Our world is saturated with images: from ads to Instagram, television to storefronts, we are accustomed to the messengers of visual culture. Marie Howe, New York State’s Poet Laureate from 2012 to 2014, wants poetry to inhabit the public in a similar way. What if there were poems posted in bus stops, on street signs, or beside park benches, poems waiting to remind us that we’re not alone?

Influenced by Buddhist ideas and fueled by an impulse to share what she finds astonishing, Howe is an advocate for bringing poetry off the bookshelves and into the living world. On April 21st, National Poem in Your Pocket Day, people do just that: they select a poem to carry and share with others. On the occasion of Poem in Your Pocket Day, Tricycle spoke with Howe about the “disappearing self” of the creative process, Dickinsonian despair, and how poetry can contribute to our daily conversations.

—Marie Scarles, Editorial Assistant

Are there any poems that you are currently carrying “in your pocket”?

I write—it’s what I do. I carry poems in my body. It’s what I read. It’s what I write. It’s what I love. It’s what I teach. So I carry them with me every day, all the time. My whole life has been informed by poetry. There are so many voices within me at any given moment. I’m always talking to writers who are practicing this craft, and I’m constantly going to poems, not from my bookshelf but from my mind, to say, “Do you know this poem?” It’s what I’ve been doing for 35 or 40 years.

For the majority of the population who don’t live and breathe poetry, how might poems enter their daily discourse?

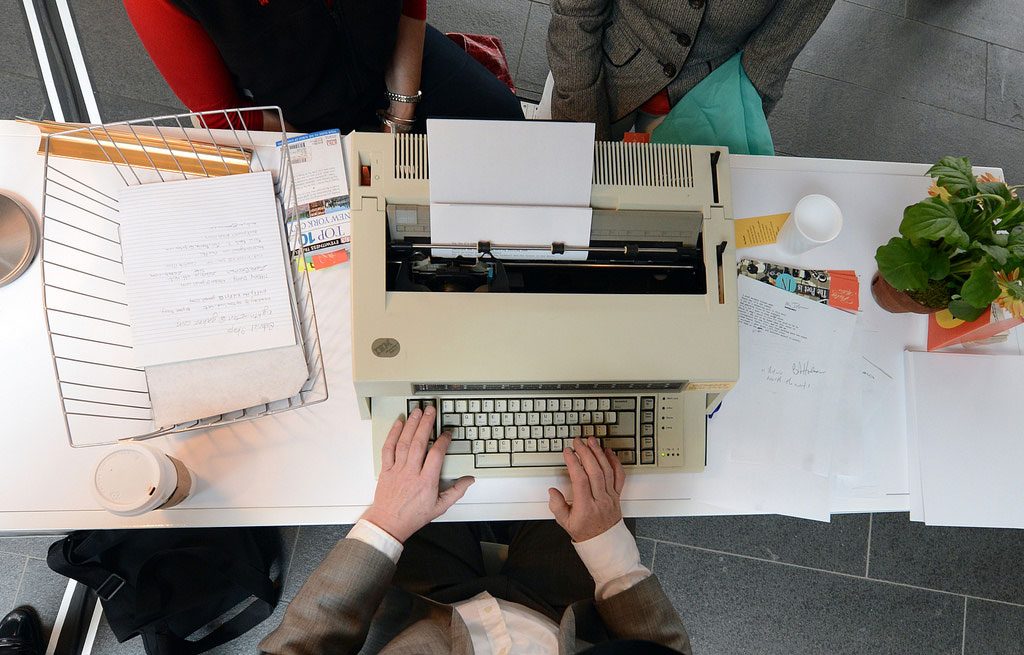

I think that people are often looking for and reaching for poems. If you live in New York City, you might see a poem on a subway or on a bus because of the MTA’s Poetry in Motion project. And when I was the New York State Poet, we put on two different events in public spaces where we had published, award-winning poets sitting at desks with typewriters for six hours. People could come and sit down at any one of those desks and speak with the poet, and then the poet would write that person a poem on the typewriter. When they were done, they would sign it and date it, read it to the person, and then give them a copy. People waited two and a half hours in line for that experience.

The gift goes two ways. Someone you don’t know sits down at a desk and speaks with you about what’s important to them. Then the poet pulls that in, and through the power of language and music and image and silence, transforms what they heard into something that the person who spoke with them will recognize as them. It was extraordinary. We called it “The Poet Is In,” and my dream is for it to be a permanent installation at Grand Central Terminal.

What do you think this space represented for people? What were people waiting hours for?

I think people had all sorts of reasons for waiting that long. They were old people, young people, school kids, sanitation workers, retired people, people with their children in strollers. Every color. Every nationality. One man sat down across from a poet and said, “Will you write a poem that will bring my wife back to me?” One young woman visiting from China said, “Will you write a poem about my beloved so I can give it to her? Lesbian love is not allowed in China.” There were those who sat down and said, “I don’t even know what to say.” The poet asked them questions to elicit images or important memories. A poet might say, “There is an invisible door in the air: You can’t see through it, but there’s something behind it. Do you want me to open it?” Then she would say: “What do you want to be behind the door?” People would say things like, “My daughter who died when she was 10.” Or, “My grandmother’s eyeglasses.” Or, “That red dress I lost in college.”

These examples make me think that poems arise in moments of need, or that they witness our world.

Poems do everything. They witness what’s happening and they recall. We’re still reading poems that were written 2,000 years ago. After 9/11 there were these huge bed sheets in Washington Square Park around the arc, and everyone wrote on them, attaching poems and adding pictures. In the weeks that followed hundreds of people read what was on those sheets. I think that was an extraordinary time when there were poems everywhere: on the closed doors of firehouses and all the posters for the missing people.

If you could post a poem on a billboard today, what poem would use?

I cannot choose among thousands and thousands of poems one poem that I would put up on a billboard right now. I would put up 60 throughout the city. There’s no one single poem that can hold everything in the world. Also, poems aren’t meant to be used. They’re meant to just be there, like a living voice. We listen to each other. I was talking to [the poet] Billy Collins a few weeks ago, and he said, not everybody has to like poetry. It’s like jazz—there’s a certain percentage of the population that loves jazz, and the rest of the population doesn’t care about it. That’s fine. Why should we push jazz on people? If you’re pulled towards it and you love it, you love it. There are a lot of people who don’t watch baseball. But there are people who can’t imagine life without baseball. The same is true for poetry. Emily Dickinson wrote about what it was like to be in absolute despair. She lived through it and she left evidence of her living through it in a gorgeous poem. People find it, read it, and feel less alone. They feel absolutely charmed by the way she said such difficult things. It’s a gift.

You brought up Dickinson’s despair, which makes me think of the four noble truths, the Buddha’s teachings on suffering. Do you think poems can make life more livable?

I certainly have been influenced by these ideas. We all have. Poetry says: “I was here.” Whenever we hear another human say “I was here” we are less alone. One expression this [discussion] reminds me of is “the full catastrophe” [from a Jon-Kabat-Zinn book]. Poetry speaks to the full catastrophe. Poetry speaks to the deepest experience we have. It can also speak to the silliest. It speaks about what it is to be alive and to know we’re going to die. We write things down because we live in time, because we know that we’re here and that we’ll be gone. All art does that. But we’re talking about poetry—that’s what it does. We used to believe in spells: if you said something in a certain ritualistic way, it would happen. That was poetry. We used to believe that if you said the right words in the right order, you could make someone fall in love with you. That’s poetry. Poetry can remember people, it can elegize people, it can protest unfair governments. Poetry is as broad and wide and deep as human discourse can be.

How do you view the relationship between the self and the act of creating?

The best thing about writing is that I don’t know what I’m going to get back. The great release of writing is that you have to apply the self as an instrument on the page. Then, if you’re lucky, it disappears. There’s something else that happens, which people call creativity or the imagination. You’re a part of a process that is actually happening and it’s beyond you, beyond the self. It’s wonderful. It’s what we long for: to be free of the “I, I, I, me, me, me.”

That’s a beautiful way of putting it. Before you go: What poem do you think you’ll share on Poem in Your Pocket Day?

I’ve been thinking about one really brief poem by Galway Kinnell. It’s three lines. It’s called “Prayer.”

Whatever happens. Whatever

what is is is what

I want. Only that. But that.

That’s a poem I say to myself a half a dozen times a day.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.