It is like a person up in a tree hanging from a branch by their teeth. Their hands can’t grasp any limb and their feet can’t touch any bough. From below, someone asks, “Why did Bodhidharma come from the West?” If they don’t answer, they are avoiding the question. If they do answer, they fall to their deaths. At that moment, how would you respond?

–The Gateless Barrier, case 5

I

Around 9 p.m. on November 25, 1948, Ananda Jennings (1894–1971) was seated in the cold, stone-floored Meditation Hall of Nanhua Temple. Empty Cloud (ca. 1864–1959), one of China’s most revered Chan masters, was telling a story. “When the Buddha was alive there was an outsider who came offering flowers with both hands,” he explained. “The Buddha, watching this person approach, said ‘Let go.’ Hearing this, the outsider dropped the flower from their left hand. The Buddha again said, ‘Let go.’ The outsider then dropped the flower from their right hand. Again, the Buddha said, ‘Let go.’ The outsider was surprised and said, ‘I held flowers in both hands as offerings to the Buddha. Now the venerable Buddha has instructed me to let them both go. I have no flowers left, but still the Buddha tells me to let them go. What is the meaning of this?’”

Empty Cloud was the abbot of Nanhua, the remote mountain monastery where the legendary Sixth Ancestor of the Chan lineage—Huineng (trad. 638–713)—lived and taught after receiving dharma transmission from master Hongren (ca. 600–674). Huineng’s mummified body, in fact, still sat on the altar of the monastery’s main hall. As the fifty-fourth-generation lineal descendant of Huineng, Empty Cloud was working to revive his ancestor’s temple as part of his larger effort to reinvigorate the Chan tradition in China. That November, over one hundred monks, nuns, and laypeople had converged on Nanhua to participate in a seven-day intensive meditation retreat. Along with everyone else, Ananda Jennings had been up since 4:30 a.m., alternating hourlong periods of seated meditation with shorter stints of fast walking meditation. Brief evening lectures provided a rare respite from the days’ lengthy silences.

Concluding his comments for the night, Empty Cloud arrived at his main point: “The Buddha, taking pity, explained, ‘I was not urging you to let go of the flowers. I was urging you to abandon the six sense objects, the six sense organs, and the six sense consciousnesses. This is called ‘letting go’.’” Chan practice, Empty Cloud reminded his disciples, demanded that one abandon all attachments. It was a basic tenet of the tradition, but as the story was meant to illustrate, it was not always easy for outsiders to understand.

Ananda Jennings was the first Western woman to participate in an intensive Chan retreat in China. She was, in that sense, very much an outsider. But she had spent the previous two decades studying Buddhist doctrine and practice while living in coastal California, and she felt a special affinity with the Chan tradition. The reason she had come to China, she told the monks at Nanhua, was to study the sudden teachings of the Chan school, which the Indian Patriarch Bodhidharma had transmitted from India some 1,500 years earlier. After learning that those teachings still flourished in China, Jennings determined to visit the body and the monastery of the celebrated Sixth Ancestor and study under an awakened master of the Chan lineage. Like Bodhidharma, she felt called to enact a transmission of the dharma, not from India to China but from China to the United States. Jennings, who had converted from Christianity to Buddhism in her 30s, was thus a new kind of missionary. She devoted her life to spreading the Buddhist teachings in the Christian West.

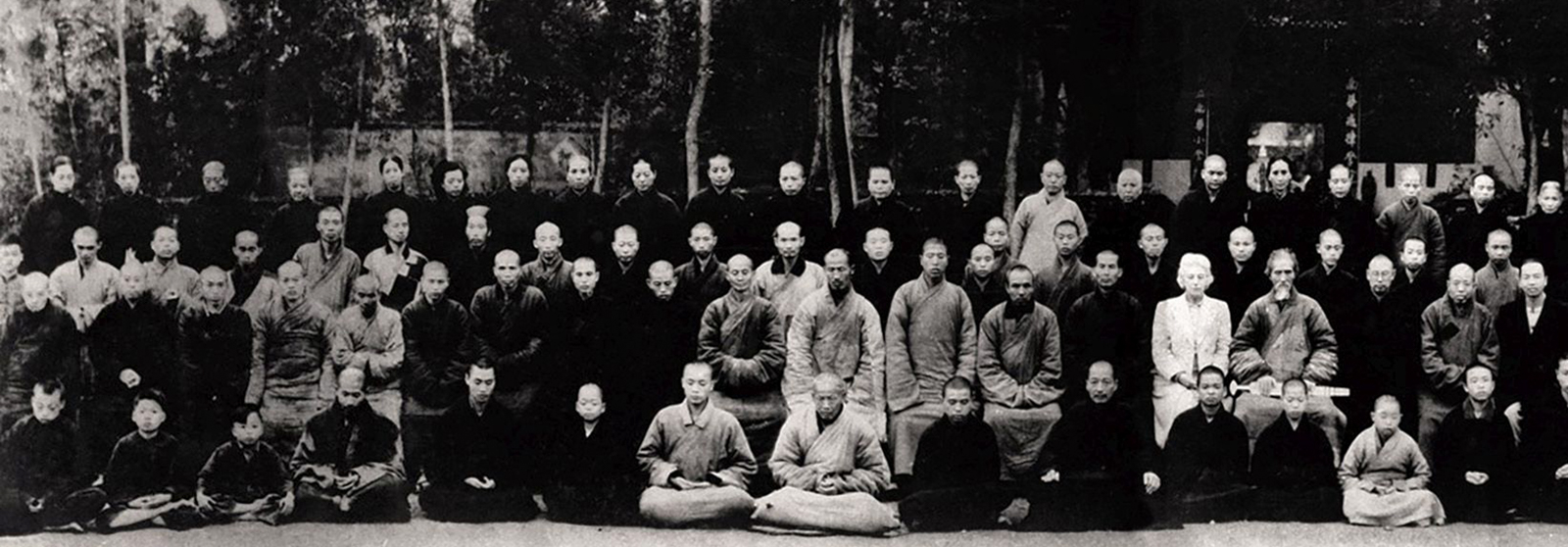

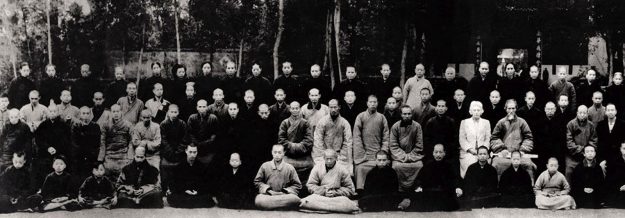

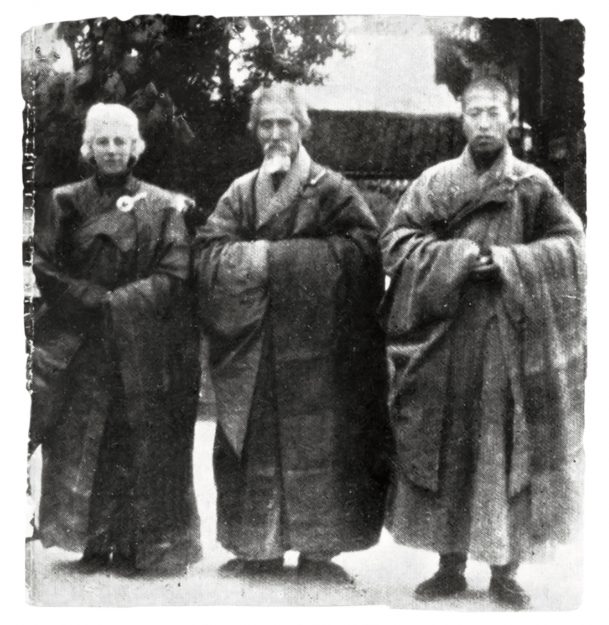

At the conclusion of the retreat, participants gathered for a group photo outside the monastery’s gate. In the image, Empty Cloud sits in the center flanked by 118 men, women, and children. Almost everyone is dressed in the drab black, gray, blue, or brown robes typically worn by monastics and laypeople. The 54-year-old Jennings, with her medium-length white hair, pale white skin, and crisp white dress suit, stands out. Sitting to the right of Empty Cloud, she almost glows in the old black-and-white photo.

The monks staying at the monastery were understandably curious about both Jennings’s path to Nanhua and her understanding of the Buddhist teachings. While she was there, a monk known as the “Mendicant” (Qishi) questioned Jennings with the help of a layperson who spoke some English. Their conversation was deemed significant enough to transcribe and later publish in a local journal. It begins with Qishi asking Jennings about her intentions.

Qishi: You have sailed across the sea to come to China, to meet Venerable Empty Cloud, visit Nanhua Temple, venerate the Sixth Ancestor, and sit a seven-day Chan retreat. What is the point of expending so much effort?

Jennings: To study the buddhadharma.

Qishi: Those who study the buddhadharma must understand life and escape death. If one does not understand life and escape death, they will be unable to study the buddhadharma. What is your understanding of life and death?

Jennings: Fundamentally, there is no life and death. What use is understanding and escaping?

Qishi: Since there is no life and death, why must you study the buddhadharma?

II

Ananda Jennings had spent many months traveling to Nanhua Temple from her home in California. Why did she expend so much effort to study Buddhism in China? As a Western woman in a Chinese Chan monastery, she was venturing into unfamiliar territory, but she was also following in the footsteps of a handful of Americans and Europeans who had developed an interest in Buddhism after living and traveling in China. Like Jennings, most of these Westerners were reared as Christians. Several, in fact, had initially come to China as missionaries. Their turn toward Buddhism went against the grain. Most missionaries harbored an undisguised antipathy toward Chinese Buddhists.

Like Bodhidharma, she felt called to enact a transmission of the dharma, not from India to China but from China to the United States.

The Reverend William Remfry Hunt (1866–1953), for example, had been living in China for over twenty years when he described the native religious traditions as “black rot” whose only remedy was eradication. “The debris of Confucian, Buddhistic, and Taoistic systems is as the parasitic smut and worm dust of the East,” Hunt pronounced. “In lands where every prospect pleases and only man is vile, this moral blight has not only to be destroyed, but buried deep in its grave, and the humanity endangered by it kept in careful quarantine.” For missionaries like Hunt, it was obvious that the religious traditions of China promoted “filth, murder, lying, demonology,” and sin. “Anyone who has seen heathenism in the streets, homes, highways, temples, among its priests and patrons in the gilded palaces, as well as in the hovels, will never, unless his sense of refinement is a minus quantity, flatter, fawn, or wink at its darkness and sin. No!” If Buddhism was a disease infecting the people of China, missionaries were paramedics, and Christianity was the cure.

Some missionaries were more sympathetic to Chinese religious traditions, and a few even developed an abiding admiration for the Buddhist monks they encountered. Dwight Goddard (1861–1939), who served as a Congregational missionary in China, eventually converted to Buddhism and published The Buddhist Bible to make some of the tradition’s sacred texts available to Anglophone readers. The Norwegian Lutheran missionary Karl Ludwig Reichelt (1877–1952) became convinced that Mahayana Buddhism was an outgrowth of Christianity and founded the Nordic Christian Buddhist Mission in the city of Nanjing to nurture Buddhist-Christian dialogue. One of the most prominent early evangelists of Buddhism in the West, Alan Watts (1915–1973), was an Anglican priest. These were all educated men of “refinement,” to use Hunt’s term, and yet they saw Buddhism not as a “putrid sewer” but as a deep, sophisticated, and largely benevolent religious tradition. “The Buddhist ideals of purity, goodness, moral beauty, mercy, kindness, love, faith, [and] trust,” wrote Goddard, “are identical with Christian ideals.” Ananda Jennings came to a similar conclusion, and she made the long and arduous journey to China with the intention of bringing these ideals to the West. The Reverend William Remfry Hunt would have been scandalized. Not only did Jennings’s efforts run counter to his attempts to destroy Chinese Buddhism through displacement, but the agent of this sabotage was none other than his own daughter.

III

Jennings: Originally, there is no Buddha. The student is Buddha.

Qishi: A Buddha has thirty-two major marks and eighty minor marks. When he presses his toes into the earth, an oceanic seal radiates light. Can you do this?

Jennings: Can, cannot—these are both frivolous statements.

Qishi: What you say is true and demonstrates a subtle understanding. Talking about eating, however, does not satisfy hunger. Can you express the ultimate in a single sentence?

Jennings: The ultimate has no sentence. Speaking of emptiness is also empty. If you will permit some rambling words: inconceivable awakened nature is the mother of the ten thousand things.

Qishi: Everything you have said accords with the ancestors’ intentions, but the single word “knowledge” is the gateway to all misfortune. You are a person of understanding, so let me complicate matters by asking you: without speaking, what is your original face?

IV

Ananda Jennings was born Mabel Hunt on April 22, 1894. Her father, William Remfry Hunt, had come to China from England six years earlier as a member of the United Christian Missionary Society. The Reverend Hunt studied Chinese and even translated some works of Chinese literature, but he devoted most of his energies to selecting and training Chinese Christian evangelists. In the spring of 1893, he married Annie Louisa White. The couple was living in Nanjing, where Hunt was working at the Red Cross Society and teaching at seminary, when Mabel was born.

Mabel was the eldest of five children, all of whom were initially homeschooled in the Hunt household. Their education involved extensive Bible study, and the children inevitably absorbed the conservative Christian views of their parents. At the age of 11, Mabel announced her future plans: “When I grow up and am able to be a missionary in China, I shall be so glad to tell these poor people who bow down to their idols of the dear, loving Jesus, and to lead them to Him.” Her father’s scathing critique of Chinese religions, Heathenism Under the Searchlight, was published just three years later.

Most European and American missionaries working in China sent their children abroad for secondary schooling. Mabel accordingly traveled to the English town of Seven-oaks to attend Walthamstow Hall, an all-girls academy that catered to the daughters of foreign missionaries. She would later remember her favorite mistress at the school, a young woman named Emily Buchan, who taught physical education and domestic economy. In an uncanny twist of fate, Buchan was the soon-to-be mother of Alan Watts, born just a few years after Mabel graduated from Walthamstow.

At the age of 25, Mabel Hunt married Frank Dickinson Coop (1893–1976), a Christian theologian educated at Cambridge. It was around this time, she told the monks at Nanhua Monastery, that she began to take a serious interest in Buddhism. What initially drew her away from her husband’s and parents’ firm Christian faith is not entirely clear, but her move to California may have played some role. The Reverend Hunt, “worn by the strain of war and revolution,” left China in 1920 and eventually accepted a teaching position at the Baptist Theological Seminary in Los Angeles. Mabel settled in nearby Ojai. In the 1920s and 30s, the small, largely rural town of Ojai was becoming a center of Hindu and Buddhist-inspired religious movements. The Happy Valley Foundation, established by Annie Besant (1847–1933) and Jiddu Krishnamurti (1895–1986), was based in Ojai, as was the Krotona Institute of Theosophy. Neither Theosophy nor the teachings of popular India gurus much impressed Mabel, however. She would later express her disappointment with the British Buddhist Lodge precisely because of its Theosophical origins, and she dismissed the Indian path of “Worship” as inferior to her preferred method of “letting undivided Mind flow through.” Soteriological differences aside, Mabel’s residence in Ojai put her in close proximity to several of the alternative, Eastern-inflected religious communities that were taking root in coastal California at that time.

Mabel’s turn towards Buddhism may have been a factor in her divorce from Coop several years later. As she explained to the author and self-styled mystic Paul Brunton, “The churches very sensibly advocate a normal married life for those on the religious stage. But, in this final stage, which we teach, one has to be alone.” It was therefore imperative, Mabel said, that “whoever wishes to follow this [Buddhist] teaching must give up everything and live like a hermit.” Following her divorce, she began a four-year period of isolation during which, according to her own account, she did not read, did not meet with anyone, did not eat in the evening, and did not “engage in any activity whatsoever.” She emerged from this period transformed. She would later say that after her retirement, “I found to my surprise that all my discoveries therein during meditation were recorded in the Buddhist Bible.” It was probably during this time that she adopted the name of Shakyamuni’s great disciple, Ananda. (How she acquired the surname Jennings, like many other details of her biography, remains a mystery.)

By the 1940s, Jennings was giving Sunday morning teachings at her house in at Whale Rock Ranch on the northeastern edge of the Ojai valley. Her talks were open to all, but select students were granted access to her “advanced teachings.” Those who came to her seeking advice on more mundane matters were turned away. “I refuse to discuss the personal or worldly problems of disciples,” she announced, “as I am living on a level far above all that sort of thing. I refuse to advise any of them.” She believed that the depth of her realization set her apart from other people. “I do not know of any other women who have become Buddhas. I have special work to perform with the Buddhas.”

Jennings’s claims of exalted status can come across as arrogant, but she had a point about the rarity of prominent female Buddhist teachers. In the 1930s and ’40s, English-speaking authorities on East Asian Buddhism were nearly all laymen. D. T. Suzuki, R. H. Blyth, Alan Watts, Eugen Herrigel, and Christmas Humphreys all authored influential books, gave lectures, and established themselves as Buddhist experts. These laymen promoted a tradition that was itself deeply patriarchal; the famed Zen lineage is of course made up almost entirely of men. While no one denied the capacity of women to achieve awakening, there was little precedent for female masters instructing coed communities. In the United States, as in East Asia, women were more often portrayed as the devoted followers of their male masters. Jennings was not satisfied to sit on the sidelines. Although she was unaware of “other women who have become Buddhas,” unbeknownst to her, several American and European women were traveling to East Asia to deepen their understanding of Buddhism. Ruth Everett Sasaki (1892–1967) is the best-known example, but there were others. An incomplete roster of women who engaged in Zen training in Japan would include Miriam Salanave (1876–1943), Kristine A. Segulyev (1884–1964?), Georgia Forman (1871–1955), Ida Russell (1886–1962), L. Adams Beck (Elizabeth Moresby; 1862–1931), and Helen M. Hayes (1906–1987). The biographies and published work of these pioneering figures, unfortunately, have received scant attention. Although some of these women eventually settled in California, Jennings does not appear to have been aware of any of them. She could find no model for what she was attempting to do.

V

Jennings: The Diamond Sutra says, “Anuttara-samyak-sambodhi is not anuttara-samyak-sambodhi.”

Qishi: It seems like this but seeming is not it. If such matters are not received from a master, it would be like [Master] Jiashan never encountering the Boat Monk. Your words are simple, but they accord with principle and agree with the sutras. If you do not cut off the life root, however, you will remain in the realm of intellect. We want you to have a sudden realization.

Jennings: I have only read a very small number of sutras. In the past, I was in sealed retreat for four years. When I emerged and spoke with people, they all said I spoke the buddhadharma. For that reason, what I say is not derived from the sutras, and it is different from intellectual knowledge.

Qishi: Knowledge is not only gained through reading scriptures and commentaries; it is also generated through quiet contemplation. This knowledge can surface from previous lifetimes. Knowledge from past lives is also a kind of intellectual knowledge. You have come from far away; I hope that you will not reject gold to carry straw.

VI

Jennings had indeed come a long way. She was too young to meaningfully engage with Buddhist monastics when she was in China, even in the unlikely event that her parents would have permitted it. Her point of entry into the tradition was not contemporary Buddhist culture but medieval Chan texts. These she accessed mainly through the English translations published in Dwight Goddard’s The Buddhist Bible (1932) and John Blofeld’s The Zen Teachings of Huang Po (1947) and The Path of Sudden Attainment (1948). Goddard and Blofeld, who had both lived in China and spent time with Chan teachers, served as distant guides for Jennings.

In his younger years, Goddard made a fortune as an engineer and inventor, but after the premature death of his wife, he walked away from a successful career to join the Hartford Theological Seminary. Ordained in 1894, he set out for China shortly thereafter. Contrary to many of his fellow missionaries, Goddard perceived a kinship between Buddhism and Christianity. He explored what he saw as their shared purpose in early publications with titles like, “A Vision of Christian and Buddhist Fellowship in the Search for Light and Reality” (1924) and “Was Jesus Influenced by Buddhism? A Comparative Study of the Lives and Thoughts of Gautama and Jesus” (1927). These works, unsurprisingly, were not enthusiastically received by many of his Christian colleagues.

As Goddard delved deeper into Buddhist traditions, he felt particularly drawn to the teachings of Chan and Zen. With the support of D. T. Suzuki, he spent eight months in 1928 at Shōkoku Monastery in Kyoto under the supervision of the abbot Yamazaki Taiko (1875–1966). Back in the United States, Goddard split his time between his native Thetford, Vermont, and Santa Barbara, California, self-publishing his writings and commissioning translations of Chinese Buddhist texts. (Goddard could not read Chinese, and so worked with two native speakers—the monk Waidao and the layman Wong Mou-Lam—to produce the translations.) His The Buddhist Bible brought together English versions of texts central to the Chan tradition: The Lankavatara Sutra, The Diamond Sutra, The Heart Sutra, and The Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch. Reading these works some years later, Jennings felt that they validated the experiences and insights she had arrived at independently while in seclusion.

In the early 1930s, Goddard attempted to establish a new Western Buddhist monastic order called the Followers of Buddha. He envisioned that its all-male community would split their time between his properties in Vermont and Santa Barbara. The movement never took hold, however. Despite his best efforts, Goddard was unable to persuade a Chinese Chan monk to serve as teacher, and as of 1934, the order had just one member. Goddard’s would-be monastery in Santa Barbara was situated near Jennings’s home in Ojai, but there is no record of the two ever meeting. By the time Jennings was preparing to make her own pilgrimage to China in search of a Chan master, Goddard had passed away.

A more immediate inspiration for Jennings’s decision to study Chan in China was John Blofeld (1913–1987), the English author and sinologist whose translations of Tang dynasty Chan texts, she told others, mirrored her own teachings. Unlike Goddard, Blofeld was fluent in Chinese and had traveled extensively throughout China seeking out prominent Buddhist and Daoist teachers. In 1936, Blofeld visited Nanhua Monastery and met Empty Cloud, whom he described as an “almost mythical personage.” In Blofeld’s recollection of their conversation, Empty Cloud was perplexed by his persistent questions about what constituted “pure” Chan (as opposed to Chan that was mixed with Pure Land practices)— “Why insist so much on this difference?” Empty Cloud asked. Blofeld came away from the brief encounter impressed by the old monk’s understanding. It is probably no coincidence that Jennings, who closely followed Blofeld’s writings, also followed in his footsteps, traveling to Nanhua to put her own questions to Empty Cloud and his disciples.

VII

Jennings: I understand that the value of the Buddha’s teachings lies in realization, so I do not place much weight on intellectual knowledge. But what actually is realization? Please be compassionate and instruct me.

Qishi: Realization is not getting mired in the sutras and commentaries and not clinging to appearances. When you raise a single thing, from head to tail, tail to head, every aspect is the buddhadharma. Everything is reality. From beginning to end, the ancestors’ teachings all elucidate this. As for this, it can be spoken of, but it is without substance. Do you understand?

Jennings: The buddhadharma is fundamentally pure awakened nature. I understand that there is not a single thing, but I dare to ask: what is the mental state that understands that there is not a single thing?

Qishi: An excellent question! This understanding that there is not a single thing is something the ancients manifested in many ways. These days, we must adapt to circumstances and make use of clumsy words to explain it, saying, “Treasure mirrors in all directions illuminate all things without obstruction.”

Jennings: I have heard that in China, the ancestral masters of the Chan school use form to illuminate the mind, holding up a flower to transmit the teachings. Allow me to ask, leaving behind words, what can be used to express the totality of the buddhadharma?

Qishi: Did you see that sparrow fly past?

VIII

Jennings’s first stop on her journey to China was England, where she visited Christmas Humphreys’s Buddhist Society to inform the group of her intention to tour the world in support of the “Buddhist world movement.” While in London, she also met Francis Story (1910–1972), an Englishman who had served in the medical corps in India during World War II. Following the death of his wife, Story resolved to return to India to devote himself to the study and propagation of Buddhism. He and Jennings made the next leg of the journey together, presumably traveling from London by steamer through the Suez Canal, down the Red Sea, and across the Arabian Sea to arrive at the port of Bombay three weeks later. From Bombay, they made their way to Sarnath, where they stopped for a month at the Maha Bodhi Society. Story took the new name of Priyadarshi Sugatananda and was henceforth known as Angarika (Lay Renunciant). Jennings began dressing in saffron robes and was called Mahopasika (Great Laywoman). The two converts appear to have acquired some standing in India; when they arrived in Calcutta, they were invited to speak at the Maha Bodhi Hall.

In Jennings’s address, titled “The Gnosis of Buddhahood,” she summarized what she saw as the underlying message of the Buddhist teachings, namely that the duality and relativity that characterized ordinary human thought must be transcended to arrive at a state of pure awareness. This insight, she explained, had been perfectly expressed by Zen masters in China and Japan, but, except for the few individuals who were “completely illumined,” such teachings were very rarely realized. In Jennings’s estimation, the minds of most people were divided, or “split.” They made false divisions between self and others. The “Gnosis of Buddhahood” that she extols in her talk thus refers to the unified knowledge that she believed constituted awakening. Such understanding collapses the distinction between subject and object: “With the Gnosis comes this Knowledge which no longer burdens the mind with concepts of a subjective self thinking about the way out; but the Knowledge that is Itself the way out. For in the twinkling of an eye, one knows, and is free!”

Shortly after delivering this talk, Jennings set sail for Ceylon. There she made the case to the International Buddhist Study Circle that young Ceylonese monks should be sent to Western countries as missionaries. She then continued by ship to Singapore, where an article published in the newspaper The Straight Times, with the byline “our woman correspondent,” marveled that this “slender, white-haired American” woman dressed in yellow robes was planning to meditate in China. Jennings told the reporter that she was part of a movement among Western thinkers to study the essence of Buddhism. Having lectured in India and Ceylon, she now hoped to address the Buddhists of Singapore. But her layover would be brief. She explained that she was expected in Hong Kong to meet the great monk Empty Cloud.

When Jennings’s ship docked in Hong Kong on October 25, Empty Cloud, who was then staying at Liurong Monastery in the city of Guangzhou, already knew that she was coming. A government official had sent a communique informing him that an American woman had requested an audience. For the sake of the diplomatic relations between China and the United States, the official urged Empty Cloud to receive her. When Jennings arrived at Liurong Monastery some days later, she prostrated herself before the elderly monk (then reputed to be 109 years old). Empty Cloud, noting her sincerity, agreed to let her accompany him and his entourage to Nanhua Monastery, roughly 150 miles away to the north.

It was a dangerous time to be on the road. The civil war was raging and the route to the monastery snaked through forested foothills and mountains that sheltered encampments of Communist guerillas. On November 15, three regiments of Communist troops slaughtered a battalion of Nationalist soldiers conveying supplies up the Dong River, 160 miles east of Nanhua. Five days later, more Nationalist troops were ambushed and killed even closer to the monastery. Local officials, not wanting to risk the safety of this distinguished foreign visitor, dispatched a contingent of soldiers to escort Jennings to Nanhua. She arrived at the monastery unscathed, but the troops created some problems along the way. As she explained to Empty Cloud, “The soldiers sent to protect us unintentionally caused the trouble—for force is naturally met with force and resistance.” Empty Cloud, acknowledging that troops could surreptitiously use her visit as an opportunity to harass and intimidate local people, entrusted her wellbeing to the protective spirit of Bodhidharma. Safe at Nanhua, Jennings paid her respects to the lacquered body of Huineng. She also formally took refuge with Empty Cloud, receiving the Dharma-name Kuanhong (“Great Vastness”).

Jennings’s conversation with Qishi took place around this time. In the transcript, we see Qishi probing and at times challenging her presentation of the teachings. Could she go beyond words to directly express her understanding? During her talk in Calcutta two months earlier, Jennings had urged her audience to seek a mental state free from dualities. Qishi, however, gently gestured to the dualism that still seemed to linger in some of her statements.

IX

Jennings: Nothing exists outside of awakened nature; I already understand this.

Qishi: This is not the principle of Buddhism. That is why we say that the one word “knowledge” is the gateway to all calamities. The root of your knowledge runs deep, but it is like adding feet to a painted snake. Now I will use a little demonstration to illustrate the incomprehensible teachings of the ten directions and three worlds. Please pay attention. I am filling this teacup with tea. This is an expression of the one dharma. Now if I take the tea in this cup and pour it out and then turn the teacup upside down, this is also the one dharma. Then again, if I were to pick this teacup up and toss it behind me, the teacup would immediately shatter. This is also the one dharma. In each of these things, the dharma is complete. If you know this, you know. If you do not know, it cannot be discussed.

Jennings: The buddhadharma is incomprehensible; I have long intuited this. I am exceptionally grateful to receive the master’s compassionate instruction. Now that we have finished, I would like to request that the master and the venerable monk Empty Cloud come to the United States to spread the dharma. Would this be possible?

Qishi: In recent years, Venerable Empty Cloud has been expending all his energy day and night to restore Yunmen [monastery]. People from all the provinces in this region also invite him to come and spread the dharma. Telegrams are constantly arriving, and many people come to meet with him. This happens many times each month. Now the great disciple requests the Venerable to go to the United States to spread the dharma. Because my capacities are shallow, I am afraid it will be difficult to realize at this time. I am ashamed that I have no way to spread the dharma; my insufficient language abilities would be an obstruction. Let us wait until conditions are right and language is no longer an issue. Then we can decide.

X

What did Empty Cloud and the monks at Nanhua make of Ananda Jennings? Although she had spent her younger years in China, she spoke no Chinese. She had traveled a long and dangerous road back to her natal place, and she had done so essentially alone. At Nanhua, she kept the rigorous schedule, sitting upwards of ten hours of meditation every day and sleeping only four and a half hours each night. She ate simple vegetarian food, slept in communal living quarters, and used pit toilets. The monks and laypeople would have been accustomed to this way of living. Jennings, on the other hand, had lived a life of relative comfort. Nanhua was a far cry from her spacious ranch in Ojai. She did not have to travel halfway around the world to spend a week in Nanhua’s meditation hall, yet there she was.

Empty Cloud seemed to be impressed by both her knowledge and her tenacity. He had met thousands of devotees, only a small number of whom merited a mention in the autobiography he later wrote. Jennings, perhaps because she had come all the way from the United States to call on the master, made the cut. Empty Cloud’s entry for the year 1948 reads, “In the winter, an American woman named Jennings came seeking the precepts. A seven-day Chan retreat was held. She left full of joy.” The editor of Empty Cloud’s autobiography, Cen Xuelu (1882–1963), noted with regret that although Jennings “had some practice and realization, she unfortunately lacked the ability to communicate” in Chinese. Fayi, the monk who first published the dialogue between Jennings and Qishi, also expressed his admiration for this Western woman. Not only had she diligently studied Buddhism for over twenty years, but she also traveled to several countries to engage with various Buddhist masters. For that reason, Fayi observed, her understanding of the teachings was exceptional. By publishing the transcript of her dialogue with Qishi, Fayi hoped to show his colleagues that “the study of Buddhism in the West is actually not superficial.” This revelation, he suggested, should inspire Chinese Buddhist monks to go to the West to spread the dharma.

Despite Jennings’s entreaties, neither Empty Cloud nor Qishi ever did make it to the United States. The Communist Party marched on Beijing shortly after Jennings’s departure, and Empty Cloud was arrested at Yunmen Monastery in 1951. The beatings he endured left him with several broken ribs, and he was unable to eat for nine days. He was eventually freed and went on to serve as the honorary president of the newly formed Chinese Buddhist Association. Despite multiple invitations to relocate outside the borders of China, Empty Cloud continued his work in the mainland until his death in 1959. It fell to two of his disciples to bring his teachings to the West. Jy Din (1917–2003) arrived in Honolulu in 1956 and established the Hsu Yun [Empty Cloud] Temple a decade later. Hsuan Hua (1918–1995), who had met Jennings during her time in China, settled in northern California in 1962 and founded the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas in 1974.

Ananda Jennings never studied with Empty Cloud’s successors in California or Hawaii. After her return to southern California in the early months of 1949, her life becomes difficult to trace. The 1950s and ’60s represented the height of the so-called Zen Boom in the United States: D. T. Suzuki lectured at Columbia; Kerouac published On the Road and The Dharma Bums; Shunryu Suzuki established Tassajara, the first Zen monastery in the United States; and Martin Luther King Jr. nominated Thich Nhat Hanh for the Nobel Peace Prize. Jennings’s dream of bringing Zen to the West was finally being realized, but she played no visible role. She wrote on Buddhist topics, occasionally publishing her teachings in periodicals, but she never attracted a significant following, had no known disciples, and never established a center. She died in 1971 in relative obscurity.

In the end, Jennings may have left a deeper impression on Chinese Buddhists than she did on convert communities in the United States. The photos documenting her visit to Nanhua were published and preserved in China. The most detailed accounts of her life are also found in Chinese journals and newspapers. Despite her remarkable biography and her concerted efforts to promote Buddhist teachings in the West, she is barely mentioned in English-language sources. We can only speculate about why this devout, driven, and accomplished woman has faded so completely from the collective memory of American Buddhists. Was she not charismatic enough? Did her teachings simply not resonate with American audiences? Was it because she was a woman in a movement dominated by men? Whatever the case, although she was inspired by the example of Bodhidharma bringing Chan to China, Jennings was ultimately unable to enact a similar transmission in the West. And yet her missionary work did succeed, if in unanticipated ways. Rather than conveying Chinese Buddhism to the United States, Jennings introduced aspects of American Buddhism to Buddhists in China. Through her efforts and her example, Empty Cloud and his community learned of Western converts’ sincere commitment to the dharma. In this way, Jennings helped to lay the foundation for exchanges that continue to this day. Traveling from afar to find common cause with the people of China, she was, in her own way, following in her father’s footsteps.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.