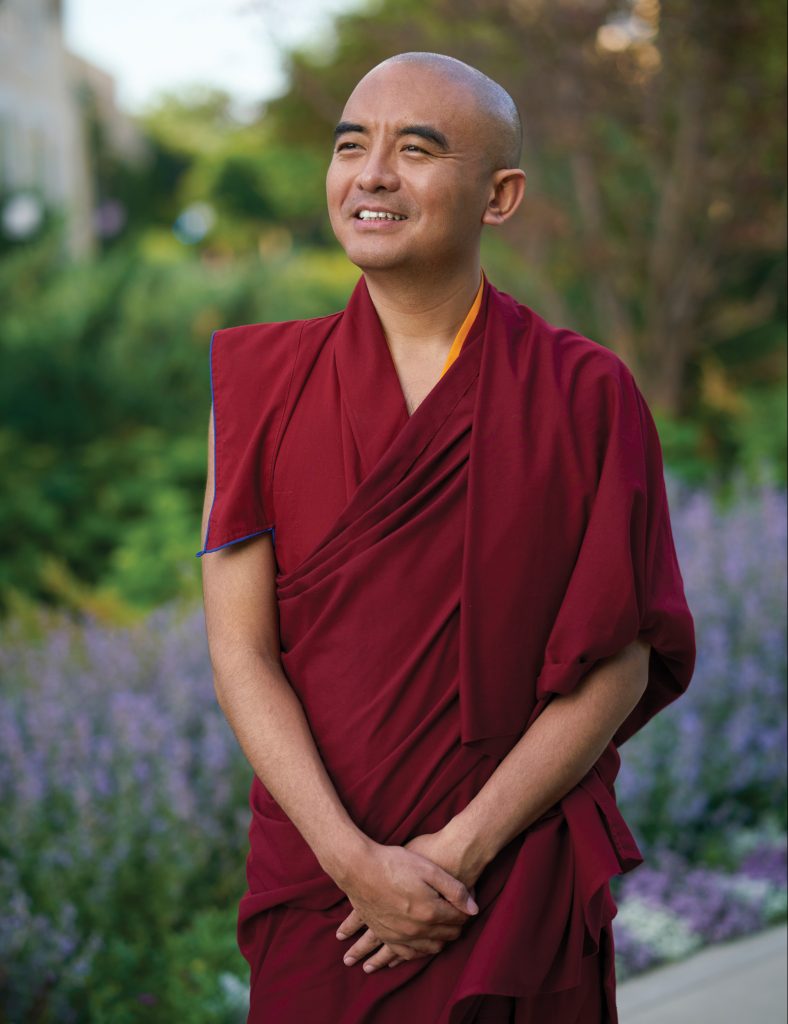

In June 2011, the abbot of Tergar Monastery in Bodhgaya, India, Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche, snuck out of his own monastery, leaving behind a letter explaining his intention to do a wandering retreat for the next several years—to beg for alms and sleep on village streets and in mountain caves.

The youngest son of the esteemed Tibetan Buddhist meditation master Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche and a world-known teacher in his own right, Mingyur Rinpoche explains in his new book, In Love with the World: A Monk’s Journey through the Bardos of Living and Dying, that he aspired to shed the protections and privileges he had enjoyed his whole life and to let go of his outer identities in order to explore a deeper experience of being. He was away for four and a half years, returning in the fall of 2015.

Watch “Letting My Self Die,” Helen Tworkov and Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche’s discussion about what the bardos can teach us about letting go.

Mingyur Rinpoche left his monastery with enough money to purchase the saffron shawls worn by homeless sadhus [religious ascetics]. But for the first two weeks of his wandering retreat, he carried these in his knapsack, continuing to wear his Tibetan robes and paying for lodgings and food. In this excerpt, he is in Kushinagar, the town where the historical Buddha died. Pilgrims come here to visit both the Parinirvana Park, which commemorates the place where the Buddha died, and the nearby stupa that marks the place where the Buddha was cremated. His money is running out, and he is just about to make the transition to living outdoors and begging for food.

***

Each evening in the guesthouse, I wrapped the sadhu shawls around my body, just to try them out. There was no mirror and little space to walk, and at first I wrapped the dhoti around my legs so tightly that I could barely move. Eventually I figured out how to bunch up the material in the front, which allows the legs to move easily. Then I took them off, folded them, and returned them to my backpack. Not wearing Buddhist robes was still disturbing.

I had received my first robes from the great master Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche when I was four or five years old, and have worn robes since that time. Monastic robes help shelter the mind from straying into wrong views or incorrect behavior. They offer a constant reminder to stay here, stay aware. They reinforce the discipline of the vinaya vows—the rules that govern Buddhist nuns and monks. I wasn’t too concerned with behavior, but rather with the discipline of maintaining the recognition of awareness amid new chaotic environments. My discipline had been safeguarded by robes. I would lose my main public prop. The closer the time came to removing the robes, the more they felt like an infant’s blanket. Without them I would be naked and vulnerable, a babe in the woods, abandoned to sink or swim on my own. Then again . . . I reminded myself . . . this is what I signed up for. This is why I’m here—to abandon the robes, let go of the self who is attached to robes, to live without props, to be naked, to know naked awareness.

I looked around the room as a farewell gesture. Goodbye to my life in Buddhist robes. Goodbye to sleeping where I belonged.

I used the last of my money to pay for one more night at the guesthouse. The next morning, I folded my maroon robes and sleeveless yellow shirt with the mandarin collar and little gold buttons that look like bells, and placed these cherished items in my backpack. I wrapped the cotton orange dhoti around my lower body. The cold showers with no soap had been enough to leave my body feeling cleansed, but it had been more than two weeks since I had last shaved. My beard and hair had grown out quickly, creating sensations around my face and neck that I had never known before. I looked around the room as a farewell gesture. Goodbye to my life in Buddhist robes. Goodbye to sleeping where I belonged—even if belonging was a superficial transaction secured with two hundred rupees a night. No more private dwellings—except maybe in a cave; mostly streets, and groves, and forest floors. No more paying for food or lodgings—the true beginning of making the whole world my home.

I looked around the room one last time, and then I left, taking short steps and deep breaths. At the reception area, I told the proprietor that I would not be returning. I had anticipated that he would ask about my outfit, but all he said was, Your robes are very nice. I thanked him.

Finally. No Tibetan robes. I felt like a branch that had been cut from the trunk, still oozing sap from the fresh wound. The trunk of my lineage would be fine without me. I was not sure that I would be fine without it. Still, there was a pervasive pleasure, even a thrill, in finally doing this. One step outside, however, and embarrassment pinned me in place. I became a saffron statue. The cotton was so thin that I could hold both shawls in the clasp of one hand. It was practically nothing. I felt nude. Never had so much air touched my skin in public. Body and mind were covered in shyness. The workers in the nearby restaurants and food stalls and the corn vendor who had seen me come and go these past days began to stare. Once again, it was too much too soon. New clothes, no robes, no money, no lodgings.

I must move, I told myself, and the shackles tightened. No one said anything. No one smiled. They just stared. I tried to affect a look of chilled-out detachment. Once my breathing calmed down and my heart stopped racing, I turned and began walking.

The disturbance was enough to break my awareness. I noticed this with no particular judgment. What a wonderful change from previous years, especially from when I was a young monk and suffered from frequent panic attacks. In the old days, I berated myself quite regularly for any discrepancies between some ideal version of practice and what I was actually able to do. If I can stay with awareness, great. If not, that’s okay too. Don’t create stories around good and bad, about how things should be. Remember: Shadows cannot be separated from light.

I had been meditating every day inside the Parinirvana Park, so by now the guards and I knew each other, and I was concerned that a saffron dhoti might arouse their suspicions, that they might wonder if I had committed some wrongful act that would make me want to hide behind a different identity. I walked to the Cremation Stupa, located within a guarded, gated park of its own. As I planned to spend the night there, I did not enter, but walked between the outside wall and a small stream, which is where the Buddha supposedly took his last bath. Now plastic bottles, bags, and wrappers line the banks. About halfway around, a small Hindu temple sat in a clearing. I chose a grove to the side of the clearing, near a public water pump. In my sadhu persona, even if I was noticed by the temple caretaker, my presence would cause no concern. I placed the folded lower skirt of my maroon monk’s robes on the ground for a sitting cushion. The area was still and quiet. By the time I arrived, a pack of mangy dogs had already settled in for a listless summer day of sleep, jerking awake only to scratch their fleas. Once I sat down in the shade and began my regular practice, the change in outfit had no impact.

At midday, I walked back to the restaurant that I had most often frequented, passing shops with large glass display windows. For the first time, I saw myself dressed as a sadhu. Who was this guy? He looked sort of familiar, and not. Now I could see how long and thick my beard had grown. I thought I could see some black insects near my shoulder, but it turned out to be wisps of hair. I had already lost some weight, but the greatest shock was to see myself out of Buddhist robes. Just as I had not known how reliant I had become on external forms of protection until I stepped into the world without them, I also had not imagined the degree to which I had identified with my robes until I experienced their absence.

The intention when meditating with emotion is to stay steady with every sensation, just as we might do with sound meditation. Just listening. No commentary.

As I drew closer to the restaurant, my breathing became markedly erratic. This was my first time begging, and I started to inhale as if trying to inflate my vocal cords with self-assurance. I had thought this through. I knew the drill— so to speak. But it’s not too hard to imagine eating whatever goes into your bowl when your attendant only serves your favorite foods. I had vowed to eat whatever I was given. I would not refuse an offering of meat if it was presented as alms; I would not starve to death to protect my own preferences. By now I was quite hungry. When I stepped into the restaurant I had been frequenting in the days prior, now wrapped in saffron, the waiters recognized me and—using a term of respect for an Indian holy man—called out, Babaji, Babaji, you are Hindu now!

Even with this jovial greeting and my many rehearsals, my blood froze. For the second time that day I stood still as a statue, my palms sweaty, my voice stifled, my mouth quivering. I wanted to run away. An interior voice goaded me on: Yes! You can do this! You must! But my body said, No! You can’t. The waiters began to stare. I had to force words from my mouth. My my . . . my . . . mon . . . ey . . . is finished, I stammered, can you please give me something to eat? The manager displayed neither surprise nor disdain and matter-of-factly told me to return to the kitchen door in the evening after they had served the paying customers. I had the impression that however momentous this request had been for me, he was an old hand at the begging business.

Related: Homelessness Into Home: On the Origins of Buddhist Monasticism

Just asking for food was a big step for me, even if the results were mixed. My request had not been totally refused. But it had not been granted either, leaving me feeling humiliated, and still hungry, and practically naked in a robe as sheer as mosquito netting. I navigated my way back to the stupa by way of the corn vendor. Seeing my change of outfit, he showed no sign of friendliness and refused my request. More discouraging news, but still I had asked; I had put another puncture in the fabric of old customs.

I returned to the grove near the Hindu temple. As my stomach gurgled from hunger, various emotions again surged, for I had taken the refusal of food personally. What craziness! I am working to take off the ego hats, to know that they are not real, to know that my monk’s role is not real, that my sadhu persona is not real—and yet some version of me just felt stung by not getting what I asked for. Who is this? Spoiled baby Mingyur Rinpoche? Esteemed abbot? What difference would that make? None. It is all gone. It is all emptiness, all delusion, the endless misperception of mistaking this collection of labels for a real and lasting self.

I had been doing an open awareness meditation. Essentially, all meditations work with awareness. The essence of meditation is recognizing and staying with awareness. If we lose our awareness, we are not meditating. Awareness is like a crystal or mirror that reflects different colors and angles: forms, sounds, and feelings are different aspects of awareness and exist within awareness. Or you might view awareness as a guesthouse. Every type of traveler passes through— sensations, emotions, everything. Every type is welcome. No exceptions. But sometimes a traveler causes a little trouble, and that one needs some special help. With the hunger pangs fueling feelings of vulnerability, shyness, rejection, self-pity, the guest whose name was embarrassment was asking for attention. Embarrassment might be subtler than anger, but its impact on the body can be almost as great.

The intention when meditating with emotion is to stay steady with every sensation, just as we might do with sound meditation. Just listening. No commentary. Resting the mind on the breath can turn breath into support for maintaining recognition of awareness, the same as with anger, rejection, and embarrassment. At first, I just tried to connect with embarrassment, which was the dominant feeling.

Where is this embarrassment, and how is it manifesting in the body? I felt the pressure of shyness at the top of my chest. If I had a mirror, I thought, my chest might look caved in—I was pushing my shoulders forward, and making my body smaller than it was, as if trying to hide from public sight.

The embarrassment weighed on my eyelids like stones that kept them lowered. I could feel it in the downward pull of the corners of my mouth. I could feel the resignation of it in the limpness of my hands. I could feel it behind my neck, pushing my head down. Down, down. The feeling of going down. In the past, whenever I was heavily embarrassed I wished to crawl down a hole. I did not have that image now, but the sensations echoed the same details: being lowered, becoming smaller, taking up less room, not feeling worthy of being on this earth.

At first, I felt resistance to these feelings, and I had to make resistance itself the object of my awareness. Then I could work more directly with the sensations in the body. I do not like these sensations. I started off feeling bad. And now, added to that, I feel bad about feeling bad.

Slowly I brought each sensation into the guesthouse of awareness. I let go of the resistance, let go of the negativity, and tried to just rest with feeling small, unloved, and unworthy. I brought these feelings into my mind— to the big mind of awareness, where they became small. The guesthouse-mind of awareness encompassed the feelings, the dejection, the bleakness, and became bigger than all of them together, dwarfing their impact, changing the relationship.

I continued doing this for several hours. I was starving, but I had become happy about feeling bad. Feeling bad was just another guest, another cloud. There was no reason to ask it to leave. My mind could now accept it, and from the acceptance, a distinct physical feeling of contentment pervaded my body.

Not much happens in Kushinagar on hot summer nights, and the restaurants close early. I had only drunk water for the whole day. At about seven o’clock, I walked back to the restaurant and stood at the kitchen door. The rice and dal that had been left on people’s plates had been scraped off into a pot that sat on a counter. No more choices. A waiter scooped some leftovers into a bowl for me. The rest would be fed to the dogs. I ate standing at the door—a more delicious meal than any I had eaten at five-star hotels.

I returned to the same grove along the outer wall of the Cremation Stupa. As the evening light faded, I rolled out my shawl and lay on my back. I could not quite believe it: my first night outside. Spending the last of my money had taken a toll. The lifeline that could have reeled me back to safety, to food and shelter, had been broken. I was now adrift. I could no longer afford to reject anything. Not the food I was given or the bed that I now had. I had begun this journey with preparations. Now I thought, This is the true beginning. Sleeping outside, alone, the ground for my bed, begging for food. I could die here and no one would know.

All my life I had been in the presence of others, but I had not recognized the cushioned depth of protection they provided. I had understood that it was the responsibility of certain individuals to take care of me. Now there was a more delicate sense of these bodies linked together—like a chain-link fence—to form an unbroken circular shield around me. I also saw that I had not fully appreciated how this protective shield had functioned until it was gone—there would be no more coat in wintertime, no parasol in summer.

Related: The Last Blissful Breath: A visit to Kushinagar

Despite my yearning to be self-sufficient, my first days after I left the monastery had showed me in a very primitive way that I had taken my life for granted. For the very first time ever, I had walked alone, talked only to myself, taken a train alone, ordered food and eaten alone, laughed alone. Feeling so isolated from my protectors had left me feeling flayed—stripped of my own skin, bereft of even a thin casing.

The absence of any protection had come into focus slowly. Although my daytime excursions in Kushinagar had been increasingly relaxed, I had still felt the undercurrents of embarrassment and vulnerability. Now, my first night outside, the undercurrents became more like riptides. I was seized by the full weight of solitude, the feeling of being very far from safety and utterly undefended.

I had taken this invisible shield for granted so completely that I had not been able to see it. It’s like taking air for granted—and then suddenly finding yourself in a room without oxygen. Oh, I get it, that’s the element that my life depends on. I had entered a strange land, an alien territory with alternative requirements. I longed for this world to feel hospitable, but it did not, and I could not find my footing. Stripped of my lifesaving element, without even knowing what that was, I had peered into darkness like a sailor trying to navigate his return home. I longed to leave behind this misfit, this fish out of water, who was not even suited to share a public park with rabid dogs. The ground does not accept my body. My shape is not right, my smell not nice. Nonetheless, I have given up choices and here I am.

It was the longest night of my life. The mosquitoes did not let me sleep for an instant. When I got up to pee, the dogs that had been indifferent during the day turned vicious. But between intense spells of disorientation, my mind continued to comment on the wondrous triumph of pulling off this plan, marveling at actually lying here, on my maroon sheet on the dirt ground near the public pump. Throughout the sleepless night I vacillated between distress and delight, and I welcomed the first hint of dawn.

♦

From In Love with the World: A Monk’s Journey Through the Bardos of Living and Dying, by Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche with Helen Tworkov © 2019. Reprinted with permission of Spiegel & Grau, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.