the future?” The dominant narrative in mainstream discourse is that the ’60s are dead, the counterculture failed, and communes always end in disappointment and tragedy. Because WWC presents Rajneeshpuram primarily as a disaster, it only contributes to the widely received idea that communes shouldn’t be attempted, are doomed to failure, are cons, and so forth.

This narrative presents itself as accepted wisdom even though it flies almost entirely in the face of the fact that every major aspect of the social turn that we know as the ’60s counterculture is a living part of the present: anti-capitalism, feminism, gender equality, ethnic/racial equality, environmentalism, food and housing cooperatives, and—relevantly—alternative spiritual traditions, especially the ever-enlarging Western Buddhist community. San Francisco’s Zen Center has had its share of scandals and challenges, but would a documentary similar to WWC do justice to its work and legacy? In spite of those scandals, Buddhist sanghas, meditation centers, and countercultures of whatever other stripe should continue to try to offer what Attorney Toelkes was so grateful to find at Rajneeshpuram: love, acceptance, and an alternative to the corporate sociality of money. As the Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek has said of the Russian Revolution, they should continue to try, and if they fail again, we can only hope that they fail better.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.