For nearly two decades, I lived as a monk in Theravada monasteries, experiencing moments of inspiration, bliss, doubt, stubbornness, insight, disappointment, surrender, hope, and failure. I delved into an extensive reading of the suttas, absorbed countless teachings, and engaged in reflexive thinking. My approach involved amassing information from diverse sources and seeking the common thread that unified them all. This seemed like an effective approach, at least for a while.

Yet, the most agonizing aspect of this method was the struggle to preserve and retain those realizations. I yearned to cement my insights as a blueprint, ensuring that my accrued “wisdom” could anchor my inner peace and serve as “wisdom” for prospective listeners. However, sustaining serenity amidst an overwhelming sea of information became increasingly challenging.

One day, I stumbled upon a translation of the Atthakavagga, a compilation of texts making up the fourth chapter of the Pali canon’s Sutta Nipata. I was captivated by its markedly different style of suttas, which departs from the technical, rigidly structured texts found in many other texts. This chapter—one of the oldest compilations in the entire canon, sometimes viewed as revealing an early form of Buddhism grounded in rejecting all views—was freer and carried a more natural tone that deeply resonated with me. I was struck by the wisdom contained within its concise verses. I cherished the idea that all I needed by my side was that singular book.

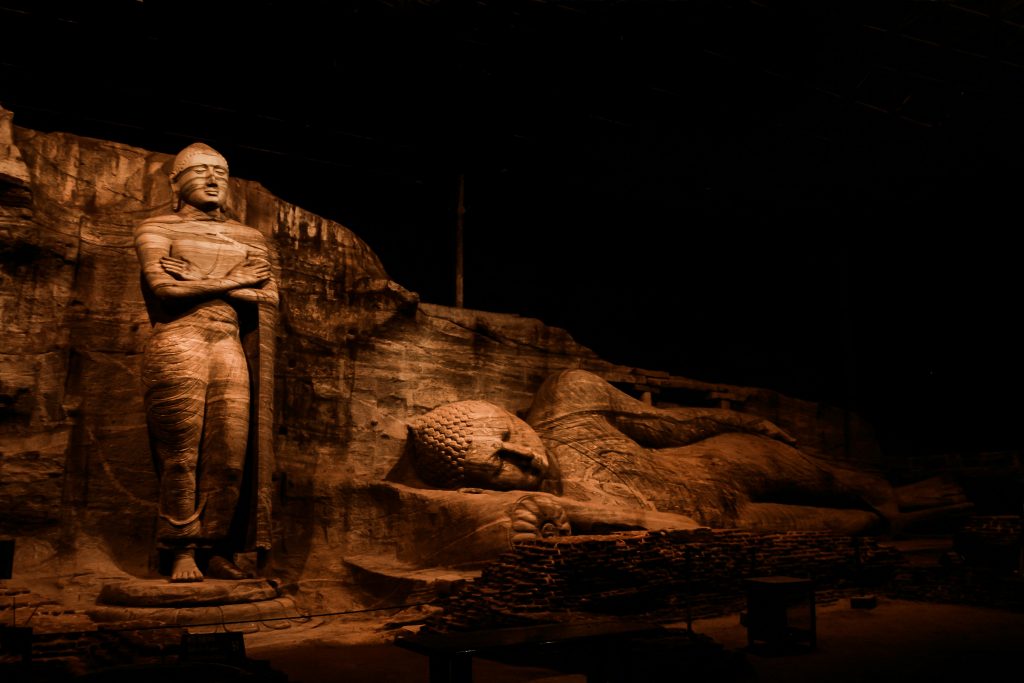

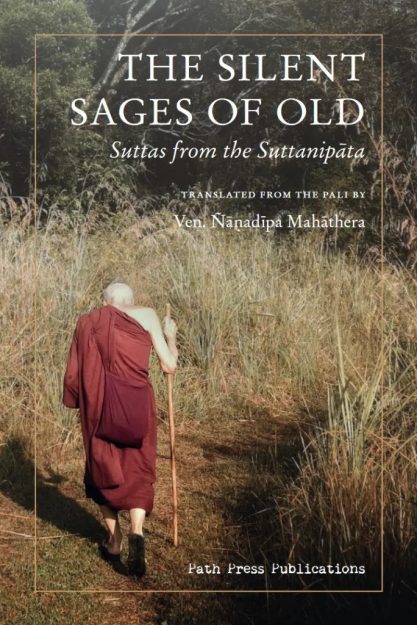

But, I was acutely aware of the subtle nuances within the Pali texts, and I knew I had to tread carefully in interpreting them. Deep down, part of me harbored a hope that one day, this profound book would be translated, not by some detached academic but by someone living the noble life of a hermit monk. In my heart, I knew that person could only be Venerable Nanadipa Thera. The French-born Danish-raised monk was ordained as a novice (samanera) in 1969 and as a monk (bhikkhu) in 1971, living most of his life as a hermit secluded in remote areas of Sri Lanka. He had a special understanding of this text, and if I were to further my comprehension of the Atthakavagga, it would be through Bhante Nanadipa.

I embarked to Sri Lanka to meet Bhante Nanadipa, even though the journey to his remote abode was anything but easy. I can vividly recall that initial trip—a lengthy expedition through winding streets, then a turn onto a desolate gravel path flanked by isolated houses and outlying roads. Eventually, when the car we traveled in could go no farther, we continued on foot, trudging through a forsaken hamlet. Behind one of the houses, a path emerged, leading us up a mountain path into the dense jungle.

After an hour of sweaty ascent, there was Bhante Nanadipa, serenely seated in his simple hut (kuti) without a front wall. His humble dwelling was made up of a hard wooden bed, a tiny table, and a small cupboard for medicines. I shared my deep connection with the Atthakavagga, and to my delight, he revealed his fondness for it, having committed the verses to memory. With a bit of persuasive conversation, I convinced Bhante to translate the hallowed verses. I emphasized that he, with his expertise in Pali and profound understanding of the text, was uniquely qualified. Although initially hesitant, he eventually translated the Atthakavagga in 2016 and subsequently the Parayanavagga in 2018, both published together under the title “The Silent Sages of Old.” I am forever grateful for this book and regard it as a cherished guide. Bhante passed away in 2020, and this stands as one of his most important contributions to the world.

I worshiped the Atthakavagga so much that I even translated it into my native Slovenian language. Its central message emphasized a crucial lesson: not to be overly confident or assured in myself because all my picked-up beliefs are uncertain. My perspective, beliefs, and intelligence alone won’t grant me freedom from suffering. Everything that arises will eventually fade away. All formulated phenomena will perish, and every construction will ultimately be demolished. Whatever I imagine or whatever concept I hold, it will always be uncertain. No formulated truth can claim to be the ultimate knowledge. Eventually, I learned that the path lies in the comprehension and mindful understanding of how the nature of experiences take shape, and not to be fascinated by specific experiences. As proclaimed by the Buddha:

“The root of expanse-and-name,

the “I am,” the deep thinker should put a complete end to.

Whatever cravings are within,

for dispelling these, he should always train mindfully.Whatever thing he would directly know,

whether in himself or outside,

that he should not build up ‘strength’ upon,

for that is not called quenching by the good.By that he should not think himself to be better,

or to be lower or equal.

Contacted by many forms

he should not stay making out himself.Only in himself should he come to peace,

a monk should not seek peace from what is other.

For the one come to peace in himself

there is not the assumed, from where the rejected.” (Att 14:2–5)

Truth isn’t found by merely connecting logical dots or filling gaps with preferred beliefs in the immediate layer of analysis. Instead, it resides in comprehending the formation of our widest spectrum of experiences, acknowledging that nothing exists independently and that everything remains within the realm of conditions. This realization taught me to never hold too firmly on to my intellectual grasp but, instead, to remain discerning of how phenomena are constructed. The Buddha warned:

“He whose ideas are formed, constructed,

and preferred, not having become purified,

whatever he sees as an advantage in himself

he relies on that—a peace dependent on the shakeable.” (Att 14:2–5 3:5)

The teachings I gleaned from those suttas have also become invaluable to my work in existential psychotherapy. I’ve come to understand that much of the suffering experienced by individuals dealing with depression, anxiety, or other psychological disturbances stems from the assumption of a separateness between “me” and “the world.” Yet this assumption, this notion of separateness, is deemed as a wrong view and leads to nothing but dukkha—suffering. When one nurtures the idea of a separate self to such an extent, an individual becomes vulnerable within their own world.

This vulnerability can manifest in various ways. Some may develop a fear of the dangers they perceive the world could inflict upon them, leading to anxieties and phobias. Others might adopt a defensive stance, constructing a fortified ego-self at the expense of those they perceive as weaker, asserting control over others. With such a viewpoint, expectations emerge concerning how others should please, love, obey, entertain, validate, and ensure one’s safety. Paradoxically, the more one tries to control and measure the world, the more one experiences fear and apprehension.

The Atthakavagga discusses the growth of worldly turmoil through the concept of papanca, which I translate as “established proliferation” or spreading out. Papanca encompasses our entire operation: how we think, carry out tasks, and interact with others. This “proliferation” doesn’t just increase desires and the accumulation of material possessions; it amplifies dissatisfaction, fear of loss, anxiety, stress, neuroses, depression, feelings of being adrift, and a sense of purposelessness. Papanca gradually diminishes when one ceases to find delight in fixating on or getting overly excited about everything the world presents. This causal chain leading to suffering is also called dependent arising or dependent origination (paticca-samuppada). Likewise, when the causal chain of dependent origination is broken, the cessation of suffering is realized.

The Atthakavagga highlights how understanding this dependency leads to liberation, freeing the mind from conflicts and relinquishing desires. It’s comprehending that all experiences—enthusiasm, nonenthusiasm, existence, nonexistence—are conditioned by contact between the self and the world.

To truly fathom the underlying structures enabling our experiences, a shift in our thought process is necessary to contemplate our mind’s dependencies. For instance, when feeling hurt, instead of delving into ill will toward others, we can pause and probe the immediacy of our hurt. Why do we feel this way? Could it be a desire for self-importance? Are there unmet expectations? Who’s responsible for these expectations? This kind of introspection fosters proper attention and mindfulness, delving into the root causes. The more we develop this therapeutic approach to alter our thinking, the more papanca and the perceived separation between “me” and “the world” will be reduced. This journey might lead to the realization that the concept of “I” is not an inherent entity but a construct. With this insight, the desire to control things lessens, reducing both love and hate.

The Atthakavagga states that when one doesn’t regard anything as “mine” and remains unaffected by what isn’t present, true freedom from worldly suffering emerges. This approach leads to the cessation of feelings reliant on contact. Consequently, this realization imparts that assuming a self capable of “controlling” experiences lacks coherence. Experience precedes the assumption of a distinct individual with the power of control. When understood, desires and the pursuit of extremes fade away. Those who are wise refrain from clinging to what they perceive and investigate the dhamma diligently, leading to the dissolution of ignorance. Beyond sensory desires lies freedom from attachments.

This understanding encompasses the truth that permanent ownership is an illusion and separations are inevitable. Completely independent, without comparisons, whether in fear or in grief, still such a person lives in peace.

Regardless of how determined one is to seek peace and order through their concepts, personal preferences often cloud one’s vision, leading to ignorance. Such preferred “realizations” hold little value. The Atthakavagga highlights that pursuing gains—even spiritual ones—tends to breed disputes, disappointment, and troubles among individuals:

“Engaged in dispute in the midst of the assembly wanting praise he becomes anxious. When being refuted he becomes depressed. When blamed he gets irritated and looks for a flaw.” (Att 8:3)

Even in relinquishing certain views, new ones are often adopted, leading to attachment due to following desires:

“Leaving the former, attached to the next, they are always on the move and do not cross attachment. They keep taking up and rejecting like a monkey leaving the old branch as it takes hold of a new one.” (Att 4:4)

And so, rather than picking up new views, it is only through commitment and reflection that we nourish the dhamma.

The Atthakavagga is sometimes perceived as “too difficult” or “too intellectual” by many who attempt to understand it using analytic thinking. However, by embracing more contemplative and introspective practices, exercised in the light of the Buddha’s teachings, one can perceive the Atthakavagga from a different space, getting a glimpse into its profound insight in evaluating the present moment free from preference and preconceived views, liberated from the separation between the self and the world.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.