There were salmon here once, in Montana, before a deep change occurred. There is still the alchemy of leaping, gleaming wild trout in Montana, but I believe there used to be salmon—oceangoing salmon. It’s a little-known fact, yet one that anyone who’s interested in exploring the history of the garden could discover.

There are texts that predate ours.

In certain forests, far up in the mountains, where the little creeks rush wild as they emerge from their dramatic headwaters, there are a few boulders that bear the etchings of the first humans who were here, perhaps back before the ice closed in and collapsed over the rivers in temporary dams. The petroglyphs show men in the river netting enormous fish—salmon—in the midst of wild rivers where salmon were never known to exist. As if back then a secret passage to the sea existed.

You have to know where to look, to find those few boulders, or be lucky. You might stumble upon one once in a great while, lost in the woods. There aren’t many, and for the most part, lichens have swarmed over them, obscuring the art. Only the occasional wildfire that burns all the way to water’s edge—burning, against all odds, through the wet cedar and aspen and birch along the river— scours the lichens briefly, making it look, in that moment, as if the rocks themselves are burning, though the window for viewing such smoking, gleaming, newly-bald texts is always very narrow; in half a hundred years the texts will be speckled with lichens again, the story hidden once more, until the next burning.

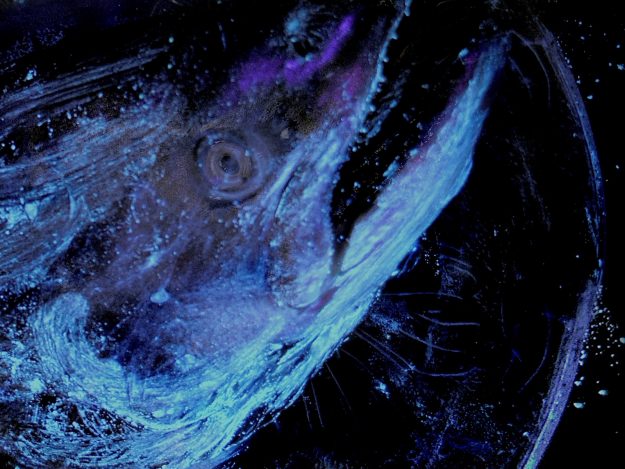

There are still pockets of these little-known ghost salmon, here and there, still alive, and crafted to a different species—the inland redband trout—hidden in Montana. They are living ghosts from a time when all rivers were wild. Cut off from the ocean, the magnificent once-upon-a-time seagoing salmon became landlocked. They adapted, though in so doing, they had to give up much that was great and even mythic, in order to simply survive. Trapped in the high lakes, as they waited for the ice dams to melt, they were forced to become something new, something smaller.

There were salmon in Montana, and not so long ago, before they were walled off. If you core the depths of giant cedar trees, you’ll find marine nitrogen in them. The only way that marine nitrogen could have gotten here was in the protein of salmon. The grizzly bears would have feasted on them back then and deposited the protein, with its signature of the sea, there in the cedar forests.

What happened? Who closed the gate on them, and why? Will they be back, and when?

To survive in their newer environment, the landlocked salmon had to become smaller, shrinking in size each generation, nibbling at the edges of life—nipping at dusk-delicate high-elevation summer mayflies—instead of biting off huge chunks of life. Their coloration changed from oceangoing silver to the red-and-green mottling of the stones on the bottoms of the high mountain lakes, so that they blended in, becoming not just tiny but invisible in their stubborn survival. But surely they remain haunted by the memories of when they were once great and free; and surely they were most haunted in the late summer, when the old echoes of who they once were called to them most strongly.

Perhaps they waited—and still wait—for those narrow slots in the mountains to open up once more. Even the most slender gap or cleft between two peaks, the narrowest passageway, could get them there now; the slightest tilt of earth, the smallest bulge, changing the flow of things.

In the meantime, no longer able to access the passages by which they got here, they marched their slow, beautiful way toward extinction, with the irreducible thing in them, the little gemstone of their ever-swirling genetic signature, becoming so small as to resemble one little dot of white fire in the cold, vast universe.

Such small, small fish, compared with what they once were, and becoming even smaller.

So there are salmon in our trees, and salmon on our rocks, hidden for centuries at a time beneath the history of our lichens. We do not want ghost salmon, but they are here, beneath our feet and in the air, in the smoke of the cedar we burn in winter, and in the smoke of the cleansing wildfires each summer. We must live with those ghosts, and, as ghosts do, they both haunt and sustain us. Those salmon vanished slowly, gracefully, over deep geological time, while all around us so many other species are disappearing now with the seeming speed of a light being turned off.

I know which rate of change I prefer. One is elegant, the other awkward and ill-fitted to the world’s older rhythms. I am not graceful, which may well be why I am so alarmed by the gracelessness of the sudden leavetaking of others.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.