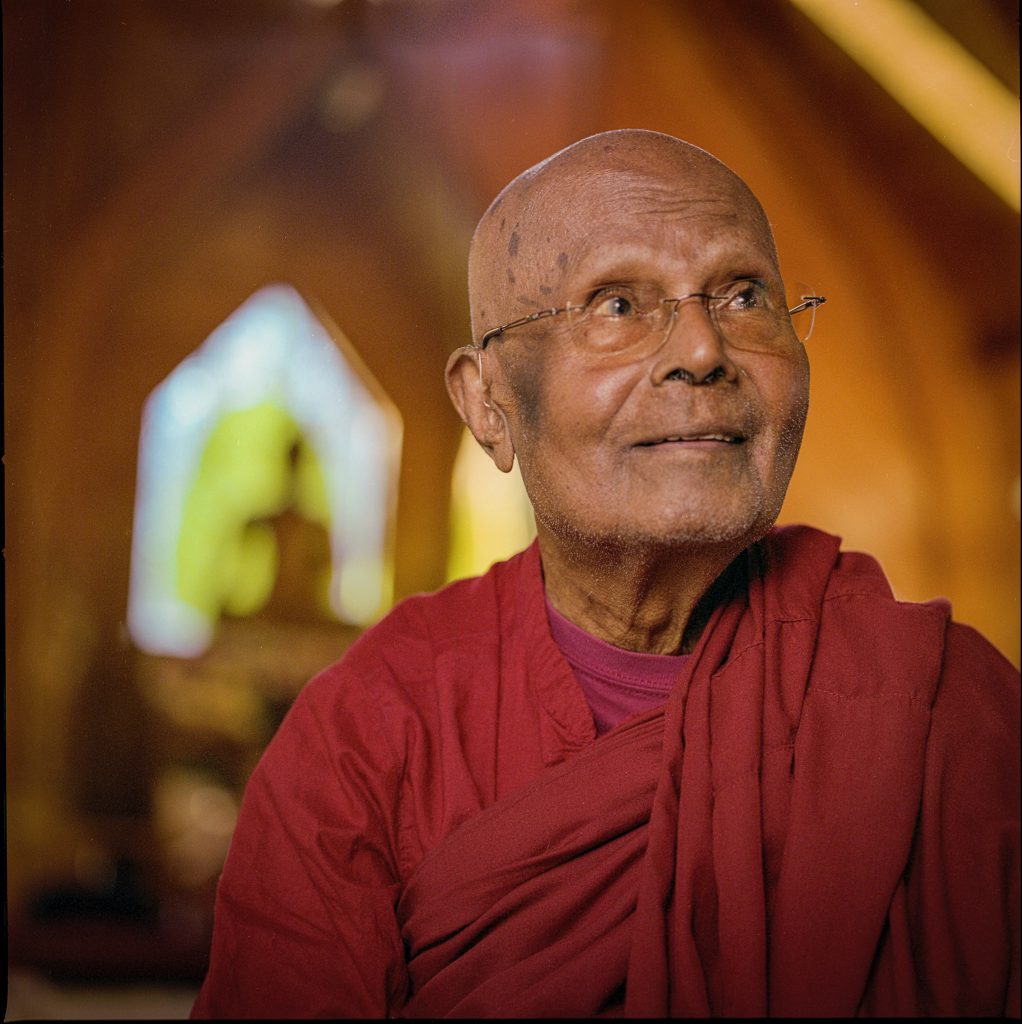

Douglas John Imbrogno is a former longtime member of the Bhavana Society board. He has known Bhante Gunaratana since coming to the Bhavana Society to profile the forest monastery’s opening in the late 1980s. He is editor of the 2020 Wisdom Publications book What Why How: Answers to Your Questions About Buddhism, Meditation, and Living Mindfully, which compiles more than a half-century of Bhante G’s talks and advice. Below are lightly edited remarks he delivered at a celebration of Bhante G’s 96th birthday on Dec. 7, 2023, at the Bhavana Society in High View, West Virginia, that served to mark the release of his forthcoming book, Dependent Origination in Plain English.

I first came to the Bhavana Society in 1989, as a journalist. I was a newspaper feature editor in the capital city of Charleston, West Virginia, and heard of this curious conundrum five hours to the east of me. Deep in the Appalachian hills, a full-on Buddhist monastery had sprung up on a back road in Bible Belt West Virginia. Back then, I possessed only a cursory comprehension of Buddhism and the Buddha’s teaching, although I had long been intrigued by what I understood to be the dhamma’s way of looking at the world.

At the time, I did not know this Pali pronunciation of the more familiar Sanskrit word ‘dharma,’ referring to the body of the Buddha’s teaching. Or that this monastery was of the Theravada Buddhist tradition—‘the Way of the Elders,’ if you look at the etymology of ‘thera’ and ‘vada.’ Or that the forest monastery’s cofounder and abbot was a Theravada Buddhist monk of some renown from Sri Lanka.

When I was growing up, in the latter half of 20th century, in suburban America, perhaps the most likely place you might encounter this word was in the title of the book Dharma Bums, by Jack Kerouac, one of the crown princes of the Beat movement, whose often outlandish, in-your-face antics thumbed a nose at straitlaced society. The Beats were intent on forging another, freer path through life—and your rules, expectations, and conventions stood in the way. Was being a Kerouacian “Dharma Bum” somehow reflective of the spirit of Buddhist behavior and thought?

I myself had grown up Roman Catholic. In my long red cassock and white surplice—very monk-like in retrospect—I served compliantly as an altar boy at possibly the most Catholic-sounding elementary school in all of Ohio: Our Lady of the Rosary. Yet by my early teen years—beset by a questioning mind, an autodidact in the world’s literature, mythology, and faith traditions—I began a long walkabout exit from Catholicism, away from its confounding-to-me tales of virgin births and crucified sons of bearded gods. The inquisitive, flexible mind of the great American Trappist monk Thomas Merton birthed a book that I came upon, Zen and the Birds of Appetite. He boldly drew comparisons and correlations between the monotheism of Christianity and the left-field, godless spiritual approach of Zen Buddhism. For years, I carried that book in my satchel, since it felt like a passport to an appealing distant country, a way of seeing things of the spirit that were as yet half-formed and not yet clear to me.

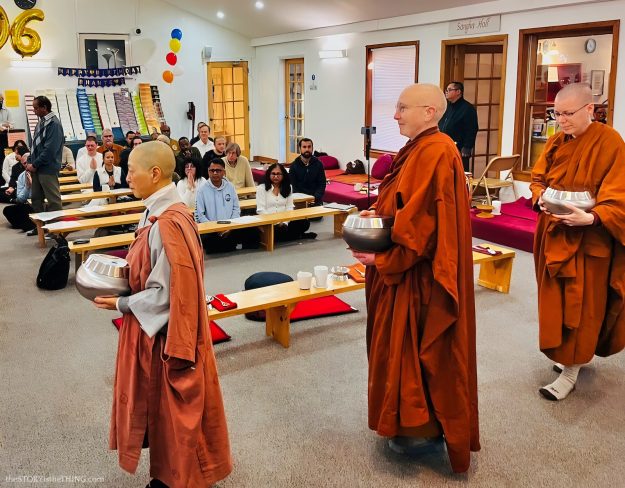

So that was sort of my state of mind and experience when I first showed up in late October 1989, at age 32, with a photographer in tow, for a weekend of interviews and poking around this new, intriguing place. Cofounded in 1985 by Bhante G and Matthew Flickstein, Bhavana had only just opened its doors to the public earlier in the year of my initial visit. There were four monks in residence—Bhante G, Bhante Yogavacara Rahula, Bhante Ananta Bodhi, and Bhante Sona, a 35-year-old Canadian ordained by Bhante G in July of that year, the abbot’s first Bhavana ordination of a bhikkhu, or male monk.

Also in residence was Sister Sama, who had been ordained that July as a samaneri—a novice Buddhist nun—as part of Bhante G’s initial pioneering efforts to revive the order of Theravada bhikkunis, or nuns. I will leave for another day and for someone else an examination of the tale of that fraught, thorny, ultimately frustrated and yet worthy effort—except to note that the order of bhikkunis is growing well today, with Bhante G continuing to encourage its expansion, even as much more needs to be done to equalize the orders of Theravada monks and nuns.

The Build-Out

The ordinations, the study of the Buddha’s teachings in both English and Pali, and the full-throttle construction (directed energetically by Bhante Rahula) spoke to Bhante G’s ambitions for the Bhavana Society. Monks banged hammers and framed walls. Long power cords snaked to chain saws used to clear space in the Appalachian woods for new kutis, or cabins, popping up on the property like mushrooms after a rain. Bhante G was 62 upon our first interview, which is worth noting. After all, by age 60, many layfolk are contemplating which easy chair to collapse into to watch the world pass by as they look forward to blissful retirement.

Of course, the mission of the Bhavana Society is a different sort of bliss, a more lasting kind. Here is how I described this place in the story about the new forest monastery that I wrote after returning home in 1989:

“Under Bhante Gunaratana’s direction, the monks study the Buddha’s teachings and the Pali language, along with frequent sessions of vipassana, or insight meditation. They meditate not to tune out reality, a common Western stereotype. Their aim is to face the ever-changing nature of reality itself, which Buddhists believe is entirely dependent upon the mind. The philosopher Descartes once wrote, ‘I think, therefore I am.’ A Buddhist might say: ‘The way I think is the way I am…”

It is no small matter this word that Bhante G chose to christen this new frontier in Western Buddhism, here at the foot of Great North Mountain along the eastern front of the Allegheny Mountain range. The barest-bones definition of “Bhavana” signifies “mental development.” Yet in preparing to write something for his 96th birthday celebration, I texted Bhante G, asking him for his current favorite explication of this nuanced Pali word. Here is what he texted back—being the thoroughly modern Macintosh and Apple-centric monk that he is, even while being one of the great Early Buddhist Text teachers in the world today: the meaning of ‘Bhavana,’ Bhante G texted, “is the cultivation of mind for the realization of the true nature of everything.”

If you think about it, that definition is as good a shorthand as any for what has been going on in this back-hills monastery and retreat center for nigh on forty years, an ongoing and significant turning of the wheel of dhamma, all kicked into gear by an abbot now marking his 96th year.

The Dependent Domino Effect

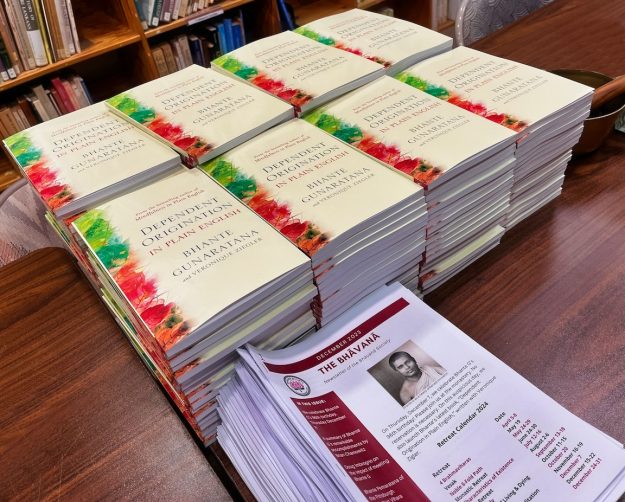

In the intervening years, Bhante G has been a little busy. He has crisscrossed the world teaching. He has inspired, instructed, and guided thousands upon thousands of laypeople, monks, and nuns, in beginning, developing, and deepening their spiritual practice. And he has written a few books. Well, he has written a lot of books. His first widely distributed one, the now classic text Mindfulness in Plain English, has been translated into more than thirty languages. Stop by the Bhavana library to see copies of his books in the host of languages into which they’ve been manifested, gathered for years by librarian Judy Larson.

And on this day, courtesy of his publisher, Wisdom, we celebrate the delivery of advance copies of a book to be released in 2024 on dependent origination, one of the Buddha’s most significant—yet perhaps least understood or discussed—teachings, at least in the world of popular Buddhist discourse. Which is why the book is so important, written by the perfect interlocutor, to lift up a conversation about this consequential teaching.

As for myself—as a founding member of the Stumblebum, Setback, and Pratfall School of lay Buddhist practitioners—I will not attempt in my own words to sketch dependent origination. Instead, I defer to Bhante G’s acuity and keenness of thought. Here are some excerpts from Dependent Origination in Plain English, coproduced and coedited with Veronique Ziegler:

Dependent origination is like a domino effect: everything gradually falls when one link topples. It starts with ignorance, and so with the dissolution of ignorance all the steps of dependent origination leading to sorrow, lamentation, pain, grief, and despair disappear as well. Therefore, understanding ignorance and how to end it irreversibly is the way to live a life free from suffering…

Nothing happens in isolation: when this arises, this arises. But being gripped by ignorance, we are not able to see this. And therefore ignorance is not knowing dependent origination…

We generate our joy and our misery by the way we think. Here again, we find the explicit manifestation of the dependent origination formula in our daily lives…

If we are not skillful enough our mind can make us believe that we are something we are not. Ignorance is very good at deceiving us that way, and if it is powerful enough we will not know that we are being deceived, making it even more difficult for us to escape from this deception… It is possible to spend our entire life deluded by our own mental formations…

Good intention by itself is not enough; it must also be accompanied with wisdom. These intricacies demand our full, mindful attention in order for us to maintain a wholesome state of mind and act skillfully…

Whatever prevents us from cleansing, freeing, and fully liberating our minds must be avoided at all costs…

Suffering does not arise independently. It arises based on certain conditions, and when those conditions are eliminated, it ceases. This, in short, is the teaching of dependent origination, and it leads to the complete elimination of ignorance, the cause of suffering…

As long as ignorance is there, suffering is there. As long as greed, hatred, and delusion are there, suffering is there. If you want to get rid of your suffering, remove greed, hatred, and delusion from your mind…

The general belief during the Buddha’s lifetime, just as today, was that suffering just happened by accident or that it was created by oneself, others, or a combination of these. But dependent origination demonstrates that everything is conditioned, that nothing comes into existence independently, without causes and conditions…

It is a deep, elaborate, and comprehensive teaching that leads us to a profound understanding of ourselves and ultimately a state of absolute inner peace and serenity.

Wise Association

In conclusion, I would like to share one other very important point. The Buddha exhorted us to not associate with the foolish, to always associate with the wise, until the time we attain enlightenment. So it is a good thing indeed to be in this good place and to share the benefits—on the occasion of Bhante G’s 96th birthday—of associating with his good and wise company.

One of my favorite Pali phrases—because of its harmonious lilt and what it signifies—is kalyana mitta, which means a spiritual or admirable friend. Kalyana mittas are not just good buddies. They are essential to our spiritual development. How essential?

The Upaddha Sutta in the Samyutta Nikaya of the Pali canon describes a conversation between the Buddha and his faithful attendant Ananda, who sometimes serves as a foil to make important points in the Pali canon. Ananda wakes up one day, all excited to share with the Buddha a brilliant insight that has flowered in his mind. He corners the Buddha’s attention and enthusiastically declares, “This is half of the holy life, lord: admirable friendship, admirable companionship, admirable camaraderie.”

Now, imagine Ananda’s face as the Great Teacher says: “No, you’ve got that wrong, man!” And then proceeds to tell him never to utter such words. As the sutta continues, the Buddha responds: “Don’t say that, Ananda. Don’t say that. Admirable friendship, admirable companionship, admirable camaraderie is actually the whole of the holy life. When a monk has admirable people as friends, companions, and comrades, he can be expected to develop and pursue the Noble Eightfold Path…”

The Buddha is, thus, a kalyana mitta, pointing to the Way we must then follow ourselves—it’s the only way it can be followed. For many of us in this room and across the world, Bhante G has for so long been our great kalyana mitta. And may we pass it forward and be kalyana mittas to our friends, companions, and compatriots along the Way.

Since I have been blabbing for a bit, let us now take a moment of silence, taking in a deep breath… Here, then, is a final reminder, one you will hear from Bhante G’s lips when he concludes morning meditations in this very room:

There is no concentration without wisdom,

No wisdom without concentration.

One who has both wisdom and concentration

is close to peace and emancipation.

And, so, let us dedicate our efforts this day and throughout however many days we have left to us in this life to emulate the example of the life of Bhante Henepola Gunaratana Mahathera. To work for our own liberation and the liberation of all beings. I conclude with an excerpt of a loving-friendliness meditation you may also hear coming from Bhante G’s lips:

May the fearstruck be free from fear,

May the grieving be free from grief,

May the suffering be free from suffering.

So, too, may all beings be.

From the highest realms of existence to the lowest,

may all beings arisen in these realms,

with form and without form,

visible or invisible,

born or coming to birth,

be released from all suffering

and attain to perfect peace.Sadhu, Sadhu, Sadhu!

Dependent Origination in Plain English by Bhante Gunaratana is available starting June 11, 2024, from Wisdom Publications. Excerpts from the book used with permission of Wisdom. For more, consider enrolling in Wisdom’s recent offering, “Mindfulness in Plain English: An online course with Bhante Gunaratana.” Visit https://wisdomexperience.org for more information.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.