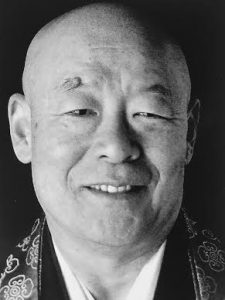

Eido Tai Shimano Roshi died on February 18 at the age of 85. He was in the first wave of Japanese Buddhist teachers who introduced Zen to America in the 1950s and 60s, having arrived in Hawaii in 1960, then settling in New York City in 1965. Eido, who was still Sensei Tai Shimano at the time, was installed as resident teacher of the Zen Studies Society (ZSS), founded in 1956. Eventually, he became abbot of two centers—Shobo-ji in Manhattan and Dai Bosatsu Monastery in the Catskills. It was a post he held until forced to retire in 2010 under charges of sexual misconduct.

I started sitting at Shobi-ji in 1978. I knew nothing about Eido Roshi or Zen but was desperate to find a meditation practice as a way to calm down; conveniently, the zendo was a block from my apartment. Peter Matthiessen’s book The Snow Leopard was published around the same time. Reading it, I “got” that his search for the elusive Himalayan cat was a quest for awakening, which made Zen practice all the more attractive to me. I knew that Eido Roshi had been Matthiessen’s teacher at one point, and I figured that anyone good enough for Peter Matthiessen was good enough for me. Only after I had been sitting at Shobo-ji for a while was I aware that Matthiessen had been in a wave of students who had left in protest because Eido was ostensibly hitting on women in the sangha [community].

I was among about five or six new students who took refuge from Eido and became members of ZSS in 1979. Though talk of the roshi’s sexual misbehavior was whispered around the zendo, I ignored it. As long as he doesn’t hit on me, it won’t be a problem, I insisted, arguing that my allegiance was to the teachings, not to the teacher. I came to regret that denial a few years later, after I’d completed a kessei, a formal 100-day training period, at Dai Bosatsu. Eido never made a pass at me, but I heard complaints from others. When in 1981, he banned women from Dai Bosatsu, arguing that we were temptresses causing all the problems with the monks, I got that the problem was Eido and parted ways with him and ZSS.

Though I valued the rigorous Rinzai Zen practice I had received, once I moved on, I put Eido Roshi in the past. But in 2010, when he was dismissed by the Zen Studies board amid accusations of sexual misconduct, I thought back 30 years and wasn’t surprised. By 2014, when Mark Oppenheimer’s inflammatory exposé of Eido Roshi appeared in The New York Times, the sexual predation of Zen masters and other spiritual teachers of note was widely known.

Still, in the days before #MeToo, public declarations of abuse by Buddhist teachers was unusual, and the issue was hotly debated. Was it only the teachers who were at fault? Did the women in question bear any responsibility? Should these incidents be dismissed as sexual peccadilloes, or were they, in fact, serious crimes?

It was often argued that for Asian teachers who had been sequestered in monasteries before coming to the West, sexual misconduct was an understandable response to the relaxed sexual norms here and the casually flirtatious behavior of American women. And weren’t some of these master-student encounters consensual? Blaming the victim—long an impediment to rape prosecution in the US—was invoked to fortify denial not only by the teachers themselves but also by the senior students running meditation centers, who were reluctant to censure their teachers. Few of the students wanted to admit that the master to whom they had pledged devotion was a sexual predator underneath his robes. Certain women teachers simply distanced themselves from their mentors rather than openly confront the issue.

All that has changed. But it’s hard even today to blame all the misconduct on the teachers. Sexual mores in the ’70s and early ’80s, pre-AIDS epidemic, were considerably more fluid. But given the asymmetry of power between student and teacher, a line must be drawn. Ethics is one of the three foundational principles on the Buddha’s eightfold path, but Buddhist teachers have no quasi-legally binding code of conduct like that to which most psychotherapists in the US are pledged to adhere. And then buried somewhere under all the controversy is the confounding matter of love. Since the beginning of time, love has subverted all manner of codes and norms.

Eido Roshi’s death, along with those of Joshu Sasaki Roshi and Taizan Maezumi Roshi before him, brings to an end the generation of Japanese-born Zen masters who introduced Americans to Zen. Demonizing these teachers for their sexual misbehavior disregards their worthy contributions. I liked both Eido Roshi and Maezumi Roshi. They were smart and compassionate, with humor and warmth, and imparted valuable lessons about Zen practice. Eido leaves a number of grateful students around the world. At the same time, it’s impossible to minimize the pain of the women whose trust he abused. I once worked in the Sex Crimes unit of the Manhattan District Attorney’s office and saw clearly that blaming the victim can be as shattering as the crime itself.

Eido and Sasaki and Maezumi are not the only Asian spiritual teachers to have fallen from grace as a result of sex. The Jain teacher Gurudev Shree Chitrabanhu and Yogi Amrit Desai are among them as well. And Western-born Buddhist teachers like Richard Baker Roshi have been openly censured, while accusations continue to circulate around a few others.

As charges of sexual harassment mount in the culture at large, with serious consequences for the perpetrators, Buddhist practitioners have their own gardens to tend. It is up to this new generation of students, women and men alike, not only to bring teachers to account but also to make sure their own behavior is above reproach. It isn’t just the teachers who need to zip up. The Buddha foresaw the problems sex could cause among householders as well as monastics, and he gave us the precepts for guidance. We have to be scrupulous in following them—in this case the third precept about refraining from causing harm in our sexual relations.

The lessons of the past also remind us that we need to be very careful in minding other people’s business. Transforming our own desire can be challenging enough.

Correction: An earlier version of this story included a headline that incorrectly identified Eido Tai Shimano Roshi as a Soto Zen teacher. He practiced in the Rinzai tradition. We apologize for the error.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.