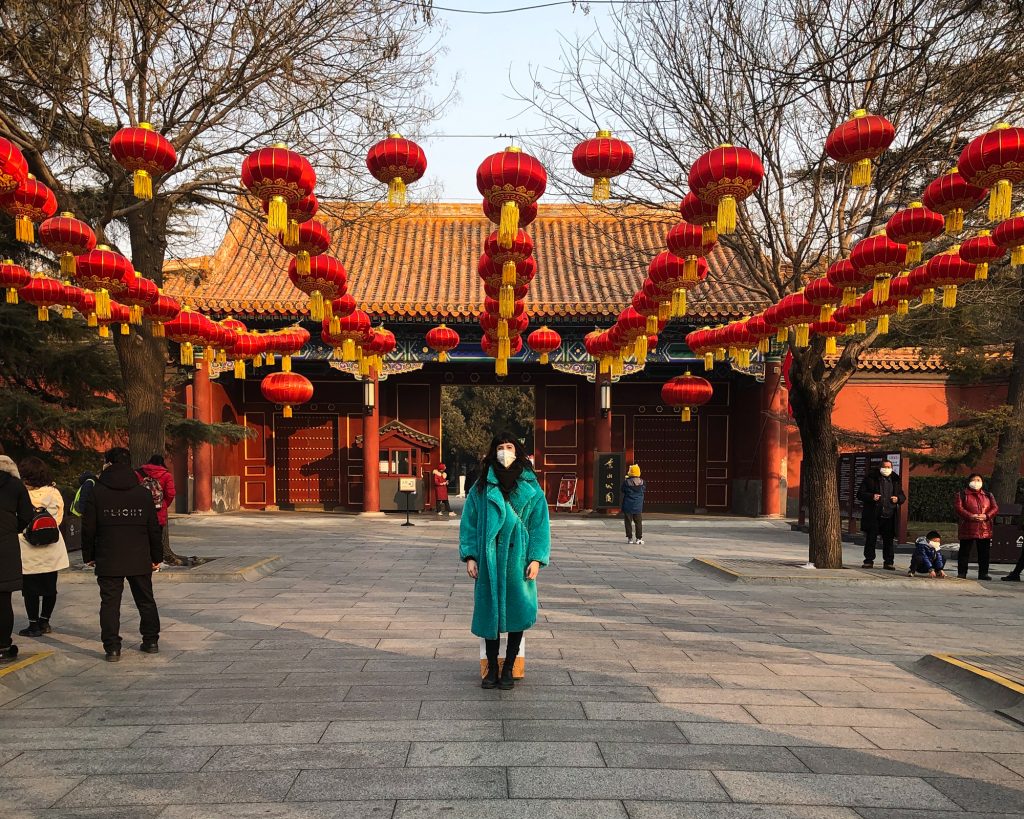

I flew to Beijing on January 18, four days before international news outlets began reporting on the coronavirus outbreak, now a global health emergency. Our small group had been planning our big adventure since the summertime, excited to visit a mutual friend of ours who had been studying in China for the last several months.

From Beijing, we went immediately to Harbin, a city in northern China famous for their seasonal ice and snow sculptures. We spent our first few days there cavorting in subzero temperatures, taking silly pictures with giant snowmen and climbing the neon-lit walls of the festival’s life-sized ice castles. We started to hear talk about a virus down in Wuhan—over a thousand miles away—but the people we spoke to were unconcerned. “The virus?” said the day-trip coordinator working at our hotel. “That’s in Wuhan. Not here.”

Then, on January 22, China took the unprecedented step of sealing off Wuhan, and global news coverage of the coronavirus exploded. Circumstances changed literally overnight. When we woke up on January 23, instead of breezily brushing away the virus talk, the hotel’s front desk person stopped us on our way out to breakfast. “You have to wear these now,” she said, handing us four black face masks.

We returned to Beijing and then flew to Chengdu as we had planned, now glued to the news. The New Year’s festivities were canceled. The panda base center was closed. We weren’t allowed to visit the nearby mountains; there were police checkpoints, we were told, and no one wanted to drive us, anyway, even for double the price. We spent two days wandering around what felt like a ghost town before changing our flights and going home early, right before American airlines began suspending their US–China routes.

Even in Beijing and Chengdu, each over 700 miles from Wuhan, and surrounded by an obedient, face mask-wearing public, we had all succumbed to coronavirus anxiety. Was my minor sore throat from all the travel and our go-go-go itinerary, or was it the first signs of the virus? Was my friend’s morning cough from the cold she had a couple weeks ago, or were we all infected? It was worst for my friend currently living in China, whose school at first told her that the spring semester would be postponed by two weeks. Three days later, it had been canceled entirely, and she was faced with the decision of packing up her entire life or waiting out the outbreak isolated in her Beijing apartment. Friends and family were emailing, texting, and reaching out on social media. “Come home.”

And then we did. Our temperatures were checked before we were allowed into the Chengdu airport. During our layover in Shanghai, we filled out forms declaring that we had not been to Wuhan and were symptom-free, and handed them to officials wearing Hazmat suits. Everyone wore masks, including during the entirety of our 14-hour flight to Atlanta.

Coming into the US, customs agents asked us merely if we had been to Wuhan. (I overheard one asking another passenger if he had visited “Wutang.”) The New York City’s Health Department announced that those who had recently been to China—even to Wuhan—did not need to self-quarantine as long as they were asymptomatic, which we all were. Still, one of my friends quarantined herself in her apartment for days, staying home from work and leaving only for necessities. I myself tried it for two before thinking that self-isolation was a greater danger to my mental health than me being outside was to the general public. I had a terrible case of jetlag, which meant I was compulsively checking my temperature at 3:00 in the morning. It never went over 98.3 degrees, but I kept worrying.

I’m beginning to see the first noble truth as itself a practice of compassion, an actionable choice—an opening to, a turning toward, a holding of.

These are the facts. There were almost 6,000 reported coronavirus cases on the day we left China, including 80 in Beijing, the biggest metropolis we had spent time in, according to China’s National Health Commission. In a country of almost 1.5 billion people, that’s around .0004% of an affected population. The percent infected in Beijing at that time was .00037%. At my closest to Wuhan, I was the equivalent distance of New York City to Charleston, South Carolina. I had worn a face mask 100 percent of the time in public—as did virtually everyone we saw—since the 23rd. The odds that I had caught the coronavirus were . . . slim to say the least.

But it wasn’t just me whose mind had been taken on a ride. I was supposed to celebrate my sister’s birthday shortly after my arrival home, but a close family member refused to see me until the possible 14-day incubation period was over. After I was invited to a Super Bowl party that Sunday, the host called an infectious disease specialist on the down-low about whether it was safe for me to come. (She said it was.) I attended, but left after less than an hour when someone commented that I was irresponsibly exposing them all to a deadly virus. I was informed intermittently by friends and others that the face mask I wore likely didn’t work or that I was stupid for going to a country “like China.”

While those around me worried I might pass them a sickness that I had little chance of having in the first place, 8,000–20,000 people died of influenza in the US. I felt a powerful empathy for those truly suffering from the virus, one sharpened by a shared reality that in all likelihood we didn’t actually share. I had had the barest of contact with the specter of the coronavirus, but could palpably feel the shutting down of people’s hearts around me. There was little concern about my own safety; the worry was expressed about their own skins. What could it be like for the sick in Wuhan and elsewhere? I wished fervently that their experiences have been and will be the opposite of mine—that they would be surrounded by fearless, open, loving care—but I knew this couldn’t possibly be true.

When I was in China, I was amazed to see how quickly an entire country shut down. I suppose it is just that easy, more of a non-action than something being done. Don’t show up at work. Don’t attend school. Don’t go anywhere, don’t do anything. Still, it was astonishing to one day see the hustle and bustle of a normally functioning city, and the next have all that activity cease at once, as if magicked away.

I am now also amazed at how quickly and easily we can shut down the kindest, most understanding parts of ourselves, when we are scared. That, too, I suppose, is so habitual that it is a kind of non-action, more reflex than choice.

A day after the awkward Super Bowl fracas, the host called me to apologize. It was a sweet gesture, and appreciated. “It wasn’t personal,” she said. “Unfortunately you just ended up in the middle of it all.”

“If we don’t want to get sick, then we should not be born in samsara,” wrote the Buddhist nun Thubten Chodron in 2006. Getting ill is part and parcel of the Buddha’s first noble truth. We’re all in the middle of it all, all of the time.

I had always considered this truth simply a description of reality, a jumping-off point for practice. Because of X, we do Y. But another understanding of it is as a response mechanism that dilutes the mind of fear and opens our hearts back up when they start to shut down. I’m beginning to see the first noble truth as itself a practice of compassion, an actionable choice—an opening to, a turning toward, a holding of.

Since I’ve been home, I’ve not necessarily been hiding from news about the coronavirus, but I’ve been reading it like someone trying to get through a chore as quickly as possible. It has been making me anxious to see the number of infected keep jumping daily, the media’s maps of the virus’ spread grow darker red. I understood perfectly the mindset that has led to panic even in the States, and in those immediately around me. How could I not? I was just like them. Opening my heart to those actually bearing the consequences of this outbreak wouldn’t greaten or lessen my chances of bearing them, too. Still, I keep turning away from the front pages and phone alerts, even while I grow increasingly grateful to the people in my life who have welcomed me back from China with solicitude, thoughtfulness, and grace.

The Buddha knew—disease crops up. There is suffering great and small. We adapt, or we don’t. Threats grow larger or shrink into the rear view mirror. We’re caught in Wuhan, or we aren’t. We catch the coronavirus or something else. We die, or we recover. None of us are immune from this reality. It’s what we do with it that makes the difference.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.