“Form is emptiness, emptiness also is form; emptiness is no other than form, form is no other than emptiness.”

This phrase is from the Heart Sutra, the heart of the Mahayana teachings, the pith of the Prajnaparamita Sutras. The Buddha really punctured concepts with these lines! This was the first time my mind stopped. The Heart Sutra was the first piece of buddhadharma that I devoured; I even memorized it so I wouldn’t be without it, because it was both frightening and freeing. To think, all this, all this experience and solidity that we place as we move through this world, all of it is both solid and evanescent. It was the first piece of dharma I encountered that spoke to the nature of my fluid being. I just happened to be born of this female body and it is not fixed. I felt, once again, the dharma gave me the practice opportunity to view how my form emerges and dissolves in every moment. And as frightening as that was initially, I gradually practiced to remember that it wasn’t a dissolve into nothing, but an emptiness so vast it accommodates everything.

This was tested on two very important periods in my life. For most of my life, I hated who I saw in the mirror: plastered in scars, acne, and a disfigured body that was perpetually prepubescent. As I approached any mirror, echoes of abusive taunts would ripple at me, so I hung mirrors below the neck or didn’t look at them at all. During a month-long silent meditation program, a dathun, I decided to spend time with my reflection and realized my worst fears erupted in taunting thoughts, then dissipated. Another wave, of different insults and content, arose and dissipated. I actually didn’t know who that reflection was. So I got curious. I asked it. I began to notice the faces of several family members and of no one at all. This shifted something for me. Perhaps I wasn’t who I thought I was.

Later, my mother was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s and I returned home to care for her. Over the next year and a half, I moved from “only daughter” to whomever she decided I was in the moment. Initially, I was not only sad but irritated that she would forget my name, of all people. In that moment, the clutch onto my existence and identity became personal. I felt my “I” disappearing. I would constantly correct her, quiz her, show photographic evidence, all for her to remember. After a few times of losing my patience, praying to the dralas [or in Tibetan Buddhism, something that “cuts through one’s habitual chain of thoughts,”] for clarity did note the impact of my righteousness. My mother would grow more irritable or worse, sad, as she momentarily realized I was correct and, even more stunning, that she’d forgotten and would continue to forget. When I took in her pain, when I felt how out of control it must feel to, for any given amount of time, have no reference point, I was grateful for the ingenuity of mind to pull some memory and place it in the present.

It was then these teachings became more salient. I began to be less uptight about my identity and more focused on the energy of the interaction. I was able to feel all the love my mother had for me, all the while calling me her sister, or friend, or mother. There was a knowing, an is-ness that was beyond any conceptual picture of who I thought I was, who I knew myself to be, who I thought I was to her. That is-ness was made of goodness and love. It eased her nerves, and more play was invited because there was space.

One of the last sentences I heard my mother speak was, “I love how you make me feel.” It was then I saw the dharma in action, that the energy of our being is what is felt by others. So, even regarding my gender, I found tremendous freedom to manifest as whoever emerged in that moment. For me, this is the invitation of being nonbinary: the concepts of either male or female are not fixed ways of being but rather a flow, free to rise spontaneously and then subside.

♦

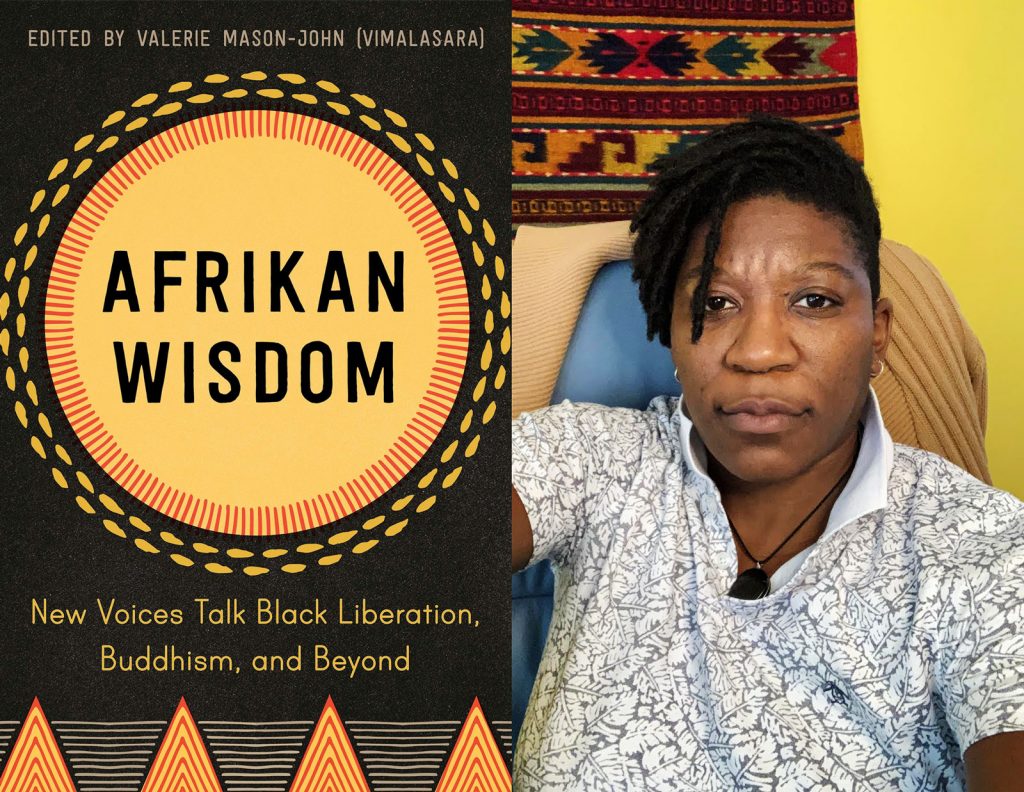

Adapted from Afrikan Wisdom: New Voices Talk Black Liberation, Buddhism, and Beyond edited by Valerie Mason-John, published by North Atlantic Books, copyright © 2021. Reprinted by permission of the publisher.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.