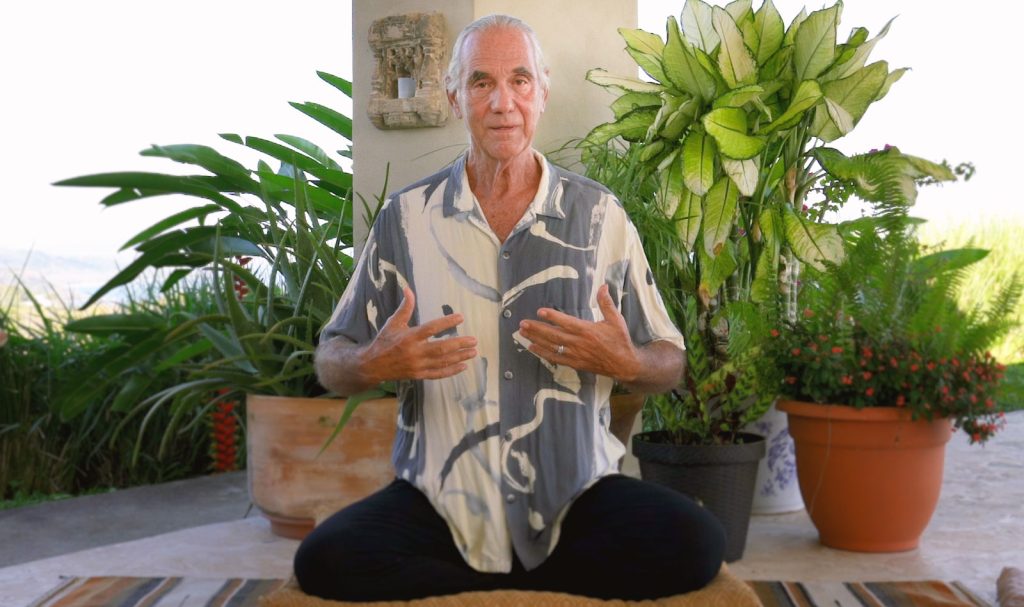

In reflecting on how my practice has evolved over the years, I look back over my life and remember quite vividly the first Buddhist retreat I ever attended almost exactly fifty years ago. It was taught by a wonderful Thai monk, Koon Kum Heng, who presented a classical Theravada practice that he called rising and falling. For seven long days I did nothing but observe how my breath caused my front belly wall to rise and fall on the inhalation and exhalation. With each inhalation the belly could be observed, and eventually be felt, expanding outward. On the ensuing exhalation it would contract back in. The movement never stopped. Over and over and over again while sitting in an upright meditation posture, standing, lying down, and walking slowly from place to place, I did my best to focus my entire attention on my belly as it rose and fell on the breath.

Such simple instructions, but like everything that first appears simple, it was far easier said than done as inevitably I’d find that my mind would wander off on a parade of errant thoughts that with uncanny success would hijack my awareness and leave me oblivious to the rising and falling of my belly. The practice only became somewhat stabilized toward the end of the retreat when I realized I was no longer observing the rising and falling action from the safe distance of my mind but was actually feeling the expansion and retraction of the belly and grounding myself there.

At one point during that retreat I recall chuckling to myself over a reminiscence about a phrase that would not infrequently come up in conversations with friends of my parents. Oriented toward succeeding in life (which to them mostly meant going into medicine, law, or business), they would often remark when I told them as a teenager that I had absolutely no idea what I wanted to do with my life: “Well, you’re not going to just sit around and contemplate your navel, are you?”

During the retreat I realized that they really had no idea about the source from which that phrase—which they viewed pejoratively—had arisen. To them it meant not committing to anything and wasting away your life. Yet here I was, hour after hour, day after day, doing nothing but “contemplating my navel,” and I loved it! By the end of the retreat I felt that my center of gravity had dropped down out of the thoughts in my head into the felt presence in my belly. Thought would appear and evaporate so effortlessly that I had my first clear awareness that I was not my thoughts. I was not the mind that thinks and the speaker of those thoughts. Instead, I was the grounded feeling of presence emanating out of my belly. It felt so relieving and wholesome. Endlessly rising and falling, rising and falling, and I loved going along for the ride.

Only many years later did I understand that this practice of observing the rising and falling of the belly in response to the breath draws on the opening instructions on breathing as recorded in the Satipatthana Sutta, one of Buddhism’s earliest texts whose words have been attributed by some scholars to the Buddha himself. After telling us to sit down in a posture of meditation with the spine erect and upright, he instructs us to become aware of the breath as it enters and leaves the body, and he goes on to tell us to conduct this examination at the front of the body.

Throughout the long history of Buddhism, the two most popular places at the front of the body to explore these instructions have been the nostrils, where breath can be felt to go in and out, and the front belly wall that can be felt to rise and fall unceasingly in response to the breath. Constant observation of the breath can be so potent and effective that many Buddhist traditions understandably focus exclusively on this opening instruction. But this is not where the instructions end. Just a few short sentences later, in a completely remarkable statement, the Buddha suggests that we no longer just focus our awareness narrowly on one small place at the front of the body but instead breathe through the whole body.

I’ve wrestled and danced and struggled and played with that culminating instruction for the better part of my life on the cushion. What could it possibly be pointing to? Over the long years I’ve come to realize that the initial instruction to become aware of breath at the front of the body refers to the classical practice of mindfulness but that the culminating instruction to breathe through the whole body takes us into the world of bodyfullness.

What might rising and falling mean to the exploration of bodyfullness?

To breathe through the whole body you have to do two things. First, you need to awaken the felt, shimmering presence of the entire body. How could you breathe through the whole body if you’re unable to feel it? On every part of the body, down to the smallest cell, minute, tingling, buzzing, carbonating, pulsating sensations can be felt to exist. But, deep in our own thoughts, we have little awareness of their vibratory presence. In fact, we have to blanket them over to be able to function in the quality of consciousness that passes as normal in the world that is so often, as Thich Nhat Hanh famously observed, lost in thought. Experiencing the entire body, from toe to head and everywhere in between, as a unified field of felt vibratory presence, is the first step in the awakening of a bodyfullness that can experience breath interacting with the whole of the body.

The second requirement—and this is the most radical piece I bring to the dharma conversation—is that we need to allow subtle, continuous, amoeba-like motions to occur throughout the entire body in resilient response to the force of the breath that wants to make its transmitted way through a relaxed and awakened body—not unlike how a wave moves through a body of water. In most presentations of meditation, we’re instructed to sit completely still, like a stone garden statue of the Buddha. But this frozen stillness not only doesn’t allow the breath to move through the body, but it also causes so many of us so much pain and discomfort in long retreat.

Over the decades, as my awareness expanded naturally from an exclusive observational focus on my belly to an inclusive felt awareness of the whole of the body, I’ve come to realize that these altogether natural motions in my body start with giving my entire spine permission to rise and fall on the breath. The joints in the spine are no different from joints anywhere in the body. They’re there for one purpose and one purpose only: to move. In a deeply relaxed state I can feel my entire spine lengthening as I inhale and shortening back down as I exhale. In other words, I can feel the entire spine rising and falling. What I’ve found over all these long years of fascination with sitting down on my cushions is that, when I enter into bodyfullness and experience how breath can be felt to interact with, stimulate, and move through the whole body, a plug gets pulled on the consciousness of “lost in thought,” and the altogether natural dimensions of awakened body and mind, which “lost in thought” keeps us forever removed from, are revealed effortlessly and spontaneously.

***

sit down in a posture of meditation

just feel yourself sitting there

as tall as you can be

but as relaxed as you can be

focus your attention

on your belly

even in the stillest of bodies

your belly can be observed and felt

to rise and fall

expand and contract

on the inhalation and exhalation of breath

rising and falling

rising and falling

observe the motions

feel the motions

become the motions

***

now broaden your focus

to include a felt awareness

of your entire body

leaving nothing out

pass your awareness

slowly through your body

from head to foot

awakening felt shimmer

through the simple act

of focusing your attention

on a part of the body

like shining a flashlight

into a dark corner of a basement

***

relax as you inhale

and feel your entire spine lengthen

your lumbar spine moves and lengthens

your thoracic spine moves and lengthens

your cervical spine moves and lengthens

as you exhale

feel the entire body shorten back down

inhale fully and deeply

down from your diaphragm

down through your pelvis and legs

into the earth

simultaneously

feel how the breath can be felt

to lift the entire body upward

rising and falling

through the entire long shaft

of the upright body

***

breathing down into the earth

grounds and stabilizes clarity of mind

as it initiates the rise

stay grounded in the earth

when you feel the breath

causing the head to lift

let go and soften

the top of the head

the muscles around the eyes

and both sides of the cranium

feel the energies

in these three places in the cranium

billowing open

let vision and sound

replace thought

explore the rising and falling practice of bodyfullness

while you’re sitting formally in meditation

while you’re standing and walking

and making your way through your life

◆

Try Will Johnson’s Tricycle online course, “The Posture of Meditation,” at learn.tricycle.org.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.