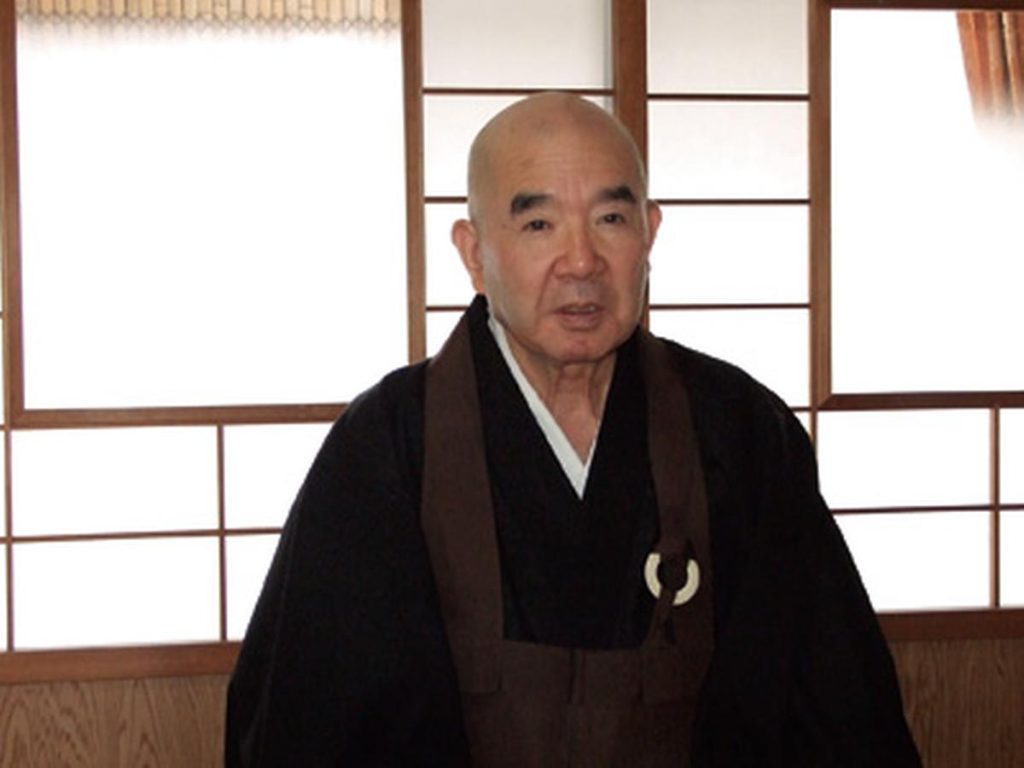

Harada Sekkei Roshi is a teacher in the Soto Zen tradition and abbot of Hosshinji monastery, in Fukui Prefecture, Japan. This past May, his student Keiko Kando spoke with him about the meaning and function of Zen. Harada Roshi’s book of dharma talks, The Essence of Zen, is to be reprinted by Wisdom Publications next February. This interview was translated from the Japanese by Heiko Narrog.

What do people search for in life? People are looking for liberation from their fears, worries, and anxieties; that is, for freedom from the bonds of birth, old age, sickness, and death. Even in our times—where mankind has developed this amazing modern civilization with scientific wonders—people still continue to lead their lives trying to figure out solutions to these fundamental matters.

What kind of solution does Buddhism offer? Buddhism has taught the dharma (the law, or the truth) by speaking about the theory of conditional causation. This means that since everything comes to life and ceases through causation, everything is without a center and nothing has real substance. Therefore, everything changes constantly (that is, everything is impermanent) and is without beginning and without end (that is, everything is without self). One cannot recognize any form in things. However, ordinary people mistakenly think that there is some real substance in things. As they cling to this delusion and run after it, various afflictions arise. These afflictions are ultimately all related to birth, old age, sickness, and death (the four sufferings).

Shakyamuni Buddha taught that all material things are subject to laws. Birth, old age, sickness, and death are laws in themselves, and not problems that have to be solved through the power of human beings or through some other power. On the contrary, giving oneself over to birth, old age, sickness, and death as they come is the way to liberation. There is no “good” and “bad” in laws. Only through the intervention of people’s views does this notion of “good” and “bad” arise.

What is Zen, then? In the Soto sect, it is taught that Zen itself is enlightenment. Zen is everything in daily life. There are people who think that sitting is the best way of practicing Zen and that everything else is secondary, but this is a grave mistake. Zen is becoming one with all truths. It is easy to be misled by the word “zazen” [Zen sitting meditation] and think that it refers to some special practice, but this is not the case. If the goal of all religious practice in the world is to become one with the truth, then this is all Zen. Ultimately, there is no way to peace of mind outside of Zen.

Why, then, is the form of zazen necessary? To answer this question, let us consider the example of Eihei Dogen, the founder of the Soto sect. It took Dogen Zenji an enormous amount of hardship and effort at Mount Tiantong in China under Master Rujing before he attained liberation. In his book Shobogenzo (Treasury of the True Dharma Eye), Dogen Zenji endeavored to explain the essence of the Buddhadharma as exhaustively and in as much detail as possible. Basically, however, he taught with a lot of repetition how to become familiar with oneself.

I will explain the book title word by word. Sho (true) means something that eternally doesn’t change. Ho (law of the dharma) is everything that appears before our eyes, that reaches our ears, and that is touched by our hands. Gen (eye) means literally the eye and simultaneously connotes the function of all six of our sense organs (eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, mind). An eyeball doesn’t judge anything as beautiful or ugly, it just reflects. Our ears, noses, and tongues are the same. All things arise as causes through the function of our ears, eyes, noses, tongues, and bodies, and the tool that makes judgments such as “I like it” or “I don’t like it” is called “mind” or “consciousness.” Zo (treasury) means that all our functions—suffering as suffering, fear as fear, distress as distress—are already liberated. All these taken together, Shobogenzo, means that we ourselves are the eye that sees everything truly as it is. The fastest way to affirm that we ourselves are the Treasury of the True Dharma Eye is to face a wall, cross our legs, and do zazen.

What methods are there in zazen? When one sits zazen, pain in the legs and various delusive thoughts arise. I therefore teach three methods: susokukan (counting the breath), zuisokukan (following the breath), and koan kufu (working with a koan). These are only temporary expedients for the sake of zazen, like a stick used to walk, and not ends in and of themselves. Susokukan is the Zen of silently counting “one, two, three . . .” until ten, and then returning to “one” again. Zuisokukan is the Zen of viewing one’s breath, becoming one with every out-breath and in-breath. And finally, koan kufu is the Zen of thinking about a problem to exhaustion, becoming one with problem consciousness, grinding down consciousness through consciousness. One can choose one of these three “sticks” and sit single-mindedly with it. This is zazen.

If you do this, can you indeed attain liberation from fear, worries, and anxieties, and freedom from the bonds of birth, old age, sickness, and death? The priest Wumen once wrote, “A hundred flowers blossom in spring, the moon shines in autumn, there is a fresh breeze in summer, and there is snow in winter. If your mind isn’t occupied with trivial matters, every time is a good time.” In this poem, everyday mind is described in terms of snow, the moon, and flowers. A world is expressed that doesn’t belong to intellect or to non-intellect, and where human thinking is of no use. There are flowers of delusion and flowers of enlightenment, flowers of exhilaration, anger, sadness, and joy.

The samadhi [nondual consciousness] of all these activities is like hundreds of flowers in full bloom; there is nothing to search for outside oneself. As the poem “A fresh breeze chases away the bright moon; the bright moon chases away the fresh breeze” expresses, the mind has stopped seeking. It has freed itself of the silliness of letting the precious gem held in one’s own hand slip away while longingly gazing at the moon far away in the sky. As the expression “If heart and mind are wiped out, fire itself becomes cool” tells us, there is nothing as refreshing as to forget oneself.

Wumen’s closing words mean “at that time a human being can truly be a human being, nothing to be worried about.” However, as Master Zhaozhou told his disciples, “There is no better thing than no thing.” That is, no matter how wonderful something is, there is nothing more wonderful than no thing. These words very accurately express the ultimate point of practice and the austere and impermanent beauty of human life.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.