As the Buddha describes the workings of the mind, a moment of experience builds from the incoming information of sensory input and gradually becomes more complex. The mind is not a preexisting thing but an unfolding interactive process.

When a sense object impinges on a sense organ, an episode of awareness occurs—consciousness emerges as an interaction between the body and its environment. This moment of contact also gives rise to a feeling tone, which is to say the sense object is felt as pleasant, painful, or something in between.

At the same moment the sense object is felt, it is also perceived, which is to say that we interpret what it is in light of past experience, conceptual knowledge, and language. Perception is a form of “making sense” of what we are seeing, hearing, tasting, smelling, touching, or thinking, labeling it in some way so it fits into the story we are always creating and living.

Next, we are likely to “think about” that object and that story. Once we have an image or a word in mind, we can turn that over and reflect upon it. This is where our powers of recognition, association, prediction, and imagination show themselves. These thoughts then serve as further inputs into the system, building upon and interacting with one another to weave the tapestry of a rich inner life.

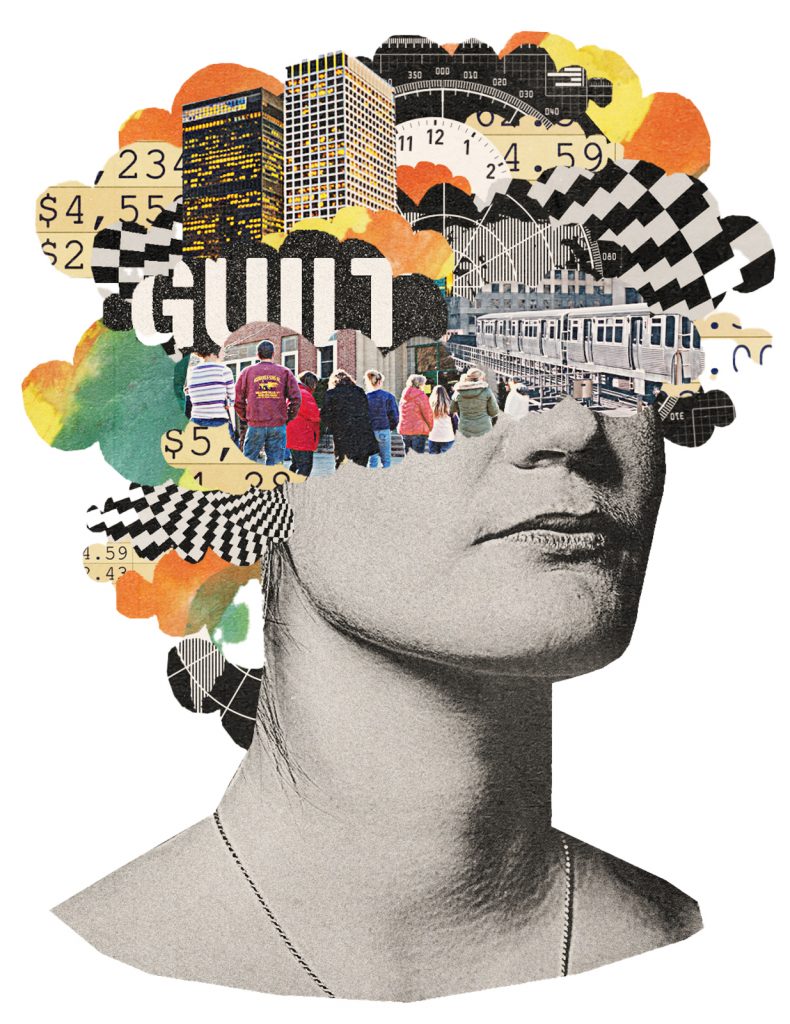

But sometimes this process gets carried away, and this is where papañca comes in. Sometimes the thoughts come in such profusion that it can feel relentless and even overwhelming. Sometimes we just can’t stop thinking about things, or we can’t stop ruminating with the same patterns of thought over and over. This is papañca—perhaps you have experienced it yourself?

The word is based on the idea of something “spreading out,” or proliferating, much as weeds might take over a garden or spilled water might spread out to cover a table. The mind, which at its best can be a powerful tool for examining and understanding the world, becomes an out-of-control train hurtling relentlessly down the track. This affliction seems widespread in the modern world and is both a source and a symptom of much stress, anxiety, and unhappiness.

Papañca can be managed, just as a wild elephant can be tamed. It requires patience, discipline, kindness, understanding, and many of the states of heart and mind that are cultivated with the practice of mindfulness.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.