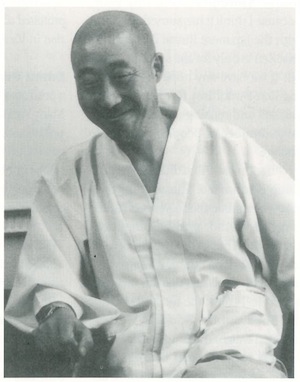

Venerable Samu Sunim became an orphan in Korea at the age of 10, after which he lived as a beggar on the streets of Seoul. One day, seeing a beautiful temple at the end of an alleyway, he went to inquire how he might live in such a place. The resident monk told him that he could do so only if he became a Buddhist monk, and so he traveled to a mountain monastery, where he studied in the Son (Zen) tradition.

Samu Sunim came to the United States in 1967. Since then he has established centers in Toronto, Mexico City, Ann Arbor, and Chicago. The following interview was conducted in New York last June by Tricycle Senior Editor Clark Strand.

You have been quoted as saying that it would take nothing short of a complete transformation of the Asian model of Buddhist monasticism for Buddhism to successfully establish itself in the West. What kind of transformation do you envision? We Buddhist teachers—those of us who came from Asia—are like transplanted lotuses. Many of us are refugees. Here we find ourselves in the marketplace—as dharma peddlers, you might say. I am concerned with the Zen movement becoming more easily accessible to ordinary common people.

You have said before that you feel that Zen Buddhism has been mostly an intellectual movement in America. It was largely the intellectuals who were attracted to Zen Buddhism in the beginning. Even today most Zen Buddhists are college-educated, liberal-minded—they’re mostly white baby-boomers who couldn’t make it back to their own childhood religions. We have failed to attract people from African-American communities. And we also have this attitude: if you cannot sit properly on the mat and cushion, then you cannot practice Zen meditation. That’s not very inclusive.

What accounts for these attitudes? It’s a touchy issue, because I think it has something to do with the Japanese Rinzai Zen attitude that Zen is only for the spiritually gifted. If we have any hope of establishing Zen Buddhism firmly on American soil and making it accessible to a large number of people, that has to change.

In monastic Buddhism, the main thing is to imitate Shakyamuni Buddha—to imitate the six years of ascetic practice he did after he renounced the world. That’s the whole monastic career. But I don’t think we can repeat that here, and there is no need to repeat it. I think the focus should be on Shakyamuni Buddha after he attained enlightenment. The first thing he said was, “Lo and behold, every being, without exception, without discrimination, is endowed with the Buddha-nature.” We ought to imitate what Buddha did for the last forty-five years of his life: ministry Buddhism.

So, the post-enlightenment Buddha is a better model for Buddhism? Yes. And that’s why monastic Buddhism in Asia is in such big trouble—for instance, in the case of Myanmar (Burma). A few years back, when the students took to the streets in protest of the military dictatorship, some young Burmese monks joined the students’ demonstrations; but the sangha, the elders of the Buddhist monastic hierarchy in Myanmar not only actively discouraged the young monks, they didn’t even have the courage to say anything to the military.

Perhaps that’s true, but what about the Buddhist monks who have protested all sorts of injustice and repression in Vietnam? Thich Nhat Hanh is a product of that generation of monks. Many Vietnamese monks have become politicized. So if you talk to them, you get a different feeling. They are not sleepy monks. They are very much more heightened in their awareness of social issues.

Do the conservative monastic traditions of Asia have too much interest in preserving the status quo? It’s just the old habit of looking inward. The old ideal was, first you look inside, and then reach out. But Asian monastics have been too preoccupied with looking inward, and they have failed miserably to reach out when the need was there in their own societies.

Everyone knows what has been going on in Tibet under Chinese military occupation, but so far I have not seen any Chinese Buddhist leaders come forward and condemn what the Chinese government has been doing in Tibet.

People in the West come from traditions that in many cases have a long history of social services and social action. When these students encounter teachers who speak of “engaged” Buddhism, they sometimes respond by saying things such as, “I should’ve just stayed a Catholic, because they have been doing it longer, and they do it better.” What would you say in response to that? Right now, Buddhism in the West is helping people who can come to Zen centers or Buddhist groups—people who can help themselves. We lack the organization, the funds, and the manpower to provide other kinds of aid. The Christian organizations are doing marvelous work. If there is an earthquake, they rush and help out. So far, I don’t think any of our Western Buddhist organizations are equipped to do that. But that does not necessarily mean that Buddhist groups in the West are not doing anything. Meditation training helps to reduce greed and remove anger and hatred. Thus we learn to become wise and not do stupid things. This is not less important than rushing out to help in earthquake zones. If you become a peaceful being, and if you have a compassionate heart, then your community, and your family can benefit greatly.

And yet you claim that Asian Buddhism is too stagnant, too concerned with the inner world of meditation. Well, we need to talk about a balance. Frankly, I think Asian monastics probably spend too much time sitting in meditation looking inward, and not enough time outdoors. They have to go out, as Shakyamuni did, and find out how people are living in society. But in the West, it’s the opposite problem. People spend all their time in the outer world. They’ve been successful in business, in their professional lives, but they have no relief from the stress of their lives. They need to sit down and settle the body and mind, instead of always running around feeling agitated inside.

So as an Asian teacher in America you have to go to the marketplace, because that’s where Americans are? That’s right. Buddhism in the West is out in the marketplace. And that’s what I say to people who are concerned with such things as scandals. If you place yourself in the marketplace, you have to be a little bit tainted to work with the people. And, of course, people make mistakes. People should not be afraid of making mistakes, but you have to be willing to learn from them.

Can monasticism survive in that kind of atmosphere? I think we have to talk in terms of high Buddhism and “folk” Buddhism. I think we need both. When I say high Buddhism, I mean monastic Buddhism; I mean monks and nuns living a protected life in a monastery so that they can devote themselves entirely to spiritual cultivation in order to ensure dharma transmission. But we need what I would call folk Buddhism as well—people who go out, as bodhisattvas, into the marketplace, actively involving themselves with people. Those of us who are doing high Buddhism have to understand that we are not the only ones who are capable of transmitting the dharma. We have to understand the transmission of Buddha-dharma in a wider sense.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.